Rant & Rave: Don't We Count?

As a former dancer with the Merce Cunningham Company, I have had wonderful opportunities to teach technique and other courses in many schools, companies, and institutes. During the last few years, I have spoken with colleagues across the country about the changing roles for those of us who emerged from the dance profession into higher-education teaching. We have noticed that more often than not, the technique courses we typically taught are being assigned to younger teachers who have multiple degrees and no professional experience. Because of their “credentials,” they are considered by school administrators to be more qualified than those of us who have paid our dues through years of spilling our guts across the world’s stages, releasing ourselves to the works of great choreographers, and who still teach from a fire inside. We find ourselves reassigned to general education technique and theory courses, working primarily with non-dance majors. This is disheartening. Not only can we still dance, but we bring to a program decades of experience performing, choreographing, designing curricula. In some cases, we are the faculty who actually built the dance programs from which we are now demoted.

When I reflect upon the teachers who trained me over the years, I have to say the ones who taught the best classes were those who were older and had been in the profession. What I learned from teachers such as Merce, Mary Anthony, Hector Zaraspe, Anna Sokolow, Edward Caton, and Mia Slavenska was the basis of my work ethic—how to structure my life as a dancer around the constant training, for it is never complete. A dancer doesn’t receive degrees for attending hundreds of ballet classes, rehearsing dozens of pieces, or performing around the world. The continual grind of alternating excitement and hardship becomes the real education, the glue that holds one together when teaching finally becomes one’s life path after performing.

In contrast, the younger teachers I studied with tended to deliver less balanced classes, favoring combinations in which they personally excelled. I soon learned loyalty to teachers who were interested in helping me become a better dancer. I never thought the younger teachers had more energy or demonstrated better, but rather had an energy that appeared self-promoting. The older teachers placed their focus on actual teaching and demonstrated just enough for the students to understand the combinations. In some cases, the ballet teachers didn’t demonstrate at all, but rather dictated the exercises, focusing on providing pertinent corrections.

Just before Merce passed away in July, I was in New York reconstructing two of his pieces in the studio, and would arrive early to watch him teach company class. Although he was 90 and in a wheelchair, he was still able to teach a brilliant class through the exactness of his verbal explanations. This class was no less challenging than those I remembered from his teaching during the 1970s. (If anything, it was more difficult!)

So what did I gain from all those years of touring with Merce that could possibly benefit the aspiring university dancer? Certainly, learning a large repertory, coping with injuries and illnesses, the realities of touring abroad, performing in challenging venues, taking care of oneself in order to always be able to do the work, and what it meant to commit oneself to a great innovator’s choreography, were vital pieces of career information. I also learned coping skills through Merce’s willingness to explore the field of all possibilities in any situation. Dancing with Merce gave me not only enormous insight into the dance world but an introduction to great artists, musicians, and thinkers because of the company’s multi-disciplinary collaborations. As dancers, we hung out with Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, David Tudor, Buckminster Fuller, and Marshall McLuhan. This became part of the history I lived, digested, metabolized, and am able to share with students.

Although my present situation is an ego-buster, I am mainly resentful because of the age discrimination, degree-discrimination, and the ensuing lost opportunities that I face every day. Can a mega-degreed faculty member who has never had a dance career match a professional dancer with years of first-hand experience? Obviously, I think not, but I am at odds with the decision makers of higher ed. The biggest losers, however, are not the professionals such as myself, but the students. As a friend of mine would say: “This is a crime!”

Sandra Neels, an associate professor of dance at Winthrop University, performed with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1963–1973 and has been staging his work since 2002.

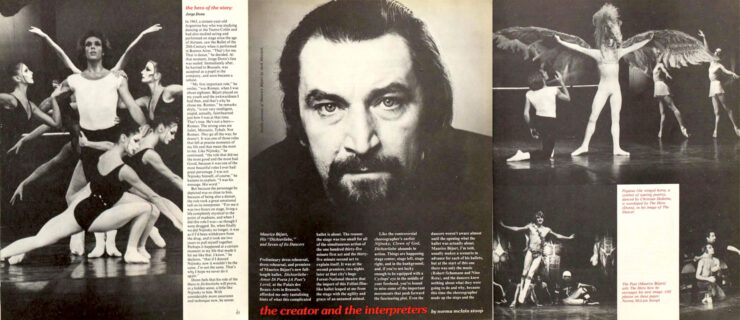

Photo of Hector Zaraspe teaching at Juilliard in 1978-1979 by Peter Schaaf, courtesy Juilliard