Broadway Choreographers Bring New Shows to the Stage

It’s mad-dash time on Broadway, as shows scramble to qualify for the June 11 Tony Awards. “It is a crazy season,” says Andy Blankenbuehler, who won last year for choreographing Hamilton. And the 10 musicals arriving in the two months preceding the deadline, April 27, “are all over the map,” he says. “So many different audiences will find a show to really be in love with.”

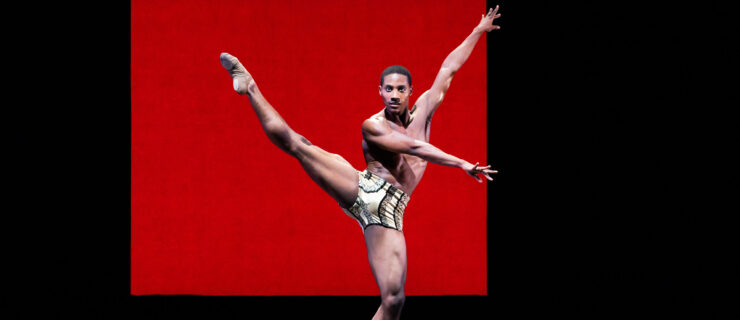

One of them is his own, Bandstand, set in 1945 as GIs resume their lives after World War II. Working with composer Richard Oberacker and writer Robert Taylor, “Andy the Director” focused initially on “music, text, characters—establishing the world,” he says, to tell the story of veterans forming a big band.

Bandstand

Photo by Jerry Dalia

With a well-received production in 2015 in New Jersey, “we found our way,” he says. “Since then, Andy the Choreographer has taken over.” He estimates that there’s now twice as much movement, split between the jitterbugging spirit of the era’s music and “the whole other physicality” of soldiers at war.

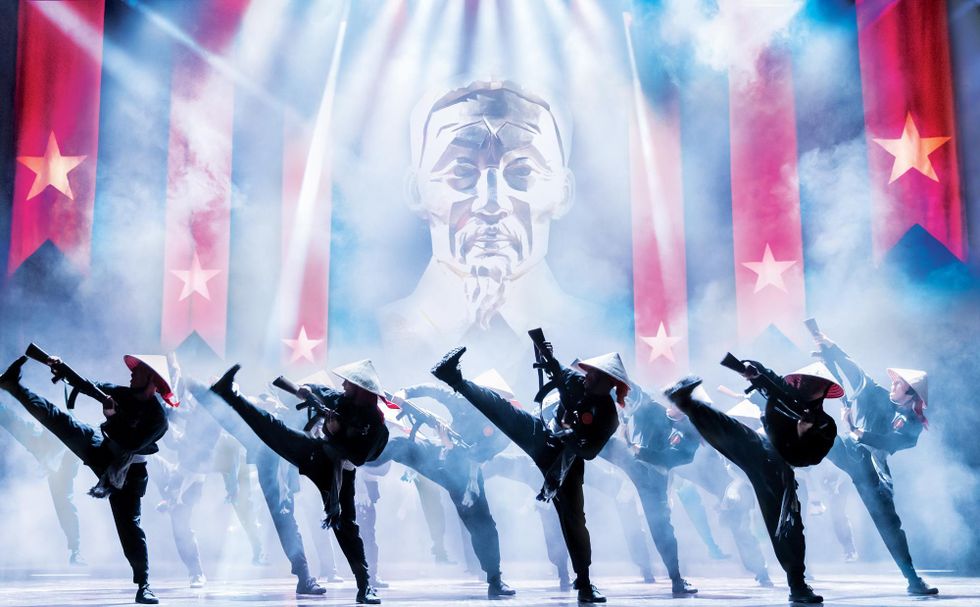

A later generation of GIs drill in Miss Saigon, the revival of the 1991 hit that transposed the story of Madama Butterfly to the Vietnam War era. There was so little dance in the original that Bob Avian was credited with musical staging rather than choreography. “But,” Avian says, “I’ve been doing it for 27 years, and I’ve kept introducing more choreography.”

Miss Saigon

Photo by Michael Le Poer Trench and Matthew Murphy

There are now four full-out dance sequences for the 30-member ensemble, which this time was cast with “people who could dance as well as sing.” There are other changes too, he says: “A darker, grittier feel,” appropriate for a musical about “the only war America ever lost.”

