"Ballet Is Woman"? Not in the Artistic Director's Office

In America, Balanchine’s famous quote does not apply offstage. Last week The Richmond Ballet convened a panel to examine the question, Why aren’t more women in charge of ballet companies? I came away from a discussion of and by a group of female artistic directors on the generally male-dominated leadership of American ballet companies with more questions than answers. The panel, titled “The Glass Slipper Ceiling,” was put together by the Richmond Ballet under artistic direction of Stoner Winslett. Participants were Andrea Snyder (executive director of DanceUSA), Anna Kisselgoff (former chief dance critic of The New York Times); Celia Fushille (artistic director of Smuin Ballet); Victoria Morgan (a.d. of Cincinnati Ballet); Dorothy Gunter Pugh (founder and a.d. of Ballet Memphis); and Ms. Winslett herself. (Suzanne Farrell was to have attended but could not due to a last minute scheduling conflict.)

The climate that gave rise to this panel: All top-tier ballet companies (budgets over $7M) in the U.S. are run by men. Of the next tier down, only four companies are run by women, all of whom participated in the panel. This male domination of leadership roles is not true outside the States; England’s Royal Ballet, France’s Paris Opéra Ballet, the National Ballet of Canada, and the Royal Ballet of Flanders, are all run by women.

Kisselgoff, as moderator of the panel, provided a fantastic historical perspective, and asked great questions herself. She pointed out that many major American ballet companies had been founded or originally directed by women, but that by the 1980s, ballet company leadership had become overwhelmingly male. She attributed this to the star power and draw of artistic leaders such as Balanchine, Nureyev, and Baryshnikov. But she questioned why, as soon as ballet companies became institutionalized (and thus legitimized), women faded from leadership roles. Ms. Snyder pointed out that this was also around the time when nonprofits began to adopt corporate, “business-like” models of operating, which at the time lent themselves to male leadership.

The women, most of whom had not originally set out to direct companies themselves, agreed in general that when they first stepped into leadership roles and met with other directors at conferences and meetings hosted by the likes of Dance/USA, they faced a sort of “boys club” atmosphere. Dorothy Gunter Pugh noted that more recently, with a younger generation assuming directorial roles, that atmosphere has softened—less pontificating, more asking questions.

The panelists offered a wonderful range of experience and perspectives: Pugh, in particular, noting that while balancing her company with family demands has been “a juggling act, I’ve created what works for me.” Winslett recounted her founding of a dance school in a neighbor’s basement at age 13.

Yet I found myself wanting more pointed answers to Kisselgoff’s questions—answers that moved beyond the women’s individual experience and addressed issues of the field as a whole (although Snyder, whose position provides her with excellent and far-reaching insights into exactly that, did offer excellent information). I want to know: Are female dancers encouraged with equal enthusiasm to choreograph? Do they have access to similar mentorship opportunities as male dancers, opportunities that might foster their potential as leaders and directors? Are they encouraged to even think of directorship as a possibility? And if not, can the field’s current leaders begin to fill these gaps? How?

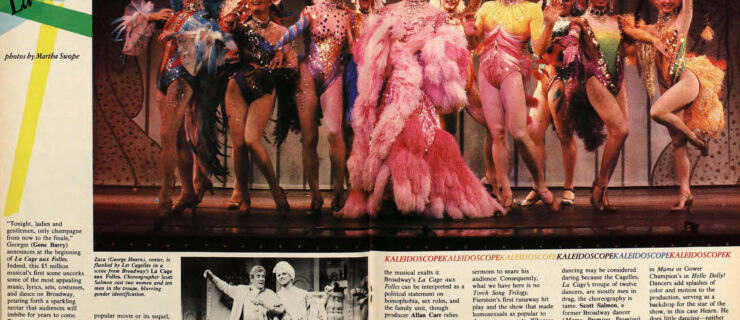

Left to Right: Celia Fushille, Victoria Morgan, Andrea Snyder, Anna Kisselgoff, Stoner Winslett, Dorothy Gunther Pugh

Photo by Aaron Sutton, Courtesy Richmond Ballet