Emerging From the Pandemic With an Epic Marathon Solo

In late 2020 I was on the phone with Heidi Latsky, whose New York City–based company I’ve danced in since 2007, batting around ideas of what we could do that would be ambitious, outside-the-box. With a deep breath and a not-small dose of chutzpah, I shared with her the idea that I’d been sitting on for a good year or so, one that was particularly preposterous given that I was entirely out of shape at the time, 10 months into the pandemic. I told her that I wanted to do our evening-length endurance trio, Unfinished, as a solo; that the tracks of the three original cast members (Jerron Herman, Jillian Hollis and me) all felt like three aspects of one personality; that it could be compelling for one person to do all of the group sections and all of the solos, even the ones that were crafted specially for the other dancers. She loved it.

The loose plan was that maybe, just maybe, I’d start playing with it in May, after Heidi Latsky Dance completed our eight-day bubble residency for Montclair State University’s PEAK Performances series, and we’d see where it went.

Well.

The day after we returned from being sequestered, a gig materialized, and Heidi offered me the biggest opportunity I’d yet received, which would mark my return to performing in front of living, breathing humans. On June 13 I would be dancing a reimagined version of Unfinished—as a solo, outdoors, on the land once occupied by the Lenape that was referred to as “Kintecoying,” or “Crossroads of Three Nations,” currently known as Astor Place in Manhattan, on artist Rashid Johnson’s Red Stage—as part of a monthlong festival produced by Creative Time.

My dear friend Jillian Hollis would also present her version of the solo right after me.

The producers threw us a curveball. For zoning reasons, this 50-ish-minute dance would have to be done in silence.

Unfinished

was originally made in 2018–19 to look abstractly at the rituals we use to try to push away death. I interpret it slightly differently, that it is more about the postapocalyptic questions of How do we go on? And what might that look like in the aftermath of such trauma? What does it mean to be “unfinished”?

Author Meredith Fages in the original version of Heidi Latsky’s

Unfinished Beowulf Sheehan, Courtesy Fages

Early on in the pandemic, I asked a friend: “What if I’m not a dancer on the other side of this?” I ached when I spoke those words aloud. My husband and I have a young child, and during quarantine, we were doing what felt like too much and never enough to try to keep ourselves steady. The only dedicated time I had to dance was at 7:30 am, while the coffee brewed.

Although I performed a solo for virtual outlets twice, once from the living room and once from a beach, I wasn’t part of what appeared to be a seamless pivot for so many in the dance community. I opted out, by choice and by necessity, which didn’t come easy. I’ve been a devoted-sometimes-obsessive class taker throughout my career. Dancing at home gave me shin splints, a twisted ankle and a whole host of cascading alignment problems. I’m a jumper, and that didn’t translate well to an in-home practice. To say nothing of the absence of rehearsal and live performance, the loss of studio class was another kind of death.

I’d like to say that I was graceful about it, even when I was quiet about it, but that wouldn’t be quite accurate. I tried not to complain. I had a roof, family, food and my health. However, as the pandemic stretched on and on, and my morale sank lower and lower, I started to feel like I really was finished. I was 42 at the time. Was this it?

On January 1, 2021, I made the commitment to myself that I had to start moving again, even if it wasn’t in the same ways that I was used to. I found the Gaga online-class community, which proved to be exactly what I needed in terms of a sweaty shot of daily endorphins. In the spring, when COVID-19 restrictions in New York City started to loosen, I was able to rent studio space occasionally for short bursts of time to work by myself, whether with some sort of class that I gave myself, or a video from Dancio, or improvising in an undefined genre. I wasn’t in the same shape, but I was in some shape, even though I couldn’t allow myself to think about that or anything about the future too hard (for once). It helped.

Then the solo opportunity landed in my lap. With one entrance at the beginning and one exit at the end, I’d be dancing pretty much nonstop. In my experience of the trio version, the only way to mentally and physically tackle this piece—a dancer’s dance—the way it needs to be done is to run it. I did just that, five days a week for six weeks, until the performance.

