Teacher's Wisdom: Jennifer Scanlon

Jennifer Scanlon’s calm presence is infectious. As the former Limón dancer approaches, her students exhale, lengthen their spines, and allow

their sternums to soften. But don’t let her guru-like nature fool you; she can also demonstrate the suspensions, overcurves, and side bends of Limón technique with vigor.

Scanlon teaches modern dance and Alexander Technique at Boston Conservatory, imparting a deep-rooted knowledge of José Limón’s heritage and a mindful approach to all movement. In 1963, after attending Juilliard, she joined the Limón Dance Company for a tour of the Far East. During her 21-year tenure with the troupe, Limón made the solo

“Niobe (Mourning Mother)” from Dances for Isadora on her. She was also part of the creation of A Choreographic Offering (1964) and Psalm (1967). Scanlon has traveled the country to set Limón’s repertory at universities and companies like the Joffrey Ballet and Kansas City Ballet. Former student Jenny Dalzell caught up with her to discuss her role as a teacher preserving Limón’s legacy.

What was it like working with Limón?

Challenging, inspiring, and demanding. He was prolific in terms of bringing in material when choreographing a piece. He also had a great sense of humor. When he’d get stuck or stymied, he would tell us these not-so-funny jokes, and we’d laugh and say, “Oh, José, you tell the worst jokes.” We were so much younger, but he was accessible if you didn’t feel threatened by him. He had many interests and was articulate in so many ways. He played the piano, listened to music, and read voraciously. He was a Renaissance man. He was politically astute, and his dances spoke of humanity.

What is the core of Limón technique?

The Limón technique uses the Humphrey-Weidman principles of fall, recovery, and suspension, and of course, the use of the breath is primary. The technique is very grounded, but energy is always moving past your fingertips, and there is a sense of conscious abandonment. You allow the energy of a fall to determine the next moment of suspension. It’s not simply plié-relevé—you cannot force suspension. I tell my students to think of a suspension as a musical fermata or an ellipsis at the end of a sentence, never a period. It has no end; it reaches a place where it becomes a new beginning.

Do Limón classes differ depending on the instructor, or are the exercises codified?

The movement principles in each class would be the same, but José never wanted any kind of syllabus. Limón teachers may share some exercises because we had the same teachers. What I teach is certainly imbued with Limón, as that was my life, but I am an assimilation of all my experiences. My practice of Alexander also plays a big role in my classes.

What aspects of Alexander do you bring into your modern classes?

I often talk about the use of “primary control,” which is one’s head being movable at the end of the spine, allowing a freedom of movement in the rest of the body. One day I led an Alexander meditation of the breath to help students gain awareness of their rib cages and avoid the arms-up/ribs-out syndrome. I had them lie down and put their consciousness inside their rib cage. For five minutes, I asked them to feel and watch the movement of their ribs with their natural breath. When they stood up, I had them stay with the meditation as they raised their arms—and what a difference! It was wonderful.

Many of your first-year students have studied only ballet. Do you have advice for someone entering their first modern class?

Don’t try to translate this vocabulary into something you know. Think in terms of activities, not shapes: You are bending. You are folding. You are standing. In your inner dialogue, use verbs. Go into class with a clean slate; don’t worry about looking awkward. It’s not easy, but you have to be free to fall over and play with ideas.

When casting a Limón piece, what qualities do you look for in a dancer?

My attention jumps to students who are dancing, not those who are trying to dance. I look for dancers who are able to make choices. When I present new material, I want to see you go for it. Especially if I give you feedback, I want to see a change, to see that you can take direction. It’s the flexibility of mind that allows the flexibility of body.

What do you hope your students leave with after every class?

I strive to create a workplace where students feel safe enough to take risks and explore their individual possibilities. I don’t want to present ideas that they only replicate back at me. If I ask someone, “How was that, how did that feel?” I don’t want them to look blank or, worse, ask me, “Was that OK?” I want students to experience themselves in the movement and be their own teachers. I’m there to provide feedback and lead them to new open doors, but they have to walk through and face challenges. I want each one to have a voice, to give themselves permission to explore, rebel, to have opinions.

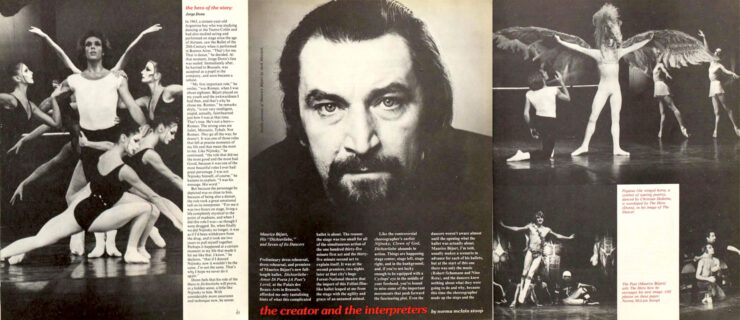

Pictured: Scanlon teaches Limon technique at Boston Conservatory. Photo by Jaye Phillips