#DancersToo: Is The Dance World Ready To Address Sexual Harassment?

When an anonymous letter accused former New York City Ballet leader Peter Martins of sexual harassment last year, it felt like what had long been an open secret—the prevalence of harassment in the dance world—was finally coming to the surface. But the momentum of the #MeToo movement, at least in dance, has since died down.

Martins has retired, though an investigation did not corroborate any of the claims against him. He and former American Ballet Theatre star Marcelo Gomes, who suddenly resigned in December, were the only cases to make national headlines in the U.S. We’ve barely scratched the surface of the dance world’s harassment problem.

One reason why: The same culture that makes harassment possible in dance makes it uniquely difficult for artists to speak up.

Where It Begins

The problem starts with the way we train dancers: “The dance world has held on to a pedagogical method that disempowers the dancer before sexual abuse would even occur,” says Robin Lakes, a University of North Texas professor whose research focuses on dance pedagogy.

Dancers are taught not to question those in roles of authority. Photo by Jon Tyson/Unsplash

Dance training can create an environment where students depend on teachers for validation and are taught to accept any rules or roles they’re given without questioning them. The extreme power differential that often exists in the classroom usually doesn’t change much once dancers reach the professional level, where directors can single-handedly decide a dancer’s fate and powerful choreographers can get away with inappropriate behavior.

While it’s easy to blame the physical intimacy of dance jobs for sexual harassment, power dynamics and working environments are the bigger culprits.

What Harassment Looks Like Today

Although, so far, the dance world’s most prominent examples have come from large ballet companies, harassment can happen within any genre and at every scale. In fact, the increasingly freelance nature of the field makes artists especially vulnerable.

Catherine Drury, a licensed clinical social worker for The Dancers’ Resource at The Actors Fund, points out that having multiple employers or sporadic work can leave dancers unclear about what their rights are, who they should report to and what protections are in place. Institutions are responsible for providing a safe and harassment-free workplace; however, some might not take freelance artists fully into account when developing policies.

For instance, an anonymous New York City–based performer and choreographer told Dance Magazine that she was sexually harassed during her time as an artist in residence at a prominent dance theater. The photographer who shot her piece, an independent contractor hired for the season, asked her to come to his apartment to review and purchase photos, where he touched her without her consent and verbally harassed her. Because there was no procedure for how freelance artists should purchase photos, the harassment occurred off-site and without witnesses. At the time, the institution’s sexual harassment policy did not apply to independent contractors.

As dance evolves into new spaces and contexts, action around sexual harassment needs to evolve with it. A recent BuzzFeed News story reported 17 incidents of groping or sexual misconduct by patrons of the immersive show Sleep No More. Audiences, who are masked for the entirety of the performance, are encouraged to buy alcoholic drinks, but have traditionally not been told to refrain from touching performers or given parameters regarding acceptable behavior. Cast members are sometimes naked and at other points are alone with a single audience member.

Sleep No More

isn’t the only immersive production that’s dealt with harassment. Contemporary dancer and choreographer Kate Ladenheim performed in an immersive show where she was physically and verbally harassed by audience members. When she spoke to her artistic team about the incidents, they took her feedback and worked together to address the situation so performers felt safer in the role.

“I think that immersive theater as a genre thrives largely on exoticism and heightened sensuality,” she says. “This expectation can lead audience members to think they have permission to play around with performers.” Today, when Ladenheim produces her own immersive-like events, she makes it clear to audiences that they will be removed without a refund should they touch a performer.

Kate Landenheim has written agreements with her dancers that cover safe rehearsal practices. Photo by Keira Chang, courtesy Landenheim.

What’s Onstage Matters

The content we see onstage can perpetuate—or reflect—a culture of sexual harassment. Last May, Siobhan Burke wrote a story in The New York Times titled “No More Gang Rape Scenes in Ballets, Please,” in response to Alexei Ratmansky’s Odessa for New York City Ballet. Many responded with similar reactions, while others—including Odessa cast members—argued that there was no such scene. The debate also touched on the issue of censorship: Is there a way to depict sexual violence onstage that isn’t problematic?

As often as women are oversexualized and their characters abused onstage, few choreographers intend to normalize sexual harassment in their work. Still, that doesn’t make their depictions any less harmful.

Contemporary choreographer Brendan Drake works hard to make art that reflects his values. But at a showing of his work, someone pointed out that one of his pieces—which featured women in red lipstick, tight vintage dresses and thigh-slapping—could be interpreted as misogynist. He changed the piece, then eventually decided to scrap it altogether. To avoid putting unintentionally sexist or unnecessarily violent work onstage, he suggests that dancemakers continually question how each of their choreographic choices serves the work, and get feedback multiple times before formally presenting it.

Brendan Drake evaluates his work for unintentionally sexist themes. Photo by Theo Cote, courtesy Drake.

We Can Do Better

Much of what are considered best practices in other fields don’t easily apply to the dance world: Corporate sexual harassment training may instruct employees to avoid touching one another and to wear modest clothing. Standard policies don’t take into account the unique demands of dance. And creating rules around affirmative verbal consent in the studio can feel at odds with dancers’ ability to communicate through their bodies with intention and nuance.

