GroundWorks DanceTheater

GroundWorks DanceTheater // Trinity Cathedral // Cleveland, OH // November 12–13, 2010 // Reviewed by Steve Sucato

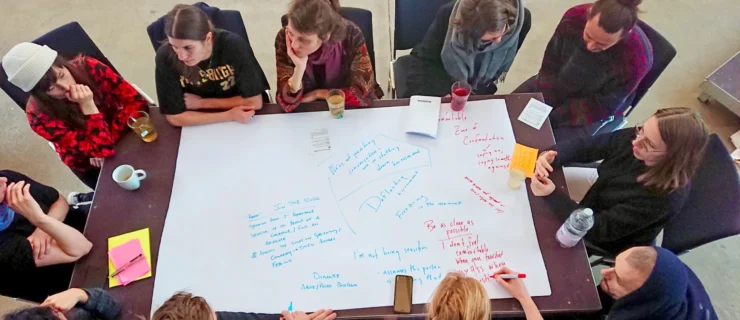

GroundWorks DanceTheater in

Just Yesterday by Dianne McIntyre and Olu Dara. Photo by Dale Dong. Courtesy GroundWorks.

A wall of gilded pipes from Trinity Cathedral’s 18th century–style great organ rose above dancer Sarah Perrett as she moved along a diagonal corridor of light as if walking a tightrope. Three other dancers joined her on the portable stage, briskly walking to collide into one another with jolting chest bumps. This opening volley of non-traditional dance movement set the tone for choreographer Jill Sigman’s new work Split Stitch.

Set to a score by composer Gustavo Aguilar, Sigman’s Split Stitch unfolded as a non-narrative collage of eclectic movement that had the GroundWorks dancers’ heads in the air, walking about smacking their lips like goldfish in search of a meal, twitching and convulsing, powering through riffs of classical ballet phrases, and popping themselves off the floor in rigid prone positions while dancer Damien Highfield shouted out counts. Despite its disparate movement phrases, Split Stitch never appeared chaotic. Through her expert arrangement of stylistically schizophrenic choreography, Sigman built tension as if holding us witness to dancers gone mad. The work concluded with dancer Felise Bagley repeatedly lifting one leg in retiré and eerily whispering the words “lovely, gently and nice” over and over.

The duet DnA, by artistic director David Shimotakahara and departing artistic associate Amy Miller, poignantly reflected on the pair’s 10-plus-year working relationship in the company. The piece revisited phrases from the pair’s prior works and touched on the emotions of their close friendship. In one moving scene, the two of them tussle and Shimotakahara blocks Miller’s forward motions as if saying to her “please don’t leave.”

The wonderfully performed program closed with Dianne McIntyre’s choreo-drama Just Yesterday. McIntyre integrated dance with spoken word and singing to form the work’s narrative, a powerful story about family and remembrance.

Set to an original composition for two guitars by Olu Dara, McIntyre’s longtime collaborator, the work’s six dancers related childhood and family stories. Recalling memories of their parents’ hobbies and favorite foods, they mimicked riding motorcycles, rubbed their stomachs making “mmm…” sounds, and engaged in horseplay like oversized children.

The work’s most riveting recollection was of Shimotakahara’s grandfather, a Japanese immigrant, whose quest for the American dream came crashing down during World War II when he and his family were forced into an internment camp. Shimotakahara’s tortured solo, danced to narration of the story and Japanese song, was chilling.