May 3, Day 1

6 train to the F, Brooklyn-bound. I’ve lived in New York for more than 25 years, but my subway skills are rusty. I stand in the wrong place; I don’t know which way to go for the transfer. Someone pulls the emergency brake. I am uncharacteristically sanguine. I’ve waited so long for this; what’s 15 more minutes?

I emerge into bright daylight, feeling the thrill of having left my neighborhood, which I haven’t done very much lately. I’ve been to Open Arts Studio, choreographer Laura Peterson’s new space in Brooklyn, once before, shortly after it opened in April. There is a mosaic tile medallion on the floor of the lobby of this converted factory that reads “Grand Union,” in reference to the tea company whose headquarters were housed there from 1915–28, but it means something else altogether to a dancer working in a postmodern lineage!

I improvise the choreography of getting set up in a new place, with all of the COVIDerie, like air purifier, fans, wipes, windows, air conditioning, connecting the phone and laptop to Wi-Fi. The red oak floors are freshly lacquered, and the brick ceiling arches, scraped of their original paint, offer yet another sense of history to the space.

The light is gentle. My feet are softer.

I’m working alone this week. I watch the same phrase over and over again to reconstruct the intricate movement from two performance videos, on mute. It’s slow going, but I get through a few sections.

May 4

My muscle memory is dormant.

To revive it, I start toward the end of the piece, with footage from the final group section. Sound on, one time only. This is the one section where we used to come together, in a celebration of sorts, as opposed to dancing as soloists in unison. There is flow and freedom in this movement that is purposely absent in other earlier sections. I think of Jodi Melnick costumed in silk, with her hybrid of influences from Trisha Brown and Twyla Tharp, when I dance my movement that begins the section. My eyes well up. I miss Jerron and Jillian.

The original audio score was a quilt of new music and old. Heidi often repurposes music within her repertoire, and we also work pieces for a long time. Layers of memory are constantly regenerating, bringing remembrances of things past, whether dancers, dances, process or production stories, right back into the present. This iteration of this dance, particularly as it relates to COVID, and all we’ve lost, feels like dancing with ghosts. However, I don’t want to show something that is less-than. I carry all that has come before this moment, lovingly, and now I need to look forward.

I decide not to use the score anymore in rehearsal. The dance needs space to emerge into something other than what it was before.

May 10

Location change. I’m in Times Square, at New 42 Studios. I’ve rehearsed and performed in this building for over a decade. You never know which theater or dance luminary is going to be in the elevator when the doors open, but on this day, I think I might be the only person in the building other than the staff. It’s pin-drop quiet. Large squares of dusty, brown particleboard are taped over the wood dance floor for reasons unclear to me. The air conditioner whirs softly as sunlight floods through the floor-to-ceiling windows.

The marquee for Lion King across the street flashes “THE WAIT IS OVER.”

Courtesy Fages

I give myself a quick barre. The ballet music I’ve been using the most since the pandemic started is played by Josu Gallastegui, but this particular CD is aptly titled Return Engagement.

I try out my first pair of new dance sneakers. Fail. They don’t work at all. Unfortunately, I can’t make this assertion until I’ve worn them to dance for an hour, by which point they’re scuffed and I won’t be able to return them. I’ll have to try a different pair tomorrow. There’s a lot of sliding, with deep chassés into second position grand plié, for which I need to be grounded, and lateral stability is problematic. I’m slipping all over the place, and I’m losing sensation in my fourth and fifth toes. I’m annoyed. I don’t want to wear shoes at all, but I also don’t trust that a fire-engine-red metal floor for a late-morning matinee in mid-June will be safe for bare feet.

May 11

The enormous simulacrum of Jennifer Lopez’s face stares provocatively at me from across the street at Madame Tussauds.

Heidi’s coming in today. She asked me to bring in an outfit. We’d decided that the original costume was not appropriate for this venue or context. Jillian constructed the original costumes, which gave the illusion of being unfinished. They were built on muslin, with raw hems, loose threads and asymmetrical patches of lace in tea-stained ivories and tans. I’d had a dress with beautiful flow and line, but it’s the wrong aesthetic for the slog of the pandemic, daylight, sneakers and a red stage. Heidi suggests something athletic, like black rehearsal clothes. I offer my favorite dancing shirt, a flowy, asymmetrical slub-knit short-sleeved shirt, black shorts, white kneepads and a different pair of dance sneakers that are dusty-pink suede. She approves, and I exhale. Self-costuming gives me agita.

