Jovani Furlan’s Open-Hearted Dancing—And Personality—Lights Up New York City Ballet

Something magical happens when Jovani Furlan smiles at another dancer onstage. Whether it’s a warm acknowledgment between sections of Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a Gathering or an infectious grin delivered in the midst of a puzzle box of a sequence in Justin Peck’s Everywhere We Go, whoever is on the receiving end brightens.

“I could stare at him forever,” says New York City Ballet principal Megan Fairchild. “He’s just that kind of open spirit. He’s not judging anything. It’s like he’s looking at you with his arms wide open and a big smile—even if he’s not smiling, that’s the energy he’s giving you.”

Furlan was 10 years old when he started dancing at the Bolshoi Theater School in Brazil. His grandma, who watched him dance at family barbecues, had nudged him to try out when representatives came to his school looking for prospective students. “I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” he says.

Three years into Furlan’s training, Mikhail Baryshnikov came to the school when he needed to fill a gap in Hell’s Kitchen Dance’s opening act for the Joinville Dance Festival, and he selected Furlan and two girls to perform an excerpt from The Nutcracker. “That opened my mind a lot,” Furlan says. Despite no one else in his family being in the arts, that experience—and the performance footage he consumed on YouTube—led him to begin considering dance as a profession.

At 17, Furlan convinced his teachers to let him compete at the USA International Ballet Competition in Jackson, Mississippi, knowing it could lead to scholarship or contract offers. He was cut in the first round. “I felt really unprepared,” he recalls. “I hadn’t done many solos in my school, and I got there and these kids are incredible.”

It wasn’t until he was at the airport on his way home that he learned he’d been offered a scholarship to Miami City Ballet School. “Edward- Villella and Roma Sosenko were watching classes, and I guess they saw something in me that I couldn’t put onstage,” he says. “I hadn’t even heard of Miami City Ballet, but I wanted to go immediately.”

The Balanchine style’s Russian roots (“The OGs were all Russian-trained, you know?” Furlan points out) eased the transition, despite Furlan having almost no exposure to Balanchine due to the rarity of footage online. “I loved it from day one,” he says. “I was like, ‘This is how I want to dance.’ Everyone just looked so alive, moving and eating up a storm.”

His goal at the time was simply to get into the corps, which he accomplished a year later—2012, the same year the company named Lourdes Lopez as Villella’s successor as artistic director. Although he didn’t have much time with Villella, Furlan’s grateful to have started his career under him. “He wanted us to be these crazy creatures onstage,” he says. “He was interested in movers.”

After Lopez took over, Furlan continued to get opportunities, and was promoted to soloist in 2015 and to principal in 2017. “I never thought it’d happen that fast,” he says. “I was just enjoying the ride.”

Although Balanchine was all he ever wanted to dance, Furlan considered joining NYCB an impossible goal, since he knew they hired almost exclusively from the school.

But at the end of 2017, then–ballet master in chief Peter Martins stepped away from the company amidst sexual harassment allegations. The following summer saw the departure of three male principals (one of whom was later reinstated) in the wake of, again, allegations of sexual misconduct, and then that fall, the retirement of a fourth.

Furlan knew the rep was similar to Miami City Ballet’s, and he had worked with resident choreographer and artistic advisor Justin Peck, then part of NYCB’s interim leadership team. “I just saw this open window,” he says. At Miami, “I had everything. I knew I was a favorite. But I wanted to fulfill my dream of dancing at Balanchine’s house.”

So, at the beginning of 2019, he emailed Peck. “I asked him to let me know if they were ever open to hiring someone from the outside, that I would love to try out—a year from now, five years, whenever.” Peck passed along the message, and Furlan auditioned that very week.

“We had heard from Justin that Jovani was an excellent partner, and we were looking for a young male dancer with experience dancing principal roles,” says NYCB artistic director Jonathan Stafford. “Jovani clearly had a good grasp of the Balanchine aesthetic, and he was also a strong, athletic dancer. He immediately came off as very friendly and respectful.” Two weeks later, Furlan was offered a soloist position.

Furlan hit the ground running that fall. “The rhythm of the work was shocking for me,” he says. The sheer difference in the volume of repertory—the dancers are contracted for the same number of weeks, but NYCB does 54 ballets a year to around a dozen for MCB—meant Furlan had to adjust to having far fewer rehearsals for far more ballets and performances.

He was onstage sooner than he’d anticipated. His name appeared on the casting for the first week of the fall season: Christopher Wheeldon’s DGV: Danse à Grande Vitesse, with Megan Fairchild—with whom he had never rehearsed, for a section of the ballet he had not been called to learn. Then another dancer got injured, so rather than making his NYCB debut at the end of the week, he was moved up to a Wednesday performance with Ashley Bouder.

“I remember going home and filling a suitcase with whatever I could find and running the pas with the suitcase,” carrying it and lifting it as though it were his partner, he says. “I was freaking out. I needed to make sure I could get through it!”

