Amar Ramasar is at The Top of His Game

New York City Ballet’s Amar Ramasar has grown into more than just an endearing kid from the Bronx. In recent seasons, he’s become an intriguing, sophisticated artist. But he still can’t help radiating his love for dance.

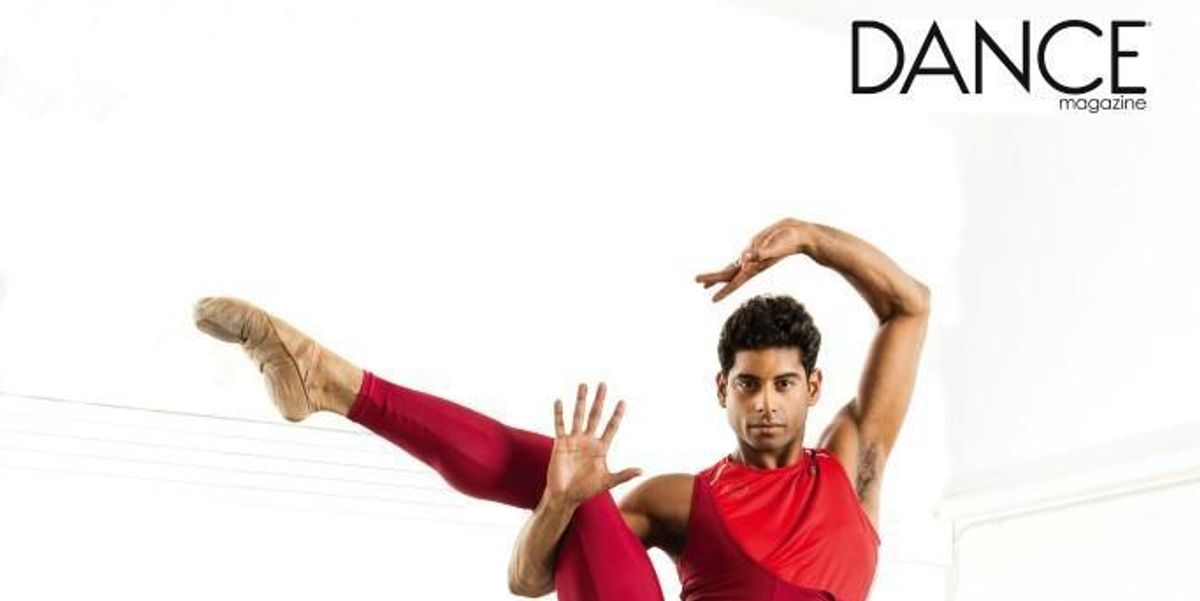

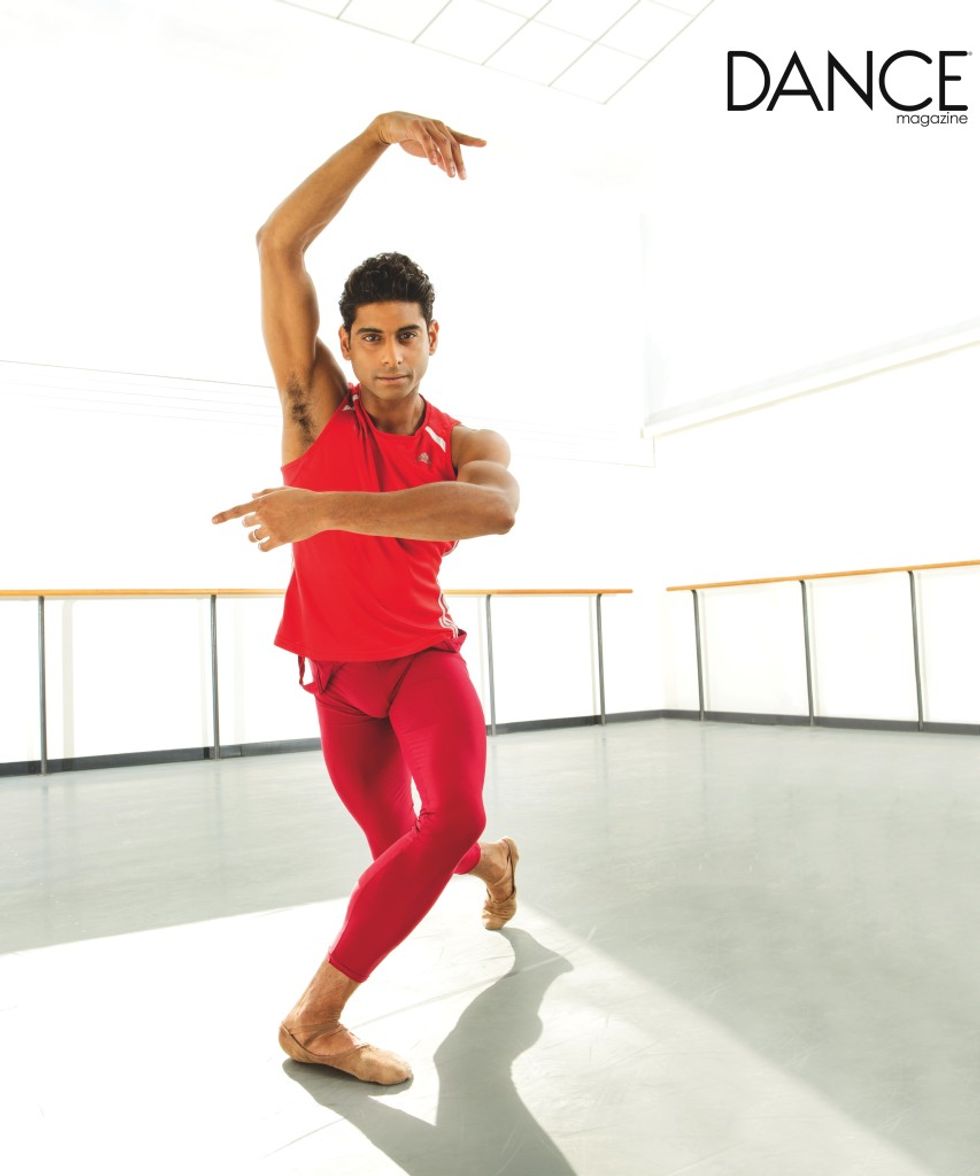

Ramasar’s favorite red shirt is a hand-me-down from Christopher Wheeldon. Photo by Jayme Thornton.

In a large studio on the fifth floor of the David H. Koch Theater, Amar Ramasar and four women from New York City Ballet’s corps are rehearsing “Phlegmatic,” from Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments. Ramasar goes through his solo, analyzing each step as if attempting it for the first time. Energy shoots through his fingers in an arabesque penchée. His face beams as he pops through a thicket of women’s bodies, like a jack-in-the-box. When he and his four backup dancers do a sequence of développés to the side, his legs reach up as high as theirs, the line completed by a sharply pointed foot. “It hurts, Rosemary, it hurts!” he jokes to the ballet mistress, Rosemary Dunleavy, in mock agony after one of these impressive extensions, then begins again.

Photo by Jayme Thornton.