So what would dance-specific policies look like? As Boglárka Simon-Hatala, a physiotherapist and health sciences teacher who works with dancers, points out, we need more research around how sexual harassment plays out in the dance world to thoroughly answer this question.

But we do know some of the factors that make dance artists vulnerable: The extreme competition in the field can lead to a culture where harassment is tolerated for fear of losing a job or being black-balled. The importance of informal networking, the irregular working hours and the frequency that dancers travel with co-workers can lead to blurred lines. Dancers are often relatively young, and their short careers create added pressure to tolerate poor treatment or stay in an unsafe environment. We need strategies that address these challenges head-on.

Extreme competition can drive dancers to settle for poor treatment. Photo by Kate Williams/Unsplash

The real onus for preventing sexual harassment lies with institutions and their leaders. Clear policies that encourage reporting inappropriate interactions should be widely distributed. Everyone—especially those in leadership positions—should undergo harassment training that is specific to their role. Response to claims of harassment should be proactive, not reactionary; compassionate, not defensive.

Finding chains of accountability—even within small companies or projects—is also key. Since being harassed by the photographer, the anonymous NYC-based artist has considered implementing a system through which all collaborators would be held accountable via the institution they’re working with. Contracts with all parties would stipulate that the collaborators could go to the institution should any issue arise, and it would then investigate and mediate the situation.

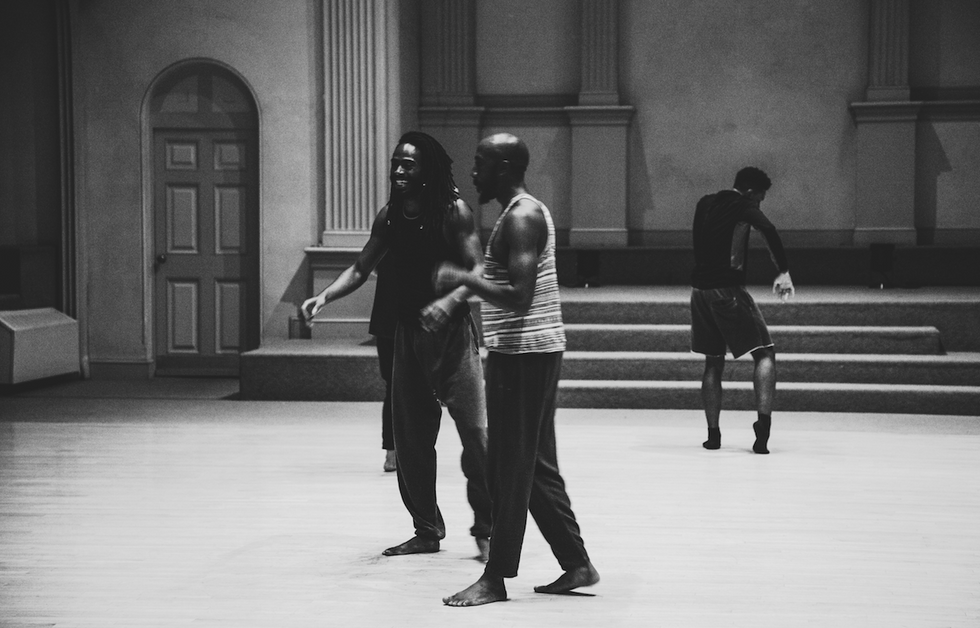

Ladenheim has carefully crafted written agreements with all her dancers that discuss their safety and encourage them to express their discomfort if any explorations in rehearsals go too far. Similarly, performer and choreographer Ricarrdo Valentine has daily check-ins, both one-on-one and in groups, with his dancers about their physical and emotional boundaries. He emphasizes that these can shift daily—what’s okay one day may not be the next—and that even as dancers, having a practice of verbal consent around physical contact is essential.

Ricarrdo Valentine checks in with his dancers daily. Photo courtesy Valentine.

Another strategy for institutions could be decentralizing power. For example, NYCB’s appointment of four interim leaders to replace Peter Martins means they must at least be held accountable to each other. While it’s unclear how long this setup will remain, there have been outside suggestions of breaking down the ballet master in chief position into multiple roles.

Of course, who is filling these roles is what matters most. We need leaders dedicated to equity and accountability. We also need more women in positions of power: Researchers have found that male-dominated organizations are more prone to sexual harassment.

Though it can feel like a daunting challenge, numerous studies show that companies whose leaders believe that harassment is wrong and convey a sense of urgency in preventing it have less harassment. Yes, organizations should have clear and specific policies, safe working environments and thorough training. But they also need leaders who care. It’s not going to be an easy fix, but it’s what the dance community needs.

Where to Turn

Resources for preventing and reporting sexual harassment in dance:

-

For educators:

Youth Protection Advocates in Dance‘s certification program includes topics like sexual abuse and sexualization in dance. -

For help reporting harassment:

Better Brave

provides a template and guidelines for taking action. -

For counseling:

The Actors Fund

has social workers on staff who can speak with you about your experience and help you explore your options. -

For legal assistance:

Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts provides pro bono legal work for qualified artists. -

For additional resources:

Visit Dance/NYC or Dance/USA online.