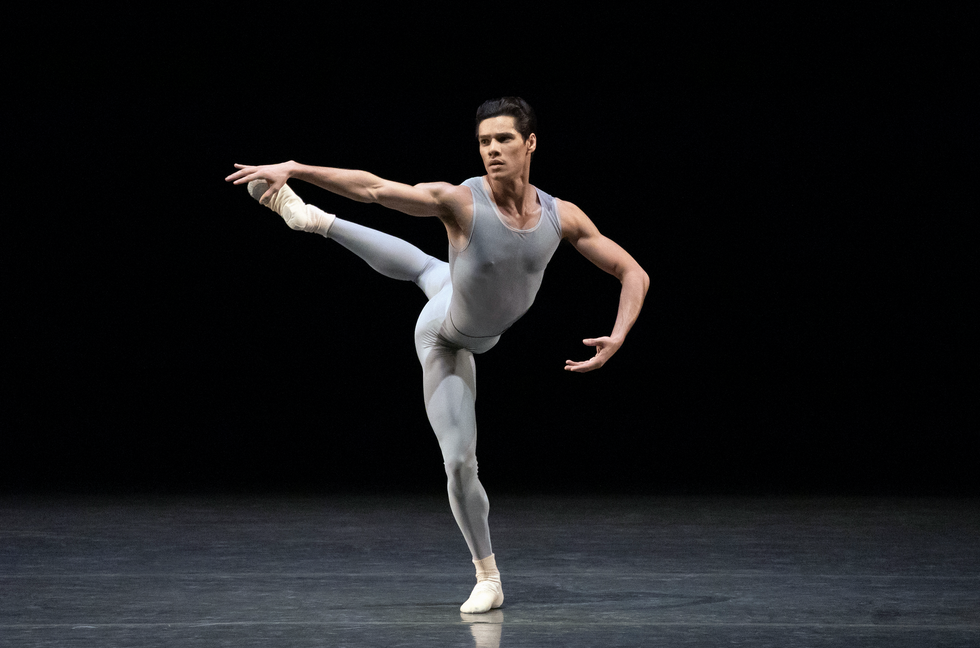

Concertino Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Everywhere We Go. Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Episodes. Erin Baiano, Courtesy NYCB

Fairchild, now a frequent partner, muses that NYCB is a hard company to enter as a soloist. “We juggle so many things compared to other companies, and we have this bond of SAB and being in the dorms together,” she says. “Someone can come in and just not understand the culture. You can step on a lot of toes accidentally. I think it takes a person like Jovani. There’s nothing you can find wrong with him. He’s one of the happiest, smiliest guys I’ve ever met.”

When they did Wheeldon’s Polyphonia together, Furlan would whisper the complex counts to Fairchild. In Everywhere We Go, he’d remind her of which set of steps was next. “I’ve never had a partner do that before,” she says. “It’s incredibly refreshing to be in rehearsal with someone who’s done his homework. He’s incredibly organized.”

Furlan was far busier in his first season than Stafford anticipated, “but we ended up giving him more and more repertory and he responded with flying colors.” Fairchild remembers trying not to let on just how challenging or overwhelming dancing certain ballets might be when Furlan would share his schedule with her. But, “he’s only been impressive,” she says.

Furlan’s morning and postshow routines have shifted in response to the workload. He already had a cadre of physical therapy and conditioning exercises to keep his body balanced, and had taken up meditation and gotten certified as a Reiki practitioner before his move to New York City.

During last year’s Nutcracker season, a friend introduced him to Kundalini, a branch of yoga practice which focuses on intense breathwork while holding relatively simple poses for challenging lengths of time. “The first two weeks I went nine times,” he says. The centeredness he gains from it helps him manage the chaos of performance season. “The load—mentally you have to be really calm, to just go with it,” he says. “My last week, I did eight shows, five different ballets. I didn’t think that was physically possible.”

To recharge during his rare downtime, Furlan takes long bike rides before finding a spot by the waterfront or in Central Park to sit with his Kindle. (“I love love stories,” he says with a smile.) He’s now conversational in French, thanks to his nondancer boyfriend—a Frenchman with a corporate job—and wants to find time to see more musicals once Broadway is back in action.

“He’s always trying to learn something,” says Peck. The choreographer drew on that energy when creating Furlan’s role in Rotunda, a ballet about making a ballet. “I remember literally giggling onstage on the premiere,” Furlan says. “I don’t think I’ve ever felt that happy onstage.” That joy was palpable from the audience as he giddily skipped past Brittany Pollack after gently landing her from a lift, or half-closed his eyes and let gravity take over as he disappeared into the music’s current.

“Whoever is put in front of the room with me, whatever I’m working on is my favorite thing,” Furlan says. With characteristic enthusiasm, he can’t quite pick a favorite of his NYCB performances so far. There’s Everywhere We Go, opposite Fairchild, and Balanchine’s Kammermusik No. 2. He also mentions the Paul Taylor–originated solo in Episodes, which he had learned from Peter Frame and for which Furlan helped coach former Taylor star Michael Trusnovec, an experience that sparked an interest in someday acting as a Balanchine répétiteur.

That voraciousness, that openness, animates Furlan’s dancing as well as his presence in the studio. It seems to be an attitude that will continue to serve him and NYCB well after the curtain goes down, according to Peck: “He’s shaping the overall feel of the company.”