Afterwards, he thanks the pianist, hugs Dunleavy and high-fives his fellow dancers. Everyone agrees: Ramasar is a mensch, as quick to give encouragement or welcome a newcomer as he is to pick up choreography or find a solution to a partnering riddle. At 34 and clearly at the top of his game, he is unfailingly modest. This sunny disposition, and the adaptability that underpins it, has served him well in a profession that is at times grueling, and never easy.

His own path has certainly demanded a certain amount of grit. He started ballet relatively late—at 12—after taking part in a New York City–wide after-school musical theater program called TADA! Daniel Catanach, a teacher and choreographer then working with TADA!, noticed him right away. “He used to follow me around,” says Catanach, “asking, ‘When do I get a solo, when do I get a solo?’

Because he could see how much Ramasar loved to dance, Catanach showed him a video of Balanchine’s Agon. Something awoke in Ramasar: “I fell in love. I thought, ‘I can do this.’ The four guys standing there—I could relate to it. It had almost a street vernacular, like hip hop. I had done lots of hip hop with my friends after school.” Catanach, a mentor whom Ramasar refers to as his uncle, arranged for an audition at the School of American Ballet. He got in.

It turned out that ballet was a lot harder than it looked. The boys standing next to Ramasar at the barre were four or five years younger and already knew what they were doing. “I was the tallest in my class, and a little chubby,” he says, “and they were all so beautiful, with the right facility and physique.” He felt inadequate and unsure of his gifts.

