Man of the Moment: Kyle Abraham

Choreographer Kyle Abraham’s works are freighted with heavy social questions, tackling issues like race, gender, isolation and community. But what might be most intriguing is his physical vocabulary. As both a choreographer and a performer himself, Abraham fuses the rippled posturing of hip hop with the curves and weight of modern dance. A stutter pulses through two men’s bodies as they negotiate their approach; the adjustment of a hand position gives a shoulder roll a streetwise edge.

“Watching him in the studio, it’s like watching an artist doing sketches; you can’t tell where a movement begins and where it ends,” says Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater artistic director Robert Battle. When he commissioned Abraham to create Another Night for the company in 2012, he explains, “everyone was learning a new language.”

In the last two years, it seems, the 36-year-old dancer and choreographer has suddenly landed in the spotlight. Abraham’s strong social messages and hybrid style have made him the darling of the dance world establishment—gaining him honors from Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, commissions from Alvin Ailey and New York Live Arts, and a prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, often referred to as a “genius grant.”

The recent attention has been a game changer: This winter alone, he worked on a set of new works for NYLA, a solo that premiered in Lyon, France, and a video side project, while also preparing new members of his company for tours of Pavement and The Radio Show—all before heading abroad to perform a duet with Wendy Whelan this summer.

Now, everyone is asking: What will Kyle Abraham do next?

Above: In

Pavement, Abraham uses the setting of a basketball court as a backdrop to dig into issues like black masculinity and police violence. Photo by Carrie Schneider, Courtesy A.I.M.

Late Start

Abraham’s diverse set of influences—which range from Martha Graham to hip hop and rave culture—may owe something to the fact that he didn’t begin dance training until his senior year in high school, after being cast in a school musical. He immediately started taking some classes at Pittsburgh’s Civic Light Opera Academy, as well as at the Creative and Performing Arts High School. “All the teachers were so encouraging,” he says. While Abraham played catch-up with technique, “they would bring me in tapes to watch—Garth Fagan, Ulysses Dove.”

He says now that late start actually helped determine his path. “Because I came to it so late, I always thought I was going to be a choreographer.” He went on to study at SUNY Purchase, where there were two separate composition classes at any time—so he would do his own class assignments, then ask about the other class’s tasks and do those on his own.

“From the get-go, he made solos for himself that showed something special about him as a dancer,” says Neil Greenberg, a former choreography professor at Purchase. “He’s really successful at stripping away the aspects of the modern dance vernacular that get in the way for him, but without taking away everything.”

