Should Artists Respond to Reviews?

We all know the internet has overhauled traditional dance criticism, giving anyone with an opinion and a wifi connection the ability to share their thoughts, no matter how informed—or not—those thoughts might be.

But should those who take part in a ballet have their say as well?

Last week, writer Hanna Weibye reviewed a Royal Ballet triple bill on theartsdesk.com, a British arts journalism website. She had a particularly severe write-up of David Dawson’s The Human Seasons:

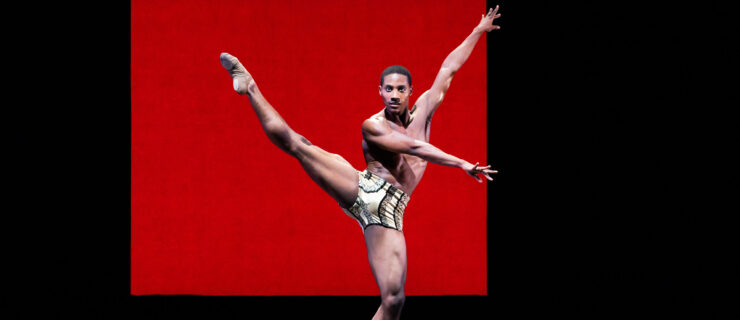

“The less said about David Dawson’s The Human Seasons, the better. In fact, I’d recommend missing it entirely. Everything that is vapid and dreadful about contemporary ballet is present and correct: repetitive score based on arpeggios and ground bass; greige set with abstract light projections; complicated but banal “neo-classical” choreography that even Royal Ballet principals struggle to display to advantage; and startling and tasteless gymnastic feats. It may be testimony to Sarah Lamb’s beauty and strength that she manages to make being swung around by one knee look elegant, but she shouldn’t have to endure such indignity; even less should any ballerina, let alone lovely Claire Calvert, be dragged along the floor on her belly or manhandled like a sack of flour by six male dancers. It was clearly just rotten luck, but by the time Marianela Nuñez suffered an undignified costume malfunction during her pas de deux with Federico Bonelli, it felt like adding insult to injury. The dancers make a game stab at it, like the top-class professionals they are, but only explosive Marcelino Sambé and pantherine Calvin Richardson manage to strike sparks from this wet material; the princely Bonelli and even more princely Vadim Muntagirov do no more than politely going through the motions, and who can blame them? Let’s see no more of this, please.”

Dawson responded with a now-deleted tweet, saying London critics would be delighted to know that he’s decided not to show his work in London anymore if he can help it. The tweet sparked a Twitter campaign of support from his fans.

More surprising though, Dawson’s stager, Tim Couchman waded into the comments section of the review.

“As the stager of The Human Seasons, I would like to say that the ballet you saw was not, in truth, The Human Seasons—it was, as you say ‘a game stab at it’. And if you’d been privy to the staging process, your assumption that all the dancers are ‘top-class professionals’ might perhaps have been challenged. To me, personally, a top-class professional is someone who endeavours to present the art as authentically as possible. They are open to understanding the techniques required to achieve an artist’s particular style and vision, whether they like them or not. They are, in this case, open to falling, twisting, arching, tilting, throwing, sliding, etc. in contrast to being still, square, tense, upright, blocked and closed. A top-class professional makes the effort to learn the physicality, and musicality, properly and precisely. They observe, listen and practice, and they practice repeatedly until they master that which is strange and difficult. They retain the information, come to rehearsals prepared, they focus hard, and deliver the work consistently, without deflecting corrections and coaching advice. They do not bicker and moan about things they think are impossible before they’ve even tried them. A top-class professional puts the needs of the scene before the needs of the self, so that the scene’s integrity is not corrupted—tight, sleek unison doesn’t become loose, rough discord, a smooth canon doesn’t end up a jagged jumble, and narrative build doesn’t turn into ad-lib blah-blah. And a top-class professional (not to mention true artist) would never ever be satisfied with scraping though at the last minute, shrunken with shame, knowing they didn’t really do their best. Only when ALL cast members behave as top-class professionals, can a work of art hope to reveal it’s fragile truth. But when time is tight, when egos are inflated, when hearts are closed and minds are unfocused, all that can happen is the promulgation of lies. And the art is lost, and we will never know.”

Of course, Couchman’s not the first to defend himself against bad reviews: Jenifer Ringer went on NBC’s “Today” show after Alastair Macaulay criticized her weight; Bill T. Jones retaliated against Arlene Croce’s non-review of his Still/Here by saying she had a “frightened and limited definition of normal.”

But sharing details of his frustrations about the process seems to take that one step further—and maybe one step too far? While his comment gives readers insight that maybe the circumstances were less than ideal, shifting the blame to the dancers and calling them unprofessional seems like a low blow.

I guess we can assume he’s not eager to work with The Royal Ballet again.