What Happens When You Bring Street Dance On Stage?

Dance Magazine reached out to us with the questions: Over the years, how has increased acceptance and visibility on concert-dance stages affected hip hop and its artists? And how has hip hop influenced concert dance?

Our response? Whoa! Acceptance? Visibility? Immediately we knew that any conscientious attempt to unpack these questions would easily exceed the maximum word count. But we also acknowledged that questions like these affect what we do as dancemakers and artist-citizens.

So we interviewed our colleague Nicole Klaymoon and mentor Rennie Harris to contribute to a conversation. We are all multilingual dance artists with our own unique voices in hip hop and street-dance theater. We are from different backgrounds and generations whose work is presented as concert dance and builds on the groundwork of Rennie Harris Puremovement.

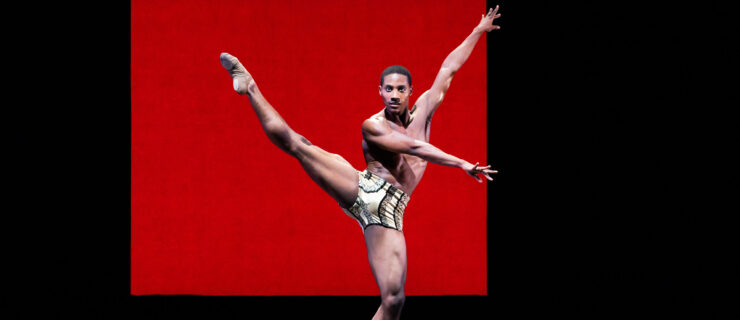

Amy O’Neal’s Opposing Forces. Photo by Bruce Clayton Tom, courtesy O’Neal

To begin, our use of the term “street dance” aims to encompass multiple dance cultures that do not necessarily identify as hip hop, yet broadly get lumped into the category of hip-hop dance. Street, club, party dances and dance forms associated with hip-hop culture have been happening on proscenium stages for a long time. We are sharing a few of our responses and asking our own questions to hopefully spark some dialogue.

On Hip Hop’s Impact On Concert Dance

Amy O’Neal:

These questions make the assumption that dances from hip-hop culture need the concert-dance world to have visibility. They have a ton of visibility outside the concert-dance world.

Rennie Harris:

Concert dance basically has appropriated everything under the sun, which has affected it in every way. So I think you have to ask, “How has hip hop not affected concert dance?” Hip hop has affected all of mainstream culture, aka white culture. It has affected the language of an entire nation when you have white kids speaking the slang.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EZ-eS-LClY&t=12s expand=1]

d. Sabela grimes:

The movement vocabulary that’s been absorbed has expanded the lexicon of non–hip-hop dance forms. I think about how the moves in breaking, for example, have opened up a gateway for fresh ways to explore the floor and multiple surface areas of the dancer’s body.

Nicole Klaymoon:

I am not an authority figure on this conversation, but I do know that when I get a job in institutions, they want to call it “hip hop,” but I call it “street” because it speaks to a community vibe and a social-dance form. So when we are innovating by taking a social dance out of context, how do you do that responsibly without disrespecting the culture?

Harris:

Ballet dancers were dancing with breakers back in the ’80s, so nothing is new. I performed with Ailey and ballet companies. We were doing this stuff way before Rennie Harris Puremovement.

On What Gets Programmed

Harris:

When you look at the scope of it nationally, how many street-dance artists are working at a high level in the theater? Not many. Although, for a while, the Hip-Hop Theater Festival was going to a lot of countries and places and giving some shine to local artists.

grimes:

There seems to be an overwhelming preference for “hybrid” work. Which usually translates to modern or contemporary with a dash of hip-hop movement.

O’Neal:

Even though there are more companies and independent artists creating work that brings hip-hop culture to the stage, the noncommercial art world is not always aware of them, nor do they know how to engage with them.

Harris:

I think if presenters know these artists, they are waiting for them to develop, but presenters are not taking these artists under their wing and helping them to develop their work.

O’Neal:

A lot of organizations talk about being diverse and welcoming of all kinds of artists, but don’t necessarily do the work it takes to connect with the constituents they claim to serve. Just because you open the doors to your castle, it does not mean all citizens will flow in.

grimes:

The proscenium is but another field of play. So, am I aware that presenting on the concert stage doesn’t validate or legitimize our dance forms, techniques and overall culture? Yes. Conversely, I’ve peeped how dance projects that encompass canonic Western narratives and dance practices are considered extraordinary and upheld as successful. Rome and Jewels and Hamilton come to mind. It’s like street culture has to keep close proximity to these signifiers of “high art” to gain greater visibility.

Don’t get it twisted. I’m not implying that it’s that simple. Nor am I saying that Rennie’s scheme was to create Rome and Jewels to gain “real” visibility. I’m one of the core collaborators. Rennie invited us in on a passion project that happened to take off. Yet having been a part of Puremovement’s previous work, I can’t help but speculate about how a Harris + Shakespeare association translates differently.

On Respecting The Culture

Klaymoon:

Is it devaluing or disrespecting the culture by bringing street dance to institutionalized Eurocentric spaces? These dances are from a place of “I’m feeling myself” in a country where there is an unseen war on people of color. We see it in the school-to-prison pipeline, police terrorism, thousands of people in Flint who lack safe water—that part of the conversation is important because that pain has played a huge role in the proliferation of these dance traditions.

When you are being exploited, you have to find liberation from within, and that is reflected in street dance. If we don’t acknowledge that subjugation of African descended people, that’s when we get into cultural appropriation. The cool thing about working in theaters is that there is space to explore and push the dance and what it can do forward.

O’Neal:

If you are a white dancer or choreographer, the way you incorporate street styles into your concert-dance work is everything. Are you facilitating space for cultural exchange? Are you working with dancers from the vernaculars that you want to fuse together? Is there reciprocal sharing of power? How will you make yourself vulnerable in the process of bringing different worlds together? How will you hold space for multiple viewpoints and experiences? How much are you willing to study physically and intellectually to stretch your own abilities to become physically multilingual, instead of borrowing a few moves here and there? Are you willing to let go of your own previously held beliefs?

If you are willing to do all of that, then we have the possibility of creating more empathy and innovation through cultural exchange in an authentically powerful way. I didn’t understand all of this when I was a younger artist.

Harris:

There needs to be a lot more space dedicated to this conversation. This is way bigger than 1,200 words.