“Well, what do you want to do?”

“I guess I should run it.”

Breathing efficiently is a challenge. I am masked for rehearsal indoors, even though I won’t be for the performance outdoors. I channel runners training at altitude. My face is the color of Heidi’s mulberry shirt, but I get through it—well, even. Afterwards, she reminds me to “take a walk” instead of melting to the floor, as she was once reminded by Molissa Fenley (of endurance-solo fame). In its new form, the dance works.

As I leave, I salute the placard on a garbage can on the sidewalk across from the lobby doors that displays a quote that says it all, from Laurie Anderson and A.M. Homes: “Embrace the absurd.”

Courtesy Fages

My long-time ballet teacher Nancy Bielski teaches to the tenet that “your dancing must have a musical point of view.” How does that carry over when there is no music? I translate that as a rhythmic point of view. We built several source phrases in 7s instead of the more traditional 8s. Conceptually, this helped to establish the dramatic friction of being unfinished.

All of the information for the audience has to come from my execution of the choreography, which, for Heidi, is always task-oriented. It might be evocative, but it is never emotive. We talk about the importance of clarity of the rhythm and tempo, and how to refine movement dynamics, like energy and weight, for each section. There is so much repetition in this piece that these qualities must be like a map for the audience (and not a sedative) that allows the abstract, non-narrative arc to evolve. Rhythm, tempo and repetition serve as conduits for a sense of memory and the blurring of time. Each section of the dance is a ritual of its own, and by the end, we have something that is greater than the sum of its parts.

The introductory section is essentially a moving meditation with a lot of counting and repetitive choreographic structures that warm up different parts of the body. When we made it, we used to text notes back and forth to each other that read something like “5-7-3-6 5-7-3-9 5-7-3-6 6-3-3-9.” That’s about one minute of choreography in a section that’s 15 minutes long.

Following that section, I stop at the center mark in first position, with my arms directed down by my sides, palms facing forward and head gently bowed, to reset for a few deep breaths in stillness before going right into the section that has always been my solo. There used to be a dramatic lighting shift from dim sidelights to a stark, tight spotlight from above that trapped me like a cage. The music was a lush, sweeping piano solo by John Bayless that was his first composition after recovering from a stroke that left him with the ability to play with one hand instead of two. The movement is lightning-quick, with nonstop changes in facing, and I never leave the center mark. To convey the right tension in the absence of lighting and sound, this section that was already fast now needs to be even faster, more agitated. It’s as though I am ahead of the beat as opposed to being on top of the beat, but I have to do this without getting physically ahead of myself (ribs protruding front, pelvis behind), like I’m dancing in fast forward.

May 13

This dance was originally made for a wide, rectangular stage, or what I jokingly call a “stage-shaped stage.” Red Stage, however, is a trapezoid, and not as wide as past venues. We need to adapt accordingly.

I set up corners of the trapezoid with my track jacket, pants and street shoes strewn about, while Heidi pops off an email to the building coordinator to ask if we can use painter’s tape to demarcate the space. Merely imagining the diagonals of the trapezoidal stage, particularly over the grid of particleboard, is slowing down my navigation. If I could just see the lines, I could make clearer and faster decisions. I also think about former company collaborator Krishna Washburn, who is visually impaired, wondering what other strategies I can draw upon that don’t privilege sight. The spatial geometry of this formalist dance is intentional, and it is showcased in the two sections that follow the warp-speed solo. They used to be group sections. I will execute my patterns and Jillian will execute hers when we each perform, but they are not the same.

