Discovering a Whole New Misty Copeland

In the middle of one of New York City Center’s cavernous studios, Misty Copeland takes a measured step backwards. The suggestion of a swan arm ripples before she turns downstage, chest and shoulders unfurling as her legs stretch into an open lunge. She piqués onto pointe, arms echoing the sinuous curve of her back attitude, then walks out of it, pausing to warily look over her shoulder. As the droning of Ryuichi Sakamoto and Alva Noto’s mysterious “Attack/Transition” grows more insistent, her feet start to fly with a rapidity that seems to almost startle her.

And then she stops mid-phrase. Copeland’s hands fall to her hips as she apologizes. Choreographer Kyle Abraham slides to the sound system to pause the music, giving Copeland a moment to remind herself of a recent change to the sequence.

“It’s different when the sound’s on!” he reassures her. “And it’s a lot of changes.”

The day before was the first time Abraham had seen Copeland dance the solo in its entirety, and the first moment they were in the studio together in a month. This is their last rehearsal, save for tech, before the premiere of Ash exactly one week later, as part of the opening night of City Center’s Fall for Dance festival.

They’d started working during Copeland’s spring season with American Ballet Theatre, “literally the busiest time of my entire year,” she says. “Throughout my spring season, I was going in on Sundays, my only day off, and working with Kyle. It’s really difficult when you have several ballets in your brain that you’re trying to digest and prepare, and then you’re adding more!”

Because of their equally packed schedules, the gaps between rehearsals were often measured in weeks rather than days. Abraham had to create sections of the piece on members of his company, A.I.M, who then transmitted it to Copeland. “It was so exciting to be in the studio with them,” she says. “I was telling Kyle, Because of who you are as a person, you surround yourself with incredible dancers. They move so well, and in a way that is totally different than what I’m used to.” (She got to spend more time with them when she reprised Ash for the opening night of A.I.M’s Joyce Theater run later in October.)

The pairing is the sort of starry, worlds-colliding event FFD relishes—arguably the most recognizable ballerina in the U.S. and a MacArthur-certified “genius” choreographer who has described his vocabulary as “postmodern gumbo.”

Though he’s worked with his fair share of respected dancers, Abraham admits, “I have been a fanboy for a very long time. I got Misty to sign my copy of Dance Magazine with her on the cover years ago!”

They began, as Abraham prefers when working with someone new, with two phrases he had prepared. “I have no desire to make people look like me,” he says, “but when I’m working with dancers from different disciplines, I’m interested in seeing how we can either create our language together or have a conversation with our differing languages in a way that’s complementary.”

He sees this piece as a bridge for them both—in his case, one that might temper preconceptions that could pigeonhole his work after his boundary-breaking success with The Runaway at New York City Ballet last year. “I don’t want people to ever come to my shows and know what they’re going to get,” he says.

For Copeland, that’s ideal. “At this moment in my career, I’m working with people that will push me beyond what people expect of me,” she says. “I’m not looking to ‘be Misty’ onstage.”

And though Abraham started with things he—and an audience—loves to see her do, he was also “trying to address potential assumptions about what the work would be,” he says, “and allowing those conversations about expectations to really fuel how we treat the movement.”

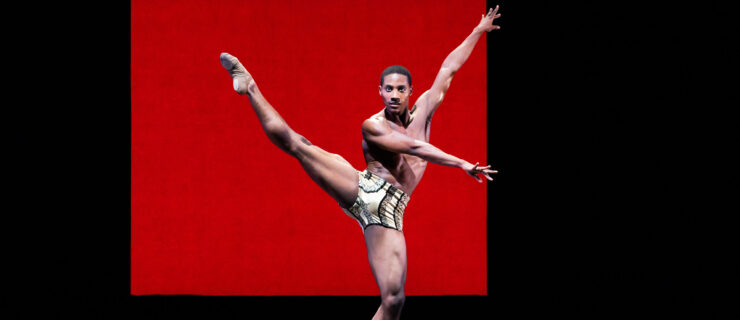

In Ash, there are certainly steps with French names—Copeland fires out saut de basques, piqué turns and a développé or two. But freed from the requirement to be light and airy, and paired with an upper body that alternately lags behind or redirects a sequence, the ballet steps gain new intensity. Petit allégro rhythms seep into the spinal undulations and fluid, counterintuitive pathways common to Abraham’s vocabulary.

“To get comfortable with the movement language, and with voicing your opinions, all of that stuff takes time,” Abraham says. “We’re just getting to a place now where there’s room for us to go deeper.”

At this final rehearsal, Abraham is cutting out snippets of phrases, asking, “What is necessary? What is frivolous?” and then working with Copeland to make sense of the gaps. “We all know that she’s a diligent worker,” he says with a grin. “So at this point, I’ve given her homework.”

Abraham’s notes are often framed as questions, which Copeland answers with questions and solutions of her own. There’s laughter on occasion—Abraham jokes about his “biscuits.” But for the most part, they share an outwardly calm focus.

“We’re both introverts,” Copeland says. “I feel that’s a commonality that drew me to Kyle. His work speaks for itself.” When asked whether he wants to expound upon the solo’s title, for example, Abraham demurs with a laugh. “Why do people need someone to always tell them what something means? It’s dance, people! Maybe there’s meaning, maybe there isn’t, but you are free to think as you so choose.”