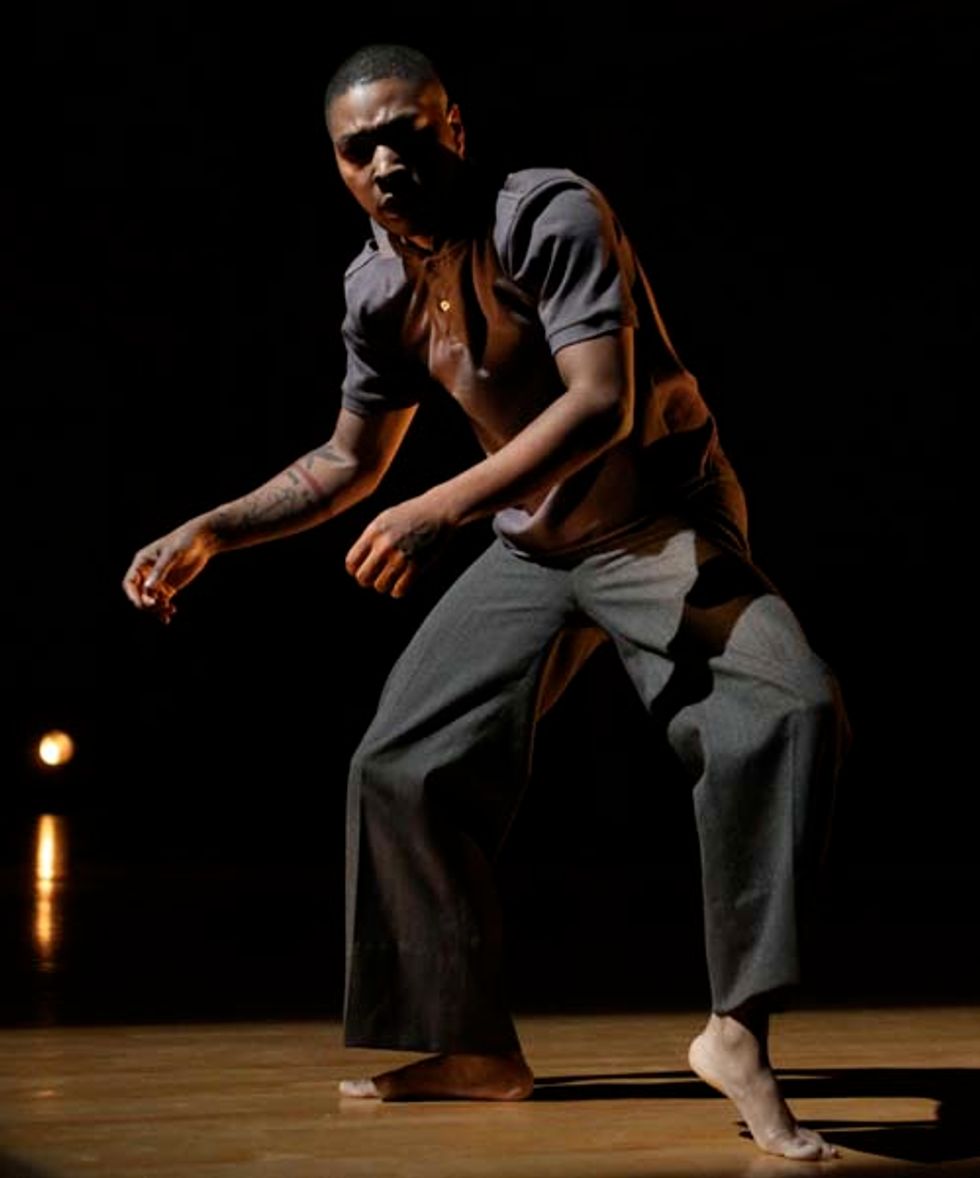

Right: Abraham in

The Radio Show. Photo by Steven Schreiber, Courtesy A.I.M.

Finding an artistic home after graduation, however, proved challenging. Abraham quickly got a position with Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane—one of the companies that had inspired him in high school—but “that did not work out well,” Abraham says. “You don’t learn in college about company dynamics. I was like: Wait, I can’t just do my own thing?”

He was fired within the year. “I realized years later that I didn’t really want to be a dancer in the company; I just wanted to be around those people.” Even Jones—now executive artistic director of NYLA and a big supporter of Abraham’s work—concedes that he didn’t notice the young dancer’s talent. “I had a room full of personalities,” he says. “I told him later that I wasn’t really seeing him at that time.”

Back in Pittsburgh, Abraham’s father was showing early signs of Alzheimer’s. So he took time off, moving home for a while, and then wandering to London and San Francisco, working in retail, considering other paths.

But by 2004, he was ready to give dance another try and entered the MFA program at New York University. “The first year was a struggle,” he admits, “but I was making work. There were really talented dancers that I got to work with.” During the summer program there, he caught the eye of choreographer David Dorfman, who later asked him to join his namesake company. “I loved that company,” Abraham says. “There were times I forgot we got paid.”

Residencies and Grants

Meanwhile, his own work was getting noticed, as well.

Abraham began making solo appearances at DanceNow NYC and Harlem Stage while still at NYU; by the time he appeared at the White Wave Festival in 2005, he had a name for what was then a one-man company: Kyle Abraham/Abraham.In.Motion.

A jaw-dropping solo piece, Inventing Pookie Jenkins—featuring Abraham, shirtless, in a flowing maxi-skirt—landed him a slot at New York’s Fall for Dance showcase. “I remember seeing this young guy, wearing a long, white skirt, moving in the most seductive and beguiling way,” says Jones, who saw a kindred spirit in the younger man. “It felt like an idea I would have done in my time and in my way. I thought: Look at the time we’re in right now, that he can be onstage and move that way.”

Connections back in Pittsburgh helped Abraham find funding to develop work there; later support from the Joyce Theater Foundation in New York allowed him to bring in administrative help and an editing advisor—ultimately helping Abraham create The Radio Show, a 2010 Bessie Award–winning piece.

