When You Literally Want To Pull Your Hair Out

I first started pulling out my eyelashes when I was 9, after removing fake ones at a dance competition. A few of my own eyelashes came out and I felt a new sensation. It hurt, but the prick also felt so good.

Eventually, I was pulling even when I was not wearing stage makeup, sometimes unaware of what I was even doing. It happened while I was reading or doing homework, or when I was sad or angry.

For the next five years, I secretly pulled my eyelashes, then moved to my eyebrows and eventually the back of my scalp. Finally, at 14, I told my mom what I had been doing and she took me to see a child psychologist. It turned out I had trichotillomania (a.k.a. “trich”), which is one of a group of behaviors known as Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors in which people repeatedly pull, pick, scrape or bite their hair, skin or nails.

My mom reassured me that I was going to be okay, that everyone had their “something” to endure and this just might be mine. With the therapy and a supportive family, over next few years I was not pulling as frequently.

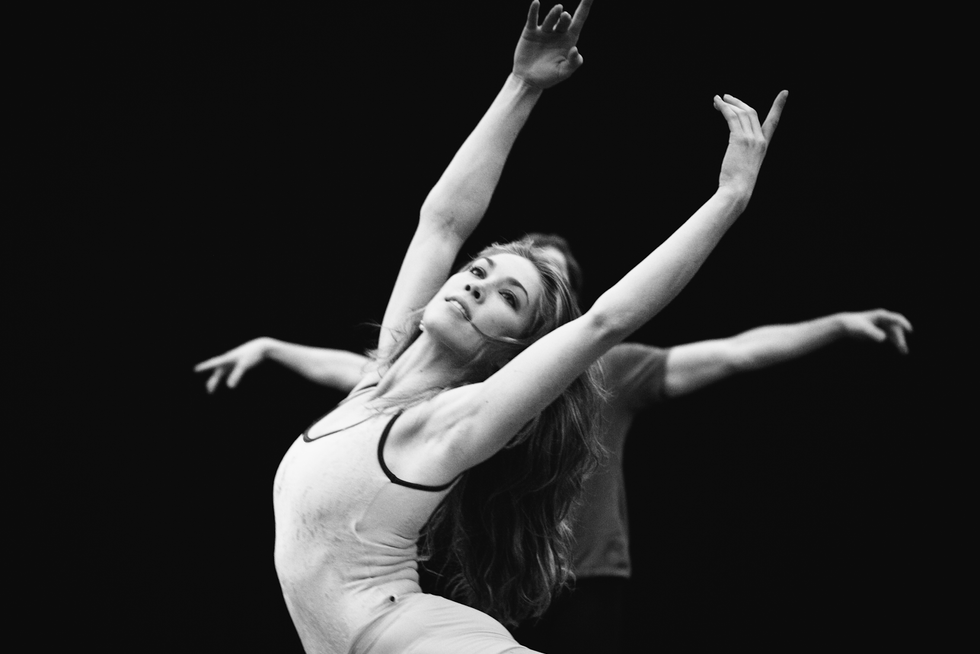

Anthony Matula, courtesy Meister

Then I graduated from high school and joined Nashville Ballet’s second company. And in my second season with NB2, the repetitive pulling started again on a regular basis. I have struggled with it ever since.

My disorder affects me every day. I’ve spent years ashamed and embarrassed by the bald patch at the back of my head. My vanity, fortunately, has helped me avoid pulling in the more obvious places I did as a child.

But every day I take precautions to hide my “spot.” I typically wear my hair in a high bun or twist when in the studio. Every once in a while I will wear it low to see if I can force myself not to pick.

Repertoire that requires my hair to be down or partially down causes its own special stress. I spend time coloring in the spot with brown eyeshadow, hoping no one can see it from the audience. I remember a specific performance in which my hair was down and teased. I spent a large chunk of the show thinking someone might notice my missing hair. I do not know which was worse—the fear of being discovered or the regret I felt afterward for not fully committing to my character or enjoying the opportunity to dance.

Competing at Varna International Ballet Competition. Photo courtesy Meister.

During my first years in the company I only told my two roommates about my trich. Over time I expanded the circle of people I chose to tell, with most of the company now aware of my challenge.

Recently, I opened up to my artistic director about my disorder. I had been with the company for eight years and for the first time I felt I needed, and was ready, to share my struggles with him. I had always viewed the trichotillomania as a weakness of character, something that might hold my career back. Just as I had heard so many years earlier, he said everyone has their “something” and wanted to make sure I had the necessary support.

As I talk more openly about dealing with trichotillomania, its power over me has decreased but not entirely gone away. I still pull when I’m anxious and upset, or mindlessly pluck when I’m driving or standing in the back of a rehearsal. Pulling the “right” hair (coarse and dark) still leaves a tingling sensation on my head and a strange satisfaction that I plucked a good one. But this satisfaction quickly causes anxiety that I don’t have the self-discipline to make myself stop pulling altogether. Self-discipline, a skill I have perfected as a professional dancer, somehow cannot help me in this area of my life.

Nicholas Scheuer and Alexandra Meister. Photo by Anthony Matula, Courtesy Meister.

As I continue to come to terms with my trichotillomania, I’ve learned that we are all flawed humans. This part of me has shaped who I am, but it does not define me. It has allowed me to understand sadness, shame and pain, giving me the ability to express myself through my work.

I hope that by speaking out about my experience, someone secretly dealing with trichotillomania, or another Body-Focused Repetitive Behavior, realizes that they are not alone. I hope they realize that opening up to someone about their struggle can free them not only in their daily lives, but also in their dancing.