What It Takes to Radically Reimagine "West Side Story"

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker

is celebrated across the dance world for her stripped-down, stubbornly abstract choreography; Ivo van Hove across the theater world for his stark, stubbornly tech-heavy reconstructions of plays and movie scripts. But after this week, the two Belgians are likely to be famed, for good or ill, as the pair who kicked Jerome Robbins out of West Side Story, the classic musical he conceived, directed and choreographed to everlasting acclaim in 1957.

Their souped-up, polarizing new production, opening February 20 at the Broadway Theatre, retains the original Robbins idea, transplanting Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into a contemporary New York beset by bigotry and gang warfare. They’ve kept most, if not all of Arthur Laurents’ book, Leonard Bernstein’s music and Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics.

But van Hove decided that to bring their Tony and Maria into 21st-century New York, he had to jettison Robbins’ iconic, Tony-winning choreography—preserved in the Oscar-winning 1961 movie and in dozens of restagings around the globe.

De Keersmaeker understood the enormity of the undertaking, and hesitated for what she recalls as “a long time.” She’d never worked on Broadway, she’d never dealt with what she calls “such a big structure,” and, she says, “People say Jerome Robbins is God—what do you do with that?”

But she knew from the start she wouldn’t say no. “If somebody asks you to do a musical, you might as well do this one,” she says. “It’s not a revival of an American classic—it’s a revival of the American classic, the most iconic piece in the American theater.”

Shereen Pimentel and Isaac Powell in West Side Story

Jan Versweyveld, Courtesy DKC/O&M

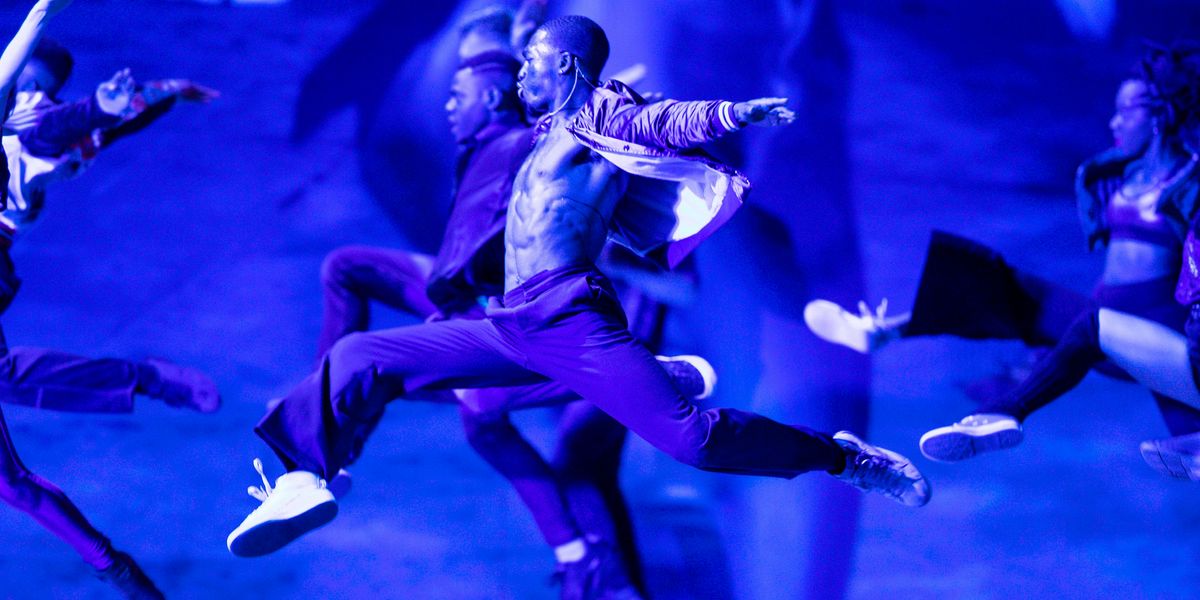

As is clear in the limpid, geometry-inspired work she makes for Rosas, the Brussels-based company she founded in 1983, and in the thrusting, throbbing choreography she’s made for the Jets and the Sharks, she doesn’t scare easily.

Like most Europeans, she’d first seen West Side Story in the film version, as a young teenager. She enjoyed it, she recalls, though “I didn’t have the kind of once-in-a-lifetime encounter that I think a lot of people had. I liked the way the music, dance and theater came together. I liked the dancing a lot. But it was not life-changing. Bambi,” she adds, “made a bigger impression.”

Later, when she went to study in New York, Robbins was not among her touchstones.

“My relationship to American dance has mainly been to postmodern dance, the post-Cunningham generation,” she says. “Lucinda Childs and Bob Wilson, Trisha Brown, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton—these people are my reference points. I never followed the work of Balanchine and Robbins that much. When I was at NYU, in the ’80s, I had the chance to see a lot of the American avant-garde, and I saw quite a lot of Broadway, too. But I would mainly connect to the downtown scene.”

The downtown scene is where, a decade later, the Amsterdam-based van Hove would direct quirky stage versions of classic texts, eventually wowing Broadway in 2015 with his Tony-winning production of Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge. De Keersmaeker had long wanted to work with him, she says, “but we never found the right project.”

