What Makes Balanchine's Jewels So Timeless

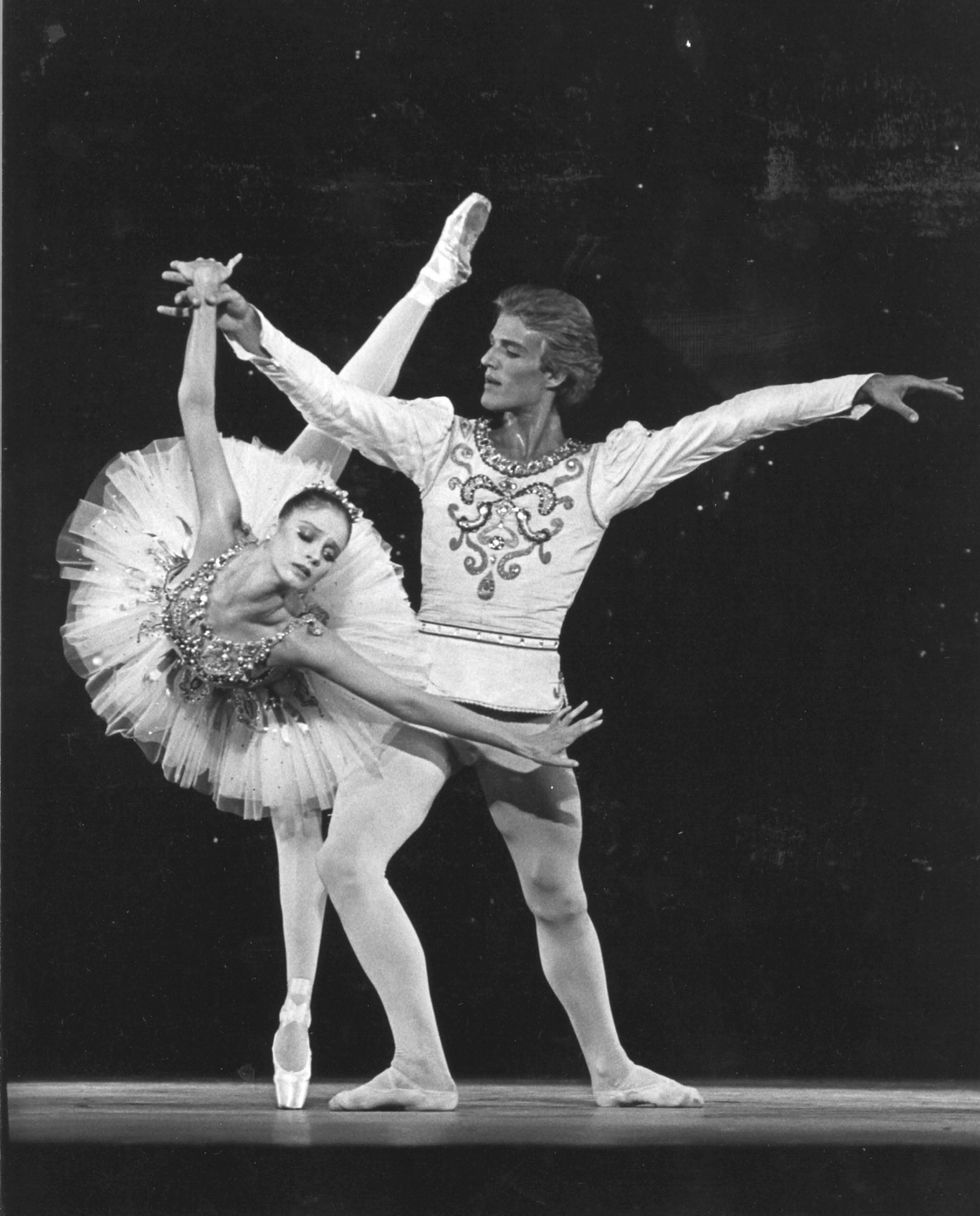

A long time ago, I was a teenager, just hired as a member of the corps with New York City Ballet. I found myself standing in B-plus at the very back corner of the State Theater stage, clutching the hand of fellow teenage corps member Shawn Stevens. Though the expansive stage was filled with dozens of talented dancers, I was most awed by the two who stood front and center: Suzanne Farrell and Peter Martins. With a sudden and sweeping downbeat from maestro Robert Irving, the full power of Balanchine and Tchaikovsky flooded the stage and the final triumphant moments of “Diamonds” began.

