Richard Alston Dance Company Gives Its Final Bow, But the Choreographer Is Far From Finished

When the Richard Alston Dance Company performs at London’s Sadler’s Wells this March, it will be the swan song for a company that has been at the forefront of British dance for 25 years, with a choreographer who has been making dance for half a century.

Sir Richard Alston, 71, is the most prominent of Britain’s first wave of contemporary choreographers. News of the company’s closure caused consternation among dance lovers. Alastair Macaulay, former chief dance critic of The New York Times, said it was “unequivocally the grimmest news for British dance this century.”

The decision to close the company came as a result of funding complications. Alston’s financial support from Arts Council England was tied in with that of contemporary dance center The Place, where he is based. When ACE wanted to divert some of Alston’s funding to new choreographers, rather than appeal the decision Alston agreed to fall on his sword in order not to jeopardize the organization’s overall bid.

Soon after the closure was announced, Alston was awarded a knighthood for services to dance, in recognition of a distinguished career that can be traced back to his first ballroom dance classes at his boarding school at the age of 10. Alston joined the inaugural class at the London Contemporary Dance School, founded by former Martha Graham dancer Robert Cohan in 1966, and later studied in New York City with Merce Cunningham. He set up independent dance company Strider before becoming artistic director at Rambert Dance Company from 1986 to 1992 and then founding his own company in 1994.

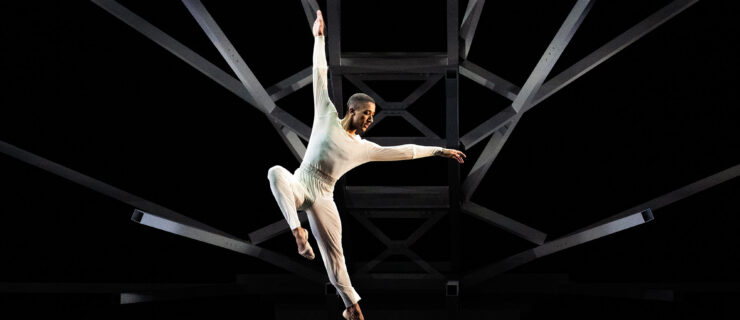

These days Alston is known for contemporary dance full of lilting curves, fleet footwork, weightless jumps and lyrical flow; dances of grace and innate musicality. His final work for his company is called Shine On, a title that gives a sense of Alston’s forward-looking nature. “I’m determined to do what I possibly can to not only shine on as a choreographer, but also for the dancers to shine on,” he says.

The mood on this ultimate tour is celebratory, says Alston. “I have to say I’m having the most amazing time. The performances have been quite extraordinary: The audiences have stood and screamed and queued up to talk to me and there’s been such support.”

To preserve the company’s legacy, its archive of video recordings is being digitized and will be held at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Then, after the closing shows, Alston will take the nerve-racking leap into life as a freelance choreographer. With a strong following in the U.S. as well as the UK (the company gave four farewell performances at Montclair State University in February), he already has an American commission lined up for New York Theatre Ballet.

Alston is saddened by the situation he finds himself in, but also optimistic. “I have been funded by the Arts Council for 25 years, so I can’t grumble because they really have given me room to grow.” There’s no reason that growth need stop. “I’ve done my own self-encouraging research,” he says. “You know Balanchine did Jewels when he was in his 60s? Petipa had hardly started probably!”

Petipa’s most famous ballets, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, were, in fact, all created when the choreographer was in his 70s. All signs indicate that this is far from the end for Sir Richard.