Are We Too Precious With Classic Dance Works?

Choreographer Natascha Greenwalt loves the music of Swan Lake, but she has a few problems with the ballet itself.

“I don’t see this love story,” Greenwalt says. “I see—there isn’t consent.” To her, Siegfried seems predatory, Odette seems far too apologetic, and the Odette/Odile duality reinforces toxic tropes about women who are either dangerously sexy or not sexy enough.

“Not to mention he’s been presented with every human woman in the land, and he goes for a bird,” she says with a laugh. “Like, you’re never enough.”

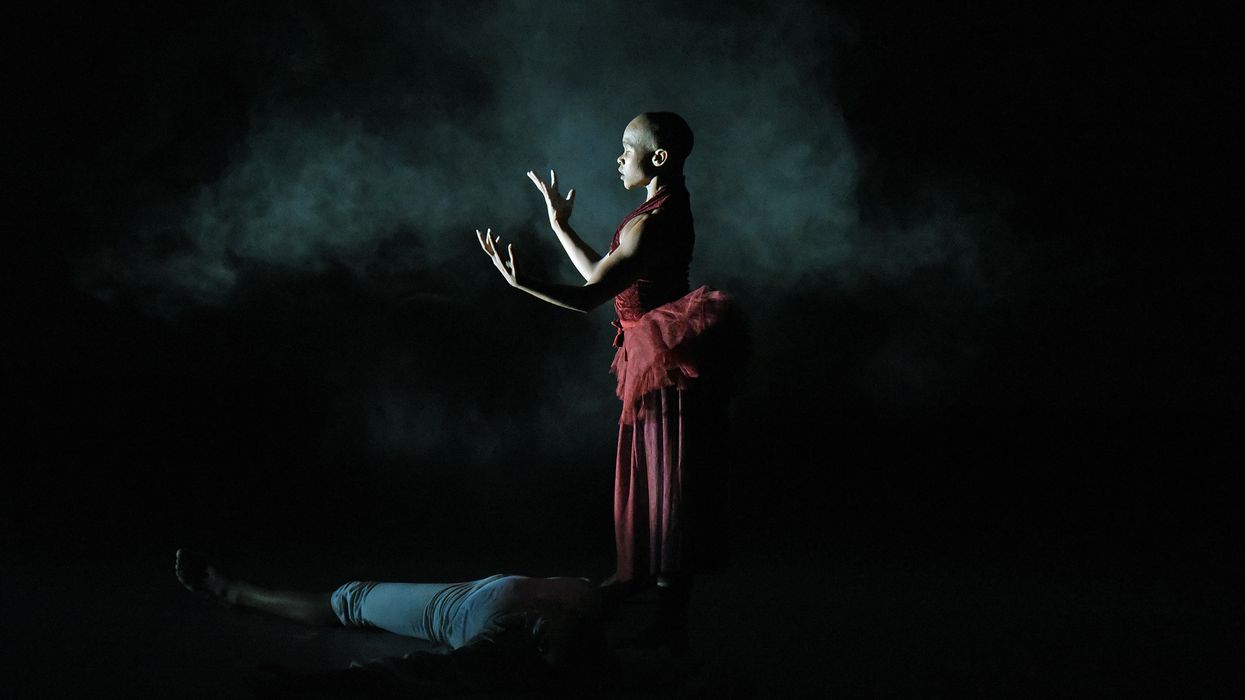

Greenwalt decided to make her own version of Swan Lake for the company she co-directs, Coriolis Dance. Working on her piece, Danses des Cygnes, she initially felt daunted taking on one of the most famous works in the ballet canon. But in the age of #MeToo, with women asking for their stories to be heard and sexual assault a major topic of discussion, she also saw an opportunity to bring the age-old work into a very contemporary conversation.

In her version, Odette is a human woman who chooses to become a swan, drawn to the sense of community among the birds, and Siegfried is a swan who violates her. “I felt like, Here’s my chance to take a story I find deeply problematic, and a vocabulary that’s really familiar to audiences, to be able to retell my own story,” she says. “My ballet is a commentary on what I experience in seeing Swan Lake, more than trying to replicate what I think it is.”