As she discusses their collaboration on West Side Story, the word that comes up most often is “intense”—”I sort of had to leave my comfort zone and Ivo had to leave his comfort zone,” she says.

The challenges extended beyond the obvious. “Ivo made it very clear from the beginning,” she says, “that we want to tell a story. So the words that are spoken, the images that are projected, the costumes, the sets, the lights, and, of course, the dance—they have to serve the story. That was the moment, really, where I had to learn how to sharpen my pencils.”

She also had to cope as identity politics, sexual politics and cast injuries intruded into an already tricky process.

Shereen Pimental, Isaac Powell and the cast of West Side Story

Jan Versweyveld, Courtesy DKC/O&M

De Keersmaeker knew from the start that it wouldn’t be easy. Just casting the show took over a year and a half. “People had to be able to dance well—not only, let’s call it ‘traditional’ Broadway dance, but also my vocabulary, the Rosas vocabulary. They had to be able to sing—the music of Leonard Bernstein is very sophisticated, difficult music. And the Sharks had to be exclusively Latino. We wanted young people—two thirds of the cast are making their Broadway debuts. You want people who are technically skilled but who also are fresh, who are very individual but also harmonious and differentiated as a group, and who are strong enough to go into this Broadway challenge of playing eight shows a week.” She and van Hove auditioned more than 1,500 people in New York, Miami and Los Angeles.

The 40-plus performers who became the 21st-century Jets and Sharks were diverse in ethnicity—both gangs are multiracial—and in their dance styles, from New York City Ballet star Amar Ramasar, who plays Bernardo, to veterans of Philadanco, Trisha Brown, Pilobolus and “So You Think You Can Dance.” Melding them into a unit, De Keersmaeker says, meant trying “to harmonize all the different inputs without wiping them away.” It wasn’t just technique, “but also their very way of physical being, their emotional being…. It was a challenge to stretch my vocabulary and my language without losing the integrity of it.”

When the dancers playing Sharks asked for choreography with more Latin authenticity, the production added former Miami City Ballet principal Patricia Delgado and Tony-winning choreographer Sergio Trujillo as consultants. De Keersmaeker points out that Jerome Robbins had done much the same thing in asking Peter Gennaro to work with the Sharks in the original West Side Story, and that she’d brought in outside experts for other work. “There’s certain material I just don’t know,” she says. And, she adds, “There were a lot of different people who assisted—there was a fight choreographer, there was an intimacy choreographer, I prepared a lot of material with Rosas dancers, and for ‘The Dance at the Gym,’ there was a dancer who specialized in house dancing.” She also looked into hip hop, break dance, martial arts, and she was happy to have help. “I wanted to know how young people dance when they go clubbing.”

Still, she tried to work “the same way I always work with Rosas dancers—I propose vocabulary, I give the initial framework, and then the dancers propose material also. But I take the final decisions. I want to keep it very close to my own body.”

With others in the mix, she admits it was “a delicate operation. When you change the choreographer, you change very nature of the movement.”

But by that point, she’d already had to alter her work to suit van Hove, whose approach included a rainstorm and extensive video footage. “It’s a different situation, a different creative situation, than when I work with my own dancers,” she notes. “The key is not that you want to compromise, but that you want to make it as good as possible—you shouldn’t lock yourself up in a kind of ego thing, of ‘this movement belongs to me.’ ”

De Keersmaeker points out another difference between Rosas and the West Side Story company: Musicals are entertainment—”built to deliver what they call Broadway numbers.”

Those numbers took a big hit when the company moved from the rehearsal hall to the theater—the first time the team could see the interaction between the movement on the stage and the movement on the gigantic video screen that serves as backdrop. “It was,” she says, “an exercise and a challenge to find the right balance.”

She’s equally judicious in talking about the controversy that erupted over the casting of Ramasar, whose expulsion and then reinstatement at NYCB over sexually explicit photographs led to demonstrations outside the theater. “My working experience with Amar has been only positive,” she says. She adds that “a century after the Suffragettes, there is still a long way to go to get equal rights for men and women.”

Amar Ramasar, Yesenia Ayala and the cast of West Side Story

Jan Versweyveld, Courtesy DKC/O&M

With just a handful of previews left for tinkering, she’s asked how her West Side Story compares to the original. “That’s a difficult one,” she replies. She says she’s tried to honor the way the Robbins dances evolve out of casual, everyday moves. “There’s something about simplicity and readability in Jerome Robbins’ movement that is extremely efficient.”

At the same time, she says, “I think bodies are the same and different than they were 60 years ago. Because the world is more complex. The complexity of the world is in the bodies of today.”

She suggests that her choreography is more about “accepting gravity” than the original, and that perhaps Robbins relied too much on “the clarity of classical ballet architecture.” Ultimately, she says, being an outsider worked to her advantage, because van Hove’s imperative was “very clearly…to make something new, to go for something different…. It definitely protected me from being overly anxious.”

She’s not ready to answer one more hard question: Will she do another Broadway musical? “We haven’t had the premiere yet,” she says. “Let’s think about that after we finish this one.”