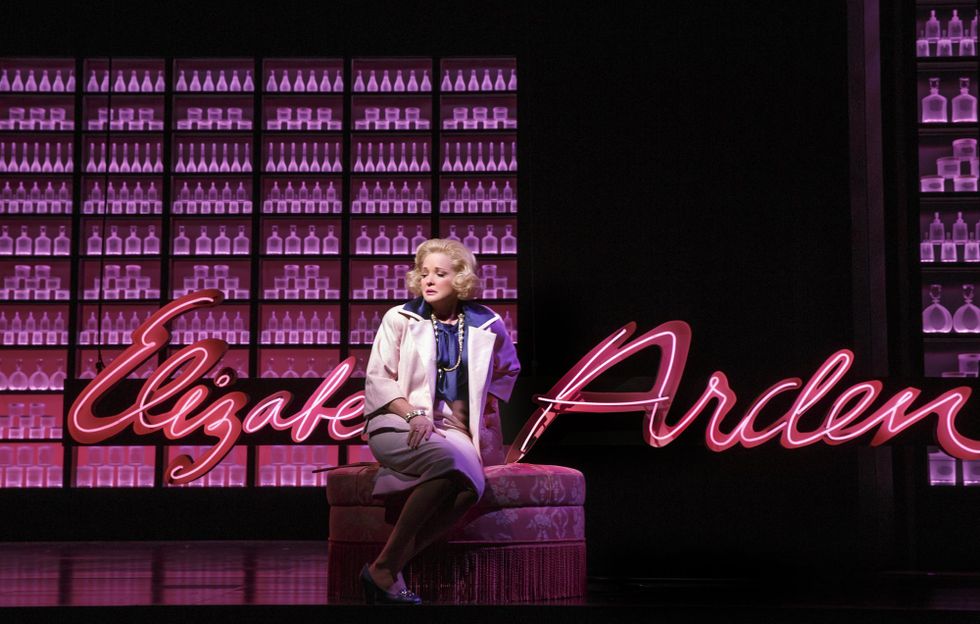

In War Paint, which Christopher Gattelli is choreographing, the generals are the 20th-century cosmetics tycoons Helena Rubinstein (Patti LuPone) and Elizabeth Arden (Christine Ebersole). Tracking their cutthroat rivalry from the ’30s to the ’60s, War Paint allows Gattelli to play with multiple dance genres.

War Paint

Photo by Joan Marcus

It also gives him a chance, after the testosterone-happy South Pacific and Newsies, to choreograph for all-female ensembles. His “Arden girls” are tall and fresh-faced, the Rubinstein women older and earthier. With its barrier-busting heroines—both, as it happens, immigrants—the show “couldn’t come at a better time,” Gattelli notes. And he loves that “you can’t believe it really happened.”

Another incredible-but-true story informs Indecent, the off-Broadway hit with choreography by David Dorfman. Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Paula Vogel and director Rebecca Taichman based it on the scandal that erupted when a play with a lesbian love scene opened on Broadway in 1923 and landed the cast in jail.

Indecent

Photo by Carol Rosegg

Studded with vibrant, klezmer-style songs that gave the postmodernist an opportunity he welcomed to “move out of the completely abstract realm,” Indecent mixes theater history, sex and politics with a ghostly ambiance that prefigures the Holocaust. “It’s not a traditional musical,” Dorfman says, “where the songs are designed to tell a particular story. But the songs and movement are crucial to keeping the feeling.”

Another historical tragedy looms over Come From Away, choreographed by Kelly Devine. In Newfoundland, a come-from-away is a stranger, and on September 11, 2001, the town of Gander, population 11,000, was inundated with 6,700 come-from-aways as its airport became the unintended destination for 38 planes grounded by the terrorist attacks.

Devine says it took “trial and error and a lot of investigating to find the right tone and the right amount of movement.” And she found it a bit unnerving to design choreography based on people she’d actually met. Apart from some Celtic folk dancing in a bar, there are no actual dance steps.

Come From Away

Photo by Matthew Murphy

Two other musicals are similarly constrained. To be true to the story of Groundhog Day, Peter Darling and co-choreographer Ellen Kane had to design movement for ordinary people in an ordinary place (if you call Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, ordinary); in Amélie, but people have told him, “Omigod, the entire show was choreographed!” while others says, “There was no choreography!”

From Kane’s description, Groundhog Day could provoke much the same reaction. “The show is fully staged, with a huge amount of movement,” she says, “but it’s based a lot on naturalism.” Its single “dance dance,” a tap number, “isn’t about fancy steps,” but about the time warps created by overlapping rhythms.

Groundhog Day

Photo by Manuel Harlan

Time warps are the heart of Groundhog Day, based on the 1993 movie that starred Bill Murray as a TV weatherman reliving a single day, and Kane, who’s previously worked with Darling as an associate, says her “mathematical mind” is particularly suited to the demands of the show’s repeating choreography on five stage revolves.

By contrast, two other musicals rooted in movies, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, choreographed by Joshua Bergasse and Anastasia, choreographed by Peggy Hickey, are all-out dance shows. Based on the 1997 animation, Anastasia boasts eight dancers, “six singers who move well,” and production numbers that include “a grand Russian ball” and a ballet, “a full-on Swan Lake thing,” Hickey says.

Anastasia

Photo by Joan Marcus

Hello Dolly!

lacks both a ballet and an Imperial ball, but the 1964 classic has plenty of dancing, as noted by Amélie‘s Pinkleton. “We’re not doing Hello, Dolly!” he says. Then he adds, “God bless those that are”—Warren Carlyle got the job—”’cause I can’t wait to see it.”