Coriolis Dance’s Danses des Cynges

Bret Doss, Courtesy Greenwalt

Like Greenwalt, many artists have found their own ways of reimagining canonical dance works, by creating productions that speak to the concerns of today’s audiences, experimenting with setting or genre, or interrogating problematic elements.

But compared to other art forms, the dance world can also feel particularly resistant to change, whether from choreographic trusts, diehard classicists or others who fear the loss of a choreographer’s legacy. Updating a 19th-century story ballet or a hallmark work of modern dance can feel taboo.

South African choreographer Dada Masilo, who has reworked several story ballets, says that when she tackled her first couple projects, “I felt like I was stealing a cookie from the cookie jar.”

It’s true that dance history is particularly hard to preserve, and the desire to stay true to a choreographer’s original intention when restaging their work is a valid one. But treating these works like museum pieces can backfire.

In the effort to stay painstakingly authentic to an original artist’s work, are we missing some of the spark that made it so exciting when it premiered, and losing the element that made it a classic in the first place? Are we preventing these works from resonating with new audiences?

Colin Connor, the artistic director of the Limón Dance Company, believes presenting José Limón’s works in a slightly different context can help today’s audiences better connect with their original message. To Connor, much of Limón’s work was influenced by his position as a Mexican immigrant in the U.S., and his experience of the society he lived in—though he didn’t always make the reference explicit.

“He often made works about the time he was living in, but he would layer them or hang them on traditional, accepted classic tales,” says Connor. The Traitor, for instance, was a response to the McCarthy era, but Limón told it through the lens of the Biblical story of Judas betraying Jesus. “I’m not sure, if he were here today, whether he would go, ‘I don’t need to couch this in old stories, I can say exactly what I feel right now,’ ” Connor says.

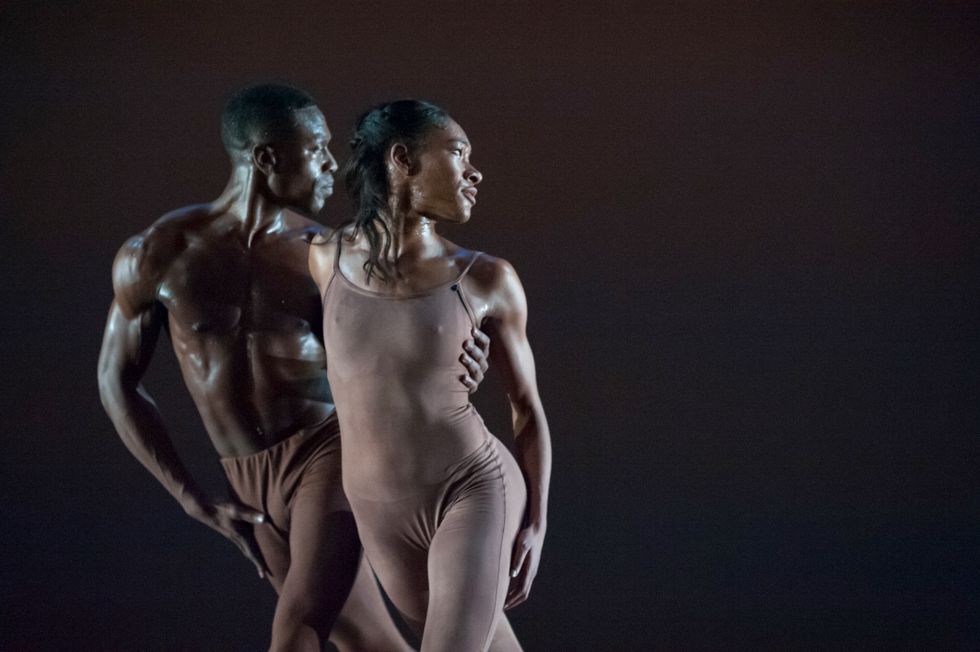

The company took this idea to heart when they performed Limón’s The Exiles, a work based on the expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, at The Joyce in 2017. It was the year President Trump instituted a travel ban for majority-Muslim countries, at a time when the rights of immigrant groups have come increasingly under attack in the U.S. The piece’s choreography was left untouched, but the dancers wore simple clothes instead of the traditional unitards and green vines. In place of the Schoenberg score, the company commissioned an a cappella one by Serbian composer Aleksandra Vrebalov.