The tempo shifts to moderato without getting soft or airy for the next section, which we call “Merce” for its erect posture and linearity. There’s no Cunningham choreography in it. There is, however, a lot of ritualistic repetition of the 7s and of the longer choreographic sequences that they form. I must be squarely and consistently in the center of the silent beat for the duration of this 15-minute chunk. The traffic patterns involve lateral passes and diagonals that remind me of Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, and also of the paintings that Laura Peterson made as sound baffles for Open Arts Studio.

The beat of the walking pattern that ends “Merce” is interrupted by a new energy that propels me through the section we refer to as “Animal.” The geometry is just as visible, but the dramatic tension increases with the introduction of mixed meter, a faster tempo, my weight shifting forward like a panther. This section evokes that stage of percolating rage when your jaw sets and your body gets hot, the moments right before you blow up.

Today Heidi works with me to integrate my front body into my back body. I have a brachial plexus traction injury that I’m protecting, and as a result, my body is having a hard time finding verticality. I look like a bobblehead.

She suggests that I work with a singular physical focus today, as though someone were pushing my pelvis from behind. It borders on tucking, and it usually feels pretty hideous when I get that note. Initially the range of movement feels compromised, but, with practice, it starts to make sense in my body. My alignment becomes more integrated. I can see in the mirror that I look more powerful. I can read as light or flitting, because of my speed and ballet training, and we work together to make me more grounded and primal, which are qualities inherent in “Animal,” in particular. Jillian embodies these qualities more naturally. She is a luxurious, voluptuous mover and a powerhouse performer. We learn a lot from each other.

As we head to the elevator, we smile when Heidi says, “This is a pleasure.”

May 17

I’m downstairs in the cave studios at New 42 this week. Windowless, with buzzing fluorescent lights. The floor is covered in marley instead of particleboard, but it’s slick and my sneakers are slipping. I’m stiff. Metaphorically, this environment feels emblematic of COVID.

For this run, my pacing is blown. Heidi points out afterwards that I never downshifted for “Merce.” I’d gotten stuck doing something like 35 minutes of material at the same rate and with the same movement dynamic, and it was wrong. No wonder I feel like I’m going to hyperventilate. The pacing for a dance performed by three people is necessarily different from the pacing for a dance to be performed by one person, but this was not it. It was an important mistake to make. Once.

May 18

I go over the opening revolving motions a lot. These first movements need to establish the right rhythm. I think I have a pretty steady internal metronome, and yet I’m reminded of an exercise that Mark Morris offered in a workshop I took ages ago: to close your eyes and raise your hand after you count 30 seconds. Everyone in the group was wrong.

May 19

As I start to run the dance, I remember how Donlin Foreman, my Graham teacher from college, used to say that sometimes people just turn up the music instead of deepening in the choreography.

With that in mind, I spend some extra time afterwards on the section formerly known as “Jillian’s Solo,” which follows “Animal.” It’s floor-based, minimal in movement but maximal in power. I cried in the wings every time I watched her perform it. Heidi had asked Jillian to draw on some deeply personal—and emotional—experiences when they were originally developing that choreography, which was juxtaposed with a Handel aria. It’s like the stage of grieving where you can barely get up. But if Jillian emoted or even cried while she was rehearsing it, it didn’t work. Comedy, for example, is a lot less funny when the performer is laughing. Like all the other sections, particularly “Animal,” this one has to be perfectly calibrated, even restrained. Task-driven and nothing more. I need to be able to hit the same notes myself, stripped of the sound, while maintaining the pacing and without suggesting a false ending that could cause the remaining sections of the piece to tank.

I used to be afraid of my own stillness onstage. Then I read a review by Joan Acocella in The New Yorker years ago, in which she articulated how the most riveting performers don’t have to do much of anything at all, yet you can’t take your eyes off them. I aspire to this.

May 28

This is a banana dance. I have to eat one 20 minutes before I run it, and I drink nearly a gallon of water after it. At some point during the run, alone, dripping, I have to laugh aloud at why I’m working this hard when there’s no one else in the room.

June 3

In my morning Gaga class online, Saar Harari offers the cue “Cancel your resistance.” I like this. Of course, there are times that resistance is useful, but many times it just isn’t.

