How Do You Convince A Patron To Give Their Money To Dance?

Behind every virtuosic performance, there is a quiet group of champions. Private patrons are critical to the success of American dance companies. Most large troupes only generate about half of their operating budget from ticket sales, while smaller companies recoup only a fraction. In a country with minuscule government funds allocated to the arts, individual contributors play an indelible role in financing concert dance.

Why Would You Give Money to Dance?

Richard Kirschner support Elisa Monte Dance because he believes having a wide variety of artists makes our communities richer. Here with director Tiffany Rea-Fisher. Photo by Leslie Hanson, courtesy EMD

Richard Kirschner support Elisa Monte Dance because he believes having a wide variety of artists makes our communities richer. Here with director Tiffany Rea-Fisher. Photo by Leslie Hanson, courtesy EMD

Who are these vital donors, and why have they chosen to support dance? For most patrons, their love of the art form is integral to who they are as a person. Many support organizations to join a vibrant community, and make connections to others with a shared sense of impact. Getting to know the dancers is another key motivator; these direct interactions make the donor experience rewarding.

Some have a personal connection to dance. “I’m a lifelong ballet student, and continue taking adult ballet classes three times a week,” says Laura Chapman, a Boston Ballet patron for nearly 25 years. “I give to dance because the arts are critically important and they always need support. Ballet truly enriches lives.”

Other donors want to help build the kind of community they want to live in. Richard Kirschner, Elisa Monte Dance’s longest-standing board member, says he feels a responsibility to support smaller companies like EMD because he believes a wide variety of artists is an integral part of our nation’s cultural enrichment.

In What Other Ways Are Patrons Helpful?

Board members often have experience in the for-profit sector that can be invaluable to dance companies. Photo via Thinkstock.

Board members often have experience in the for-profit sector that can be invaluable to dance companies. Photo via Thinkstock.

As equally important as donating funds, many patrons volunteer countless hours to dance companies. Most board members have for-profit professional backgrounds, and this experience can provide companies with insight into sustainable business models, and bring skills that artists might not have. Kirschner, for example, worked as a pro-bono lawyer for the arts when he was a practicing attorney, and filed the initial 501(c)(3) nonprofit status for EMD in 1981.

As a former commercial banker, Chapman says her skill set comes in handy when raising money for Boston Ballet: “I’m used to asking people for money—I don’t find it hard to do, especially when it’s a project I believe in!” She helped raise $3 million for Boston Ballet School’s newly constructed Newton location by organizing fundraising events and recruiting other adult students to donate.

How Can I Inspire Donors to Fund My Project?

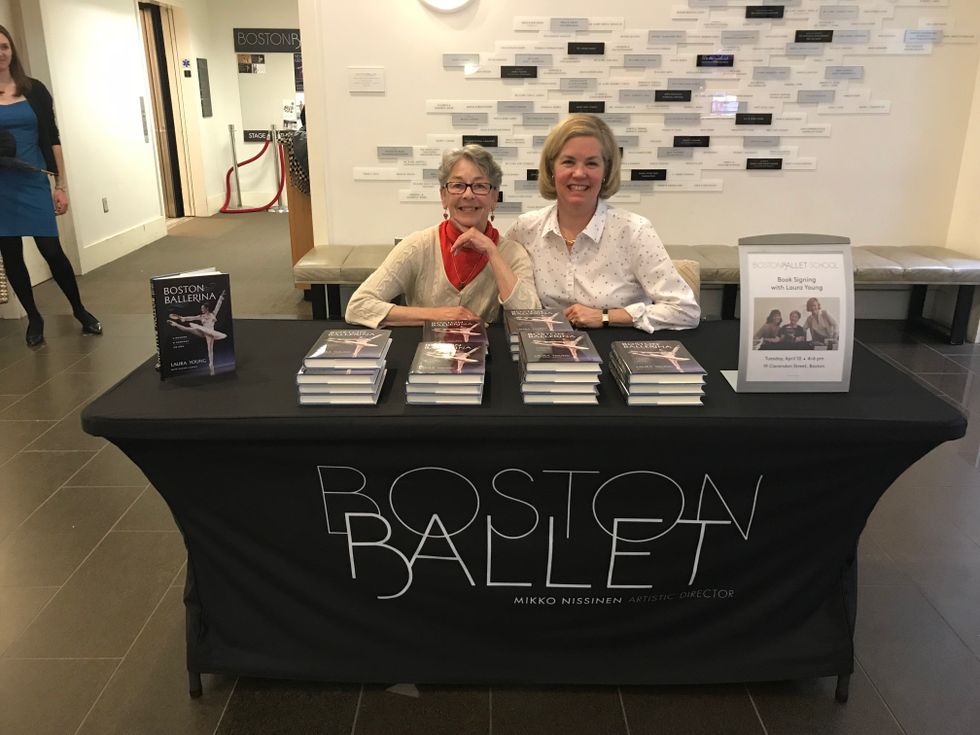

Patron Laura Chapman financed and edited former Boston Ballet dancer Laura Young’s memoir. Photo courtesy Chapman.

Patron Laura Chapman financed and edited former Boston Ballet dancer Laura Young’s memoir. Photo courtesy Chapman.

One anonymous board member of several West Coast companies tells us that she looks for an artist’s full commitment to their work before she makes a financial donation. Do they have the work ethic to warrant outside support? What is the reputation of the choreographer and their dancers? Who else is supporting the project? Is the work innovative and pushing the art form forward? Through the years, she has developed her own eye, but she does read reviews and says critics definitely have the ability to sway opinions in an art form that is often hard for viewers to understand.

Chapman prefers targeted giving towards special projects and to specific dancers or students. She funded a portion of an online archival project for BB’s 50th anniversary, and worked directly with the company’s marketing team to create a photographic timeline. She also sponsored second soloist Lauren Herfindahl while she was in the corps, and often gives towards rising stars within the school. Over the years, she developed a personal relationship with her teacher and one of BB’s founding ballerinas, Laura Young, so she financed and edited Young’s recently published memoir, Boston Ballerina: A Dancer, a Company, an Era. “I’m interested in preserving the memories of dancers, who often feel forgotten once they leave the stage,” says Chapman.