Peter Martins and Suzanne Farrell in Jewels. Photo courtesy Dance Magazine archives.

Looking back on that moment, career-defining as I thought it was, I suspect no one except my mother was watching me. Didn’t matter. Being a part of the masterpiece known as George Balanchine’s Jewels was pleasure enough.

Jewels

remains a signature work of the New York City Ballet, but it is no longer an exclusive of Balanchine’s troupe. Jewels is seen and performed by people all over the globe, and on the occasion of the ballet’s 50th anniversary, several companies will perform it this year. The Bolshoi Ballet, Paris Opéra Ballet and NYCB are even sharing the stage this month for a special Jewels performance at the Lincoln Center Festival.

Violette Verdy and Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux in “Emeralds.” Photo courtesy Dance Magazine archives

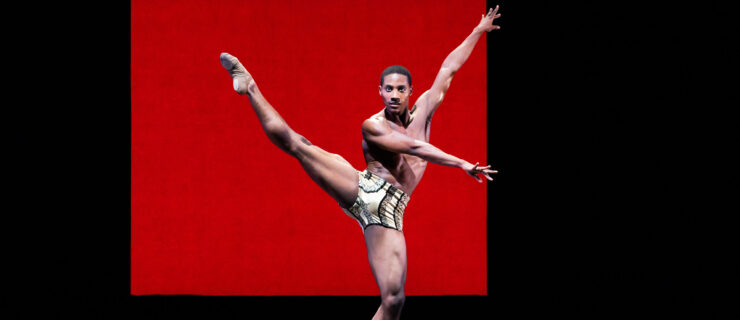

The appeal of Patricia McBride and Edward Villella in “Rubies” was distinctly American, buoyed by the jazz-inflected score by Igor Stravinsky. Each dancer possessed a winsome, girl-next-door/guy-next-door quality—fresh, spontaneous, stepping straight out of the sock hop. Villella recalls Balanchine constantly returning to the playful theme of the filly and the jockey. Villella and Patricia McBride literally trot and prance their way through sections of the piece, at times appearing to hold a riding crop.

“Diamonds” is steeped in the traditions of imperial Russian grandeur—perhaps a tribute to the Mariinsky Theatre of Balanchine’s childhood. Farrell’s headpiece looks like it might have been a gift from the Czarina herself. The harmonious balance and swells of Tchaikovsky’s full-orchestra score, Madame Karinska’s magnificently jewel-encrusted costumes and 34 elegant dancers remind us that the mold-breaker who brought us Agon revered symmetry and pageantry as much as he loved arresting innovation.

He also placed Farrell at the center of this modern-day nod to tradition. Farrell was by no means a traditional ballerina. She was unleashed and unpredictable in every movement, wild and spontaneous with clever phrasing and a willingness to let her long legs fly. With Farrell at the epicenter of this conventional ballet, Balanchine gave tradition a fresh coat of paint, a recast and a makeover. Jewels springs from tradition, building on it, bursting from it and putting another exquisite link in the evolutionary chain of classical ballet.

Young dancers tell me they like the “traditional stuff like Balanchine.” Gulp. (There’s a sudden reaffirmation I’m really not a Millennial.) But the opinions of those savvy teenagers remind us that the breakthroughs of 20th-century artists like Balanchine are not only tradition for a new generation, but timeless art for all generations. Whether they see nationalist themes, extreme physicality or the juxtaposition of tradition and innovation, the relevancy of this great work resounds. Its appeal is as evident in 2017 as it was in 1967.

For this milestone anniversary, Pacific Northwest Ballet is unveiling new scenic and costume designs by Paris-based designer Jérôme Kaplan. When I watch the curtain rise this fall in Seattle, I won’t be standing upstage left in B-plus; I’ll be seated in the audience. But as maestro Emil de Cou ushers in the final sweeping notes of Tchaikovsky’s score for “Diamonds,” I know I will recall the nervous excitement I felt many decades ago, and I’ll share the thrill with thousands who are seeing this masterpiece for the first time.