June 7: Week of show

I’m a racehorse at the gate. I’ve felt ready to perform for a week and the show isn’t for another six days. It’s tough not to check out, like this is a rote task that I’ve memorized. If I do that onstage, the piece will fall flat.

June 9

My right glutes and thigh are locked like cement. I wander off on a mental tangent and count the number of arabesque lunges I have on my right leg in the course of this dance—49. Multiply that by running the dance five times a week times six weeks…I reach for my pinky ball.

Lately, as my body is starting to show signs of fatigue, I’m drawn to a somatic approach to warming up, like Feldenkrais lessons, in which underused physical pathways are gently reawakened, allowing more dominant, overworked muscles to chill out. This brings the body back into harmonious integration. This is a fancy way of saying that choreography is lopsided, my right butt is tired and Feldenkrais helps.

June 10

Heidi’s back, for my last rehearsal before tech. She reminds me of words we use as a centering technique to prepare for her installation piece ON DISPLAY (“I am right here”), and also to breathe. I’m a human going through this journey. We talk about how the audience doesn’t want to be told how or what to feel by the performer. My focus has to be so big and so subtle, all at the same time.

Before we leave, she says, “Whatever happens on Sunday is icing on the cake. You took this challenge head-on. You did it.”

June 11, 10 am: Tech

Jillian and I each have one hour, and only one hour, to navigate our new environment. The red steel stage is visually arresting. However, it is raised and does not have wings. Instead it has a ramp to one doorway portal in the upstage-right corner. We quickly repattern our entrances but have no time to drill them. Lush tropical plants line the downstage where footlights might otherwise be. The artist who designed this gorgeous stage-cum-sculpture, Rashid Johnson, is here today, and I’m giddy when I introduce myself. His body of work meets the current political and cultural moment head-on through an aesthetic that resonates with me. We’re also the same age. I’m pumped that our artistic paths are intersecting in this way. He graciously thanks us for “activating the space.”

As always, there’s nothing to do but do it. I start a light run. The floor is slippery with street dust. I adjust. I follow the grid lines in the paneled floor construction to ground the spatial geometry. When I execute my first high release, I see the tops of the buildings and the sky above. It’s righteous.

Around the same time as the stillness article, I remember Joan Acocella writing in another New Yorker review, of New York City Ballet, that Alexandra Ansanelli had danced as if it were her last night on earth. This image is ever present in my mind, and the urgency it connotes fuels every performance I give, even more so now.

While I’m dancing, the artist’s assistants use buzz saws to carve Basquiat-like graffiti into the back and sides of the stage. Buzz saws with sparks flying from them. Buzz saws that aren’t silent. It’s a serendipitous homage to Twyla Tharp’s original Deuce Coupe (1973) when United Graffiti Artists made a graffiti mural onstage while the dancers performed.

A passerby places a portable black speaker on a bistro table 20 feet from the stage and proceeds to blast his own music over my buzz-sawed silence. The first song of his 20-minute set is “New York, New York,” sung by Frank Sinatra.

“If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere.”

June 11, 9 pm

Twenty minutes after lights-out for my 6-year-old, he calls me into his room.

“Is it possible to stay alive forever?” he asks quietly.

I take a very deep breath. I’m not prepared for this.

“No,” I say as factually and as gently as possible.

He begins to whimper softly.

“I don’t want to die. I don’t want you to die. I don’t want Dada to die.”

June 12

Technically it’s a day off, but then that would render my performance the equivalent of a Monday rehearsal, which isn’t what I want. I book myself an hour at Ballet Academy East for a light run.

I paint my toenails the same shade of red as the stage, even though my feet will be socked and shoed. It’s my version of a Karinska treasure “for the soul” secretly sewn into my costume.

June 13. This is it.

I remind my little boy that I’ll certainly see him while I’m dancing, but I won’t be able to react physically with a smile or a wave.

“Why not?”

“I’m not allowed, but I’ll give you a gigantic hug when we’re reunited after.”

He is pleased by this.

“You know, I’m not dancing to any music.”

“Is that hard?”

“Yep.”

“I thought it would be easier.”