His awareness of being different, a mixed-race dancer in an art where whiteness is still the norm, may have played a part. But it’s not something he talks about readily. “I’ve encouraged other boys of color to audition for SAB,” says Catanach, “and they couldn’t deal with the lack of diversity. But it didn’t affect him. He was there to dance.” Ramasar never complained. “I figured if I cried my mother would pull me out,” he says, “so I put on a good face.” At least classes in the boys’ program at SAB were free—otherwise, ballet training would have been beyond the family’s means.

Ramasar in The Four Temperaments. Photo by Paul Kolnik, courtesy NYCB.

Though Ramasar’s parents were okay with his studying dance, neither could take time off of work to usher him to and from class, so he got used to navigating the subways from the Bronx at a young age. (“I had the longest commute of anyone,” he says.) His mother, Merida, is originally from Puerto Rico and worked as a nurse. His father, Churan, is of Indian descent, from the island of Trinidad; he is a computer technician. It was a multicultural home, in which both the Hindu and Catholic religions were observed. There was a lot of music: “My mother taught me every Latin dance that was ever invented,” Ramasar says, smiling. “Salsa, merengue, bachata, all of it.”

Ramasar’s parents wanted him to be a doctor or a scientist, particularly after he was accepted at The Bronx High School of Science, a prestigious public school in New York City. It wasn’t until he danced the lead in Balanchine’s Danses Concertantes at SAB’s year-end workshop, he says, that they fully realized what their son had become: a professional dancer.

A few months later, in 2000, he was taken into the company as an apprentice. From the beginning, Peter Martins, NYCB’s ballet master in chief, pushed him: “He said, ‘You need to work on your fifth position. Remember, that’s the base,’ ” Ramasar recalls. He had a natural affinity for the more contemporary ballets, but the elongated, clean, relaxed lines associated with classical roles have taken him longer to acquire. The process of reining in his almost manic energy also took time. “In the contemporary pieces it didn’t matter so much if you had flat turnout and perfectly straight knees, but that was what I was trying to obtain,” he says. Still, there was something about him that made you want to watch him move.

He became a soloist in 2006, and a principal three years later, but his rise has not been as steady as the timeline might imply. “I had a lot of growing up to do. I had to work harder,” he admits. “It was a hard plateau to pass.” But in the last few years, he has found a new focus. He religiously attends morning class, though he confesses to hating barre. “It’s just the rawest kind of bare vision of your technique,” he explains. “You can’t hide the problem at barre.” The work has paid off, particularly in recent seasons; his footwork has become clean, his jumps sharp and explosive, his musicality fine-tuned. He has acquired style and presence. These days he’s less apt to mug for the audience, an endearing tendency from his younger days. He is moving into more rarefied territory: Monumentum pro Gesualdo, “Emeralds” and the diaphanous pas de deux in the second act of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. One day, he hopes to dance “Diamonds.”

Ulysses Dove’s Red Angels. Photo by Paul Kolnik, courtesy NYCB.

Meanwhile, he has worked with practically every visiting choreographer, from Alexei Ratmansky to Liam Scarlett, Angelin Preljocaj to Kim Brandstrup. The young resident choreographer Justin Peck has used him in several works. He’s danced plenty of Robbins (including Robbins’ own role in Fancy Free), as well as much of the modernist Balanchine repertoire, including the ballet that got him hooked in the first place, Agon. Some nights at the Koch, he barely leaves the stage. “No one can do everything,” says Peter Martins, “but Amar comes close.”

In fall 2014, Ratmansky created a role for him in his new Pictures at an Exhibition. His character appeared to be a kind of sorcerer, conjuring up a storm with his arms and legs. Ramasar jumped and twisted, slapped his thighs and launched into a demented-looking Charleston. He ensnared a woman (Sara Mearns) in his arms, lifting and twisting her in the air, then spiraled off on his own. Every movement looked slightly unhinged and at the same time sharply etched. It’s difficult to imagine anyone else stepping into the role. Maybe that’s what happens when a dancer comes into his own—every role becomes an extension of his personality. One thing is abundantly clear: Ramasar is exactly where he wants to be.

Marina Harss writes on dance for

The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Nation and other publications.