The Motion Picture Academy Celebrates Eccentric Dance

There’s a type of dance you’ve never heard of: It’s called “classical ballet.” The progenitors included Mathilde Kschessinska, Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova. The art form passed through generations from Margot Fonteyn, Rudolf Nureyev to Mikhail Baryshnikov. It continues in our own time—Misty Copeland!

It would be far-fetched, even absurd, to hear that in a lecture today! But that is how revelatory “The Choreography of Comedy: The Art of Eccentric Dance” was, at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles on August 5.

The evening program rediscovered a once-flourishing, but critically undervalued dance genre with deep historic roots. Betsy Baytos, an eccentric-dance expert and leading connoisseur of the loose-limbed, rubbery, out-of-joint, prat-fallish, snake-hipped and peg-legged, hosted and curated.

“It’s not exotic dance,” said Baytos, a former Disney animator who has been researching for 30 years in preparing a documentary. “Eccentric dance is its own unique genre. It’s a highly-skilled dancer with extreme flexibility. It’s storytelling; it’s pantomimic movement in dance. It implements a very specific repertoire of steps, and it’s wrapped around character, in a visual narrative.”

The roots of eccentric, she said, trace from prehistoric cave renderings through African and Egyptian dance; they found form and identity in commedia dell’arte clown characters Pierrot and Harlequin. Specialty ethnic dances lent flavor—Native American feather dance, Kabuki theater, Russian character dance, Celtic clogging and, importantly, British music hall. American vaudeville audiences glommed onto exotica, rude humor, caricature, ace timing and the plain bizarre. Many of vaudeville’s eccentrics, fortuitously, made the transfer to Hollywood—and Baytos has the clips.

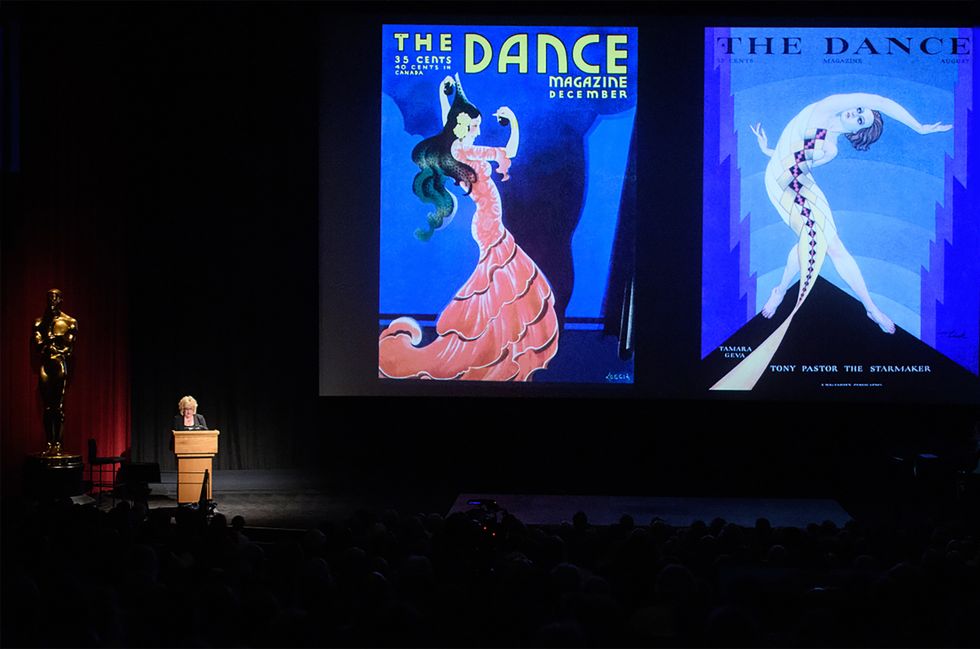

Baytos’ presentation at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Baytos’ presentation at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

