What's Not Okay to Ask A Dancer to Do?

To create great work, choreographers need the freedom to tackle difficult subjects and push physical limits. But when your instruments are human beings, is there a limit to how far you should go? Five choreographers open up about where they draw the line.

Elizabeth Streb

ioulex, Courtesy Streb

“I ask dancers to be 100 percent trained in every fiber of their bodies so they can come in here ready to crash and fly. I think any dancer who says, ‘No, I don’t want to do that’ isn’t curious enough to be in the STREB company. They can say, ‘I’m not ready to try that today.’ And they can say, ‘Let’s not do that again.’ When a dancer gets injured, I wish on that day I had stopped it. But we agree to get hurt.”

Raja Feather Kelly

Hope Davis, Courtesy Kelly

“If my dancers can debate me into understanding their position and win the argument, then I’m happy to concede. There was a situation where a cast member told me something wasn’t important to the show, and I thought it was. We had an argument. I think I wanted her to make out with another dancer. I don’t want to allude to kissing if I think the scene should end with a kiss. But she didn’t think that it was justified for the purpose of the scene, and she felt that it exploited her. In the end, I believed her. It wasn’t moving the story forward, so we didn’t do it.”

Pat Graney

Courtesy Graney

“When I was younger, I didn’t fully understand how far my dancers would have to go emotionally to do the intense, outrageous stuff I wanted. Sometimes you’re just directing and you’re in your own dreamlike place. I’d say, “Oh, come on, you can do this,” or “Haha, that thing you did was really funny,” and it really wasn’t. Now, I have more compassion.

“A lot of my material is based in their individual experiences, so I just let my dancers go as far out as they’re gonna go. But I do put the kibosh on some things. For example, one dancer wanted to tape herself into a plastic bag. I thought, That’s a little dangerous. She tried it, but it made me feel so panicked I couldn’t really watch it. I couldn’t put that onstage.”

Danielle Agami

Cheryl Mann Productions, Courtesy Agami

“You just need an honest conversation. When it’s risky—I recently wanted to deal with the physicality of meth addicts, for instance—I make sure I start the discussion by asking, by wondering, not demanding anything from anyone. We have a dialogue and I give the person the freedom to say what he thinks because I need to have a collaborator with me. If I feel a dancer is uncomfortable, I retreat. It doesn’t prevent us from dealing with struggle and effort and challenge and embarrassment and fears, but I don’t want to humiliate anyone, including the audience.”

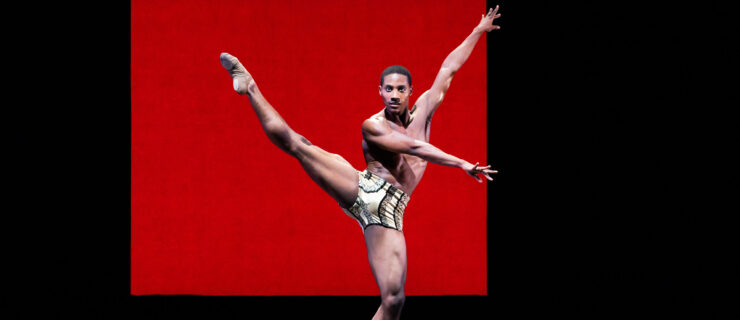

Alonzo King

Bill Zemanek, Courtesy LINES

“If someone feels uncomfortable, they’re not going to be able to serve the work, so it’s pointless. When LINES worked with the Shaolin monks, I wanted some pas de deux and initially they said it was their rule that they did not touch women. So I left them alone. But when they realized that the movement was not sexualized, these were just ideas that we’re working out through physical form, then everything began to change, and they saw it as okay.

“Now, if you’re talking about technical demands, you have to push dancers! [Laughs.] Because as a director, you also want to feed them technically and artistically. You will not allow them to say “I can’t,” because those demands represent the next step in their development.”