“This idea of refugees and immigrants, and a couple who arrive here with nothing but themselves—that’s a completely contemporary story,” says Connor. Presenting the piece in a more modern way gave people a fresh way of understanding its themes. “These kinds of things happen in the theater world all the time,” says Connor. Shakespeare classics, for instance, are often presented in current day contexts. “In the dance world, by trying to hone to a perceived authenticity,” Connor adds, “I think we can get away from what is really the reason those works were made.”

Limón Dance Company in an updated version of The Exiles

Kiera Chang, Courtesy Limón

Choreographer Matthew Bourne has built his career on creative adaptations of well-worn stories—a Swan Lake where the prince is navigating his sexuality, or a Cinderella set in London during the World War II blitz. “Sometimes it needs a new take to wake the audience up as to what the piece is all about,” he says. “One of the things that happens with classic stories is we get used to seeing them in the same way, and we stop listening and we stop watching. We’re not really thinking about the piece anymore.”

For a decade, choreographer Hope Mohr has run the multidisciplinary Bridge Project, which aims to combine art with social justice. She focused the latest iteration on engaging with Merce Cunningham’s legacy, commissioning 10 artists from various disciplines (including several from outside of dance) to participate in a residency with former Cunningham dancers Rashaun Mitchell and Silas Riener. The group learned about Cunningham’s work while preparing to create their own projects inspired by it. History and creation happened alongside one another.

“Of course there is immense value in honoring a choreographic legacy with historical fidelity,” says Mohr, “but I also think there’s value in unpacking how the work is relevant today to artists working in lots of different contexts.”

To Mohr, it’s important to challenge the very idea of canon itself, and also to consider who has traditionally been left out. Her latest Bridge Project is about bringing Cunningham’s work into the present and acknowledging today’s realities.

“The value for me of looking back is to look forward,” she says. “It’s an interesting question for all of the commissioned artists about how much to let politics and the world as we know it now into their conversation with Cunningham.”

Connor stresses that Limón, and modern choreographers like him, were each responding to their own present, their own moment in time. They were forward-thinking and boundary-pushing. To keep their work static is arguably contrary to the ideals they stood for.

Janet Eilber, artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company, agrees. “She was always experimenting, always trying something new. That’s really the core of her personality,” she says of Graham. “It doesn’t serve her legacy at all to try to cordon it off, keep it in a locked box and never let it grow and breathe. It’s just not who she was.”

While the Graham company still frequently performs the standard versions of works like Appalachian Spring, the company has also engaged with Graham’s work in a variety of ways. In a project called the Clytemnestra ReMash Challenge, they posted videos of solos from Graham’s Clytemnestra online, asking people to create their own short videos connecting the ancient characters to our time. In a residency at Google in 2018, the dancers improvised inside a 3-D paintbrush environment using Graham technique. And in the company’s ongoing Lamentation Variations project, choreographers from across the dance world create new works inspired by Graham’s classic Lamentation.

“These offshoots of creativity inspired by her work are in themselves quite complex and profound, because they’re being born out of her work,” says Eilber. “We kind of realized the depth and breadth of our legacy by releasing it, in a way.”

Some of these projects, Eilber says, are born out of necessity—financial and otherwise. Lamentation Variations originally started as a way to commemorate the anniversary of 9/11. Other works are excerpted so they can travel. To tour Dark Meadow, a 45-minute work with a large set by Isamu Noguchi, internationally, the company created a shorter suite that features the ensemble dancing and partnering that the piece is best known for.

“It allowed us to take that extraordinary choreography to places that never would have seen it unless we did something like that,” Eilber says.