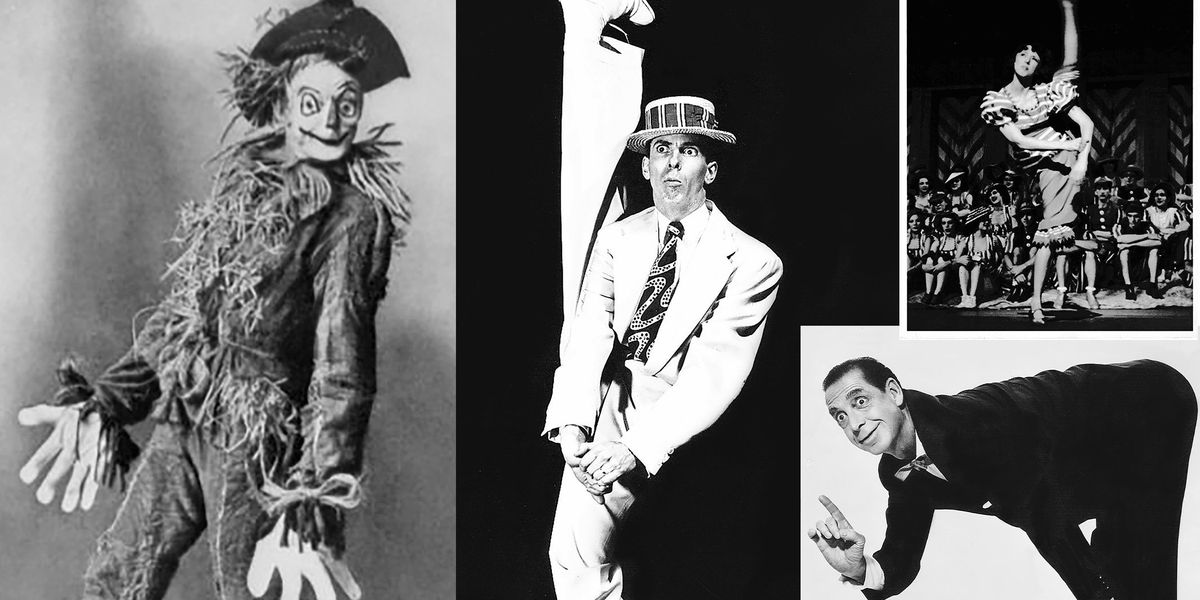

Courtesy Baytos

Monty Python relegated the stuff to the “Department of Funny Walks.” Charlie Chaplin did it with potatoes stuck onto forks, in The Gold Rush and his classic stance, a parody of the ballet’s first position. Ray Bolger stumbled down the Yellow Brick Road as a spineless strawman (and a masterful eccentric dancer). James Cagney rat-a-tat-tatted, semi-spasmodically, in Yankee Doodle Dandy. But behind those leaders were legions. A key indicator, Baytos learned from early Dance Magazines, is that from 1919 to 1934, eccentric was a regular technique offering at New York dance studios.

Shirley MacLaine introduced the event in a rare and heartfelt Academy appearance. “I identify with eccentric dance,” said the star of Sweet Charity and The Turning Point. “That’s because I was a dancer—and several people think I am eccentric.”

Simon Callow, the British actor, director and author, in remarks, said it perhaps best: “Isn’t it wonderful how weird we all are?” Performers who nearly a century ago took on monikers like “Stringbean,” “Snakehips,” “Rubberlegs” and “Butterbeans,” in new examination bear up as world-class dancers: technically gifted and possessed of a replicable vocabulary and ace comic timing. “The beauty is that it is character driven; it is very much a solo art built on a dancer’s physical idiosyncrasies,” said Baytos.

Several practitioners are well known—Ray Bolger, James Cagney, Buddy Ebsen, Josephine Baker, Red Skelton, the Ritz Brothers, Cab Calloway, Dick Van Dyke. Silent-movie comics Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Ben Blue dolloped a dose of this dance. So did later comedy legends Bob Hope, Danny Kaye and Groucho Marx. Even singers did it: Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor and Danny Kaye.

But there is also a host of unknowns: Did you ever hear of (Baytos favorites) Buster West or Hal Le Roy? What about Dan Leno, Little Tich, Dixon & Doyle, Bert Williams (the greatly successful African-American minstrel of the Ziegfeld Follies)? Al Norman’s brilliant “Happy Feet” from The King of Jazz is viewable here. Don’t forget Fred Stone (of Montgomery & Stone, he played the original Straw Man in The Wizard of Oz on Broadway), The Wiere Bros, Stump & Stumpy, The Berry Brothers. Or, “the original screwy dancer,” English-eccentric Jack Stanford.

Among the brave female eccentrics, lanky ladies Melissa Mason and Charlotte Greenwood flew in the face of “femininity” by kicking their legs, a la seconde, behind their ears. And Joan Davis, a Lucille Ball and Carol Burnett predecessor, had as her prime offering dance.

Melissa Mason dancing to Roger Wolfe Khan in 1932

Melissa Mason dancing to Roger Wolfe Khan in 1932

The fun dance evening at the Academy concurrently gave marvelous consideration to Harold and Fayard Nicholas, the consummate tap-dance team known as the Nicholas Brothers. AMPAS managing director of preservation and programs Randy Haberkamp clarified that the Nicholases “are not eccentric dancers,” although Fayard Nicholas admitted in an interview that eccentric was one of the many strands influencing the self-taught brothers.

Their signature virtuoso acrobatics and tap-dance flourishes, especially their slamming into half splits, so extreme, may border on eccentric. The best evidence that the exuberant Nicholas Brothers were far from comic dancers, but tap maestros, was on the screen in their supreme duet from Down Argentine Way.

It’s not possible to look at the cheeky eccentrics of yesteryear without thinking of breakdance, hip hop and popping and locking. Baytos sees a through line: “Eccentric is a precursor to breakdance and hip hop. We can match every move that breakdancers do to what’s been done in the past.”

Certainly today’s version of eye-grabbing dance similarly tugs the natural body into distortion, dislocation and distention. But for this viewer, a subtle but inescapable difference remains: no comic intent. We are arguably in a high moment of stand-up comedy in our culture. Why not a revival of eccentric dance?