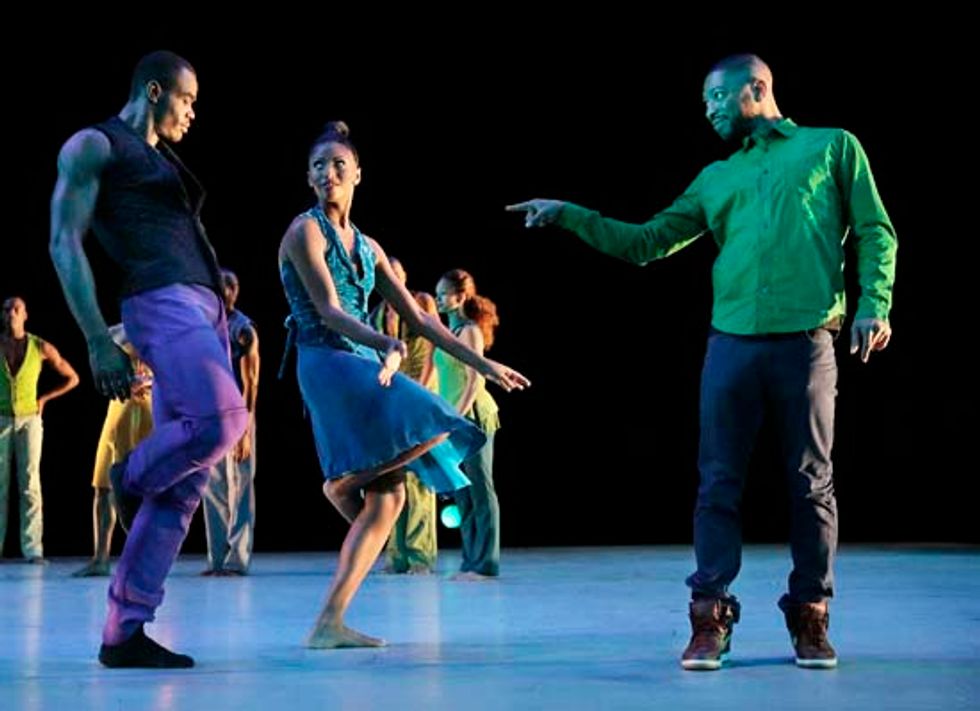

Above: Abraham and A.I.M. dancer Chalvar Monteiro in

Live! The Realest MC. Photo by Steven Schreiber, Courtesy A.I.M.

Then, in one breakout year, 2012, Abraham hit the big time: He was named the 2012–14 resident commissioned artist at NYLA; he also received the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Award, as well as the Ailey commission and a $50,000 grant from United States Artists. Just a few years earlier, Abraham was taking food stamps to get by; now he left Dorfman to focus on his own company; soon after, he received the prestigious MacArthur nod, worth $625,000 over a five-year period.

Creating Work

In conversation, Abraham is thoughtful and culturally omnivorous. At one point, he mentions James Baldwin as an influence—then dismisses him as too obvious. Back in high school, he recalls, he resisted full-time enrollment at the performing arts school because the academics were stronger at his own school. His musical tastes include classic jazz and pop, but also contemporary classical star Nico Muhly.

Those influences weave their way into his dances. The Radio Show looks at communication breakdowns—the demise of urban radio and his father’s aphasia and Alzheimer’s—while both Live! The Realest MC and Pavement deal with cultural notions of masculinity for black men. To create work, he immerses himself in a piece’s concept—reading Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns, about the Great Migration, in the warm-up to Pavement, and studying up on the civil-rights movement (and listening to music of the era) for a new work dealing with the 1960s.

New Award, New Pressure

Abraham admits there’s a flip side to the flurry of attention. As generous as the MacArthur grant is, it also puts a new level of pressure on a company still operating like a startup, with a slender checking account, no board and no individual donor base. “My dancers still need money; I still live in a studio apartment—in a basement.” And although he’s now able to pay for health insurance for his company, he points out, “I still have dancers who want to leave to go dance somewhere else. I still have to strive to be that choreographer who dancers want to spend their career with.”

Above: Abraham directs Ailey dancers Jamar Roberts and Jacqueline Green. Photo by Paul Kolnik, Courtesy Ailey

.

However, Abraham now has dance world luminaries lining up to support him. At Ailey, Battle speaks hopefully of future commissions; Jones, meanwhile, expresses hope that he can pass along to Abraham some of the help he himself received as a young choreographer. “This is an exhilarating time for him—but this is a treacherous time for him,” Jones says. “Everybody wants a piece.”

Even more challenging for Abraham himself, perhaps, is the expectations the MacArthur honor confers on its recipients.

“The scary thing for me is thinking about the weight of the award,” Abraham says. “It sets up an expectation that the work will always be great. There’s no guarantee.”

Rachel F. Elson is a New York City-based writer.