“In some ways, but not all. There will be a lot going on…” (I avoid the word “distractions”) “…and I have to concentrate.”

Riding the subway down to Astor Place, I flash back to the last performance of the trio of Unfinished, in December 2019. Jerron had told us the week before that this was to be his last show with Heidi Latsky Dance. Jillian had just told us that she was pregnant. It wasn’t the end, but I felt like the last “man” standing. It was at that moment, right before entering the stage, that I had the first thought of doing the whole dance alone.

After two quiet hours with Jillian in a warm-up studio at Playwrights Downtown, we share a giant hug. I walk alone to Red Stage across the wide lanes of Lafayette Street. It takes forever and not long enough. Time is taffy.

On the ramp behind the stage, I pull on my kneepads and triple-knot my sneaker laces. I slide in my AirPods to noodle around for one last round of “Dance IX,” from Philip Glass’ score from Tharp’s In the Upper Room, which is always the last thing I listened to before going on for the Unfinished trio. Heidi comes back to offer well wishes. I crumple my track jacket on top of my water bottle as I glance at the giant clockface on the building next to the stage. 10:59 am.

Go.

I enter in silence through the upstage portal, taking in the vista through my peripheral vision while walking to my starting place amidst the fronds of a palm tree. My kid, my family, my friends, strangers, pigeons, the Astor Place cube. Heidi tells me later that she burst into tears. It’s overcast, so I don’t have to squint. I can see everything. My brain is full, the internal dialogue unceasing. I can feel the audience come with me. People lean forward on their chairs. The buzz-saw Sinatra is replaced by the rumble of the 6 train underground, and by the migratory birds above who sing songs of their own.

Eventually the mental chatter melts into something wordless.

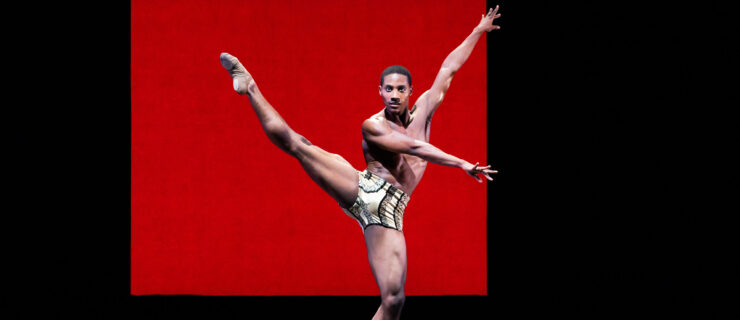

The author in performance

Jerron Herman, Courtesy Fages

Finally, and before I know it, I reach the final section, the solo created for Jerron. Words coalesce. It is a short walking pattern repeated to kaleidoscopic, faceted effect: step, step, rond de jambe to the front that pivots to different corners, with four sets of simple arm gestures. The pattern is anchored by the center-center mark. The rhythm of the footfalls is a gentle but deliberate 1, 2, 3-and…

For the first set, my arms are down loosely by my sides. I feel the weight of my cranium. This is my space. I am neither early nor late. I am right on time. The changes in direction seem to question where I’m going, but I’m not lost.

For the second set, as my feet trace their pattern, my left hand traces my head, making contact with my neck and chest during its journey back down to my side.

For the third set, I lightly tap my right shoulder with my left middle finger, a springboard for an arcing port de bras of my left arm over my head that carves open to shoulder height. My sternum is open, available. I am right here.

For the fourth and final set, my left arm is extended at shoulder height in front of me, scapula stabilized, arm externally rotated. Palm to the side, fingers extended, directed without being locked, with a wisp of a breeze between each. My plumb line is clear, unwavering. At every corner, with every pivot, I reach.

I pivot the final time, center stage, from upstage to downstage, when I interrupt the exhale of the landing by a hair’s breadth of a beat, stopping on the edge of the inhale, in stillness that is motionless yet dynamic, for three voluminous breaths, reaching out in front of me while grounded solidly on two feet.

That I’ve been trusted with this dance is an enormous gift. It came with a lot of pressure, but I’ve never felt so free.

For what do I reach in this final moment?

For you.