Matthew Ball as The Swan and Liam Mower as The Prince in Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake.

Johan Persson, Courtesy New Adventures

Masilo, too, says that part of her goal in reinterpreting the classics is to make them more accessible to people in her community. “In Johannesburg there were a lot of people that did not understand classical ballet,” she says. By setting her Giselle in rural South Africa, she could contextualize it within South African culture and rituals—for instance, the character of Myrta is a traditional healer called a sangoma—and tell the story in a way her community could connect with.

Bourne also stresses the importance of making sure viewers can follow along even if they have no prior knowledge of ballet or modern dance.

“I feel we have to be very conscious of how we can create the audiences of the future,” he says, adding that this doesn’t necessarily mean changing everything about a work. It’s more about loosening the grip on tradition just enough to help audiences connect. “You see productions of Swan Lake where the swan queen never looks at the prince, and you think, Well, that’s not helping us,” he says.

Taking a fresh approach to a work can also be a way to deal with problematic elements that run the risk of alienating potential audience members. In fall 2017, New York City Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin and arts administrator and educator Phil Chan began talking about how Asians are depicted onstage in classical ballet, starting with the Chinese divertissement in The Nutcracker.

Through discussions with leadership at NYCB, slight adjustments were made to the choreography, makeup and costuming—things like removing the Fu Manchu mustache and geisha wigs and changing caricatured movements like finger-pointing and head-bobbing.

From there, Pazcoguin and Chan started the Final Bow for Yellowface initiative, asking other leaders in the field to pledge to rethink offensive portrayals of Asians onstage, for example, in works like La Bayadère or Le Corsaire. By the end of 2018, leaders of nearly every major American ballet company had signed on.

“There are these works from the Western canon that have a lot of artistic merit, but they’re not the most respectful because they just didn’t have Asian collaborators in the room,” says Chan. “So now that we’re in this position, how can we still keep those works, keep the intention of the choreographer, while making it so that audiences today can still enjoy it?”

Reconsidering how a work reads today can take many forms. “Sometimes you don’t need massive change, sometimes it’s just an approach,” Pazcoguin says. When she played the woman with the red purse in Jerome Robbins’ Fancy Free, Pazcoguin was sensitive to the gray area between a flirty moment and one that looks nonconsensual—and made sure to discuss it with the ballet master and the men playing the sailors. Although they did not change Robbins’ choreography, they shifted the level of sensitivity.

“All of a sudden it looks like a consensual dance where a woman is taking charge of her sexuality and playing and flirting, as opposed to being overwhelmed by three sailors,” she says.

Smart programming choices can make a difference, too. “What if Fancy Free was paired with a feminist ballet that’s talking about what it feels like to be catcalled?” says Greenwalt. “How could programming give context and let it be a conversation, and still let what’s good about the works exist?”

Pazcoguin and Chan stress that their main goal is to prevent companies from losing audiences, and to help the work evolve as audiences do. “People have accused us of being the PC police. Really our intention is to change these works so they don’t die,” Chan says. “If we don’t change, these works will be deemed racist and will go out of the repertory, and we do not want that to happen.”

Ultimately, reimagining classic works is often more about broadening than narrowing. And for many of these pieces, there’s never really been one definitive version anyway.

“Dance is a living, breathing organism,” Pazcoguin says. Choreographers like Balanchine continually revised their own work while they were alive, or made changes for certain dancers. In his solo Chaconne, Connor points out that Limón edited out a whole section of the Bach music he choreographed to, unafraid to do his own tinkering with the classics.

“I think the classics are always going to be there, and we’re always going to cherish and respect and love them, but if people want to try out new ways of reinterpreting them, they should be allowed the space to do that,” says Masilo. “There are always different ways of tackling a narrative.” Those different ways don’t necessarily have to cancel each other out.

“I wouldn’t say the pieces I do are there to replace the classics—I love the classics and I want to still see them done really well,” Bourne says, “but as an alternative take, it makes both viewings very rewarding. They can be complementary, I think.”