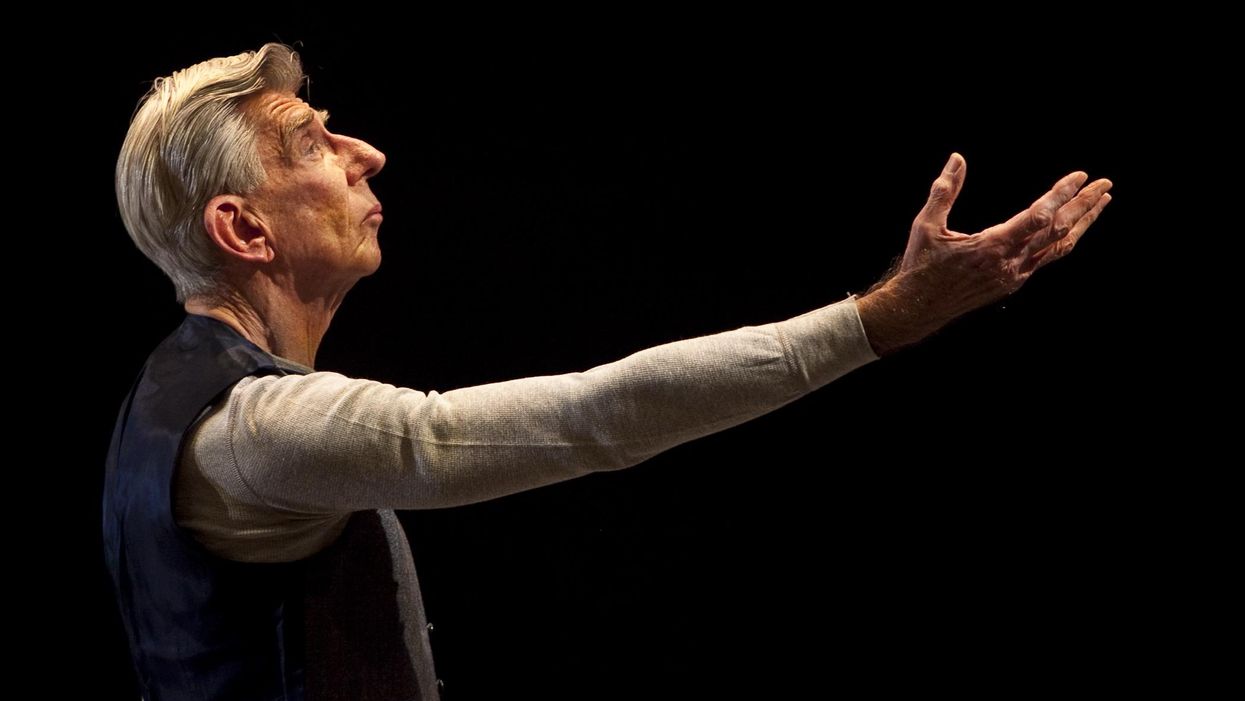

Dancer Thomas F. Dwyer, Who Joined Dance Exchange in His 50s, Dies at 87

Dance Exchange company member, cast member, collaborator and dance partner Thomas Dwyer died on October 8 at age 87.

Dwyer’s influence helped shape the organization that Dance Exchange is today. He was an inimitable force onstage, with a presence that could not be overlooked, and a gentle, humble, witty soul with an infectious smile.

A natural storyteller, he was devoted to the importance of communication. He came to Dance Exchange in his 50s, after he had retired from a lengthy career with the U.S. Department of State, where he had spent time overseas working in telecommunications. Prior to that he was in the Navy for four years as a radioman, and then he worked as an X-ray technician, during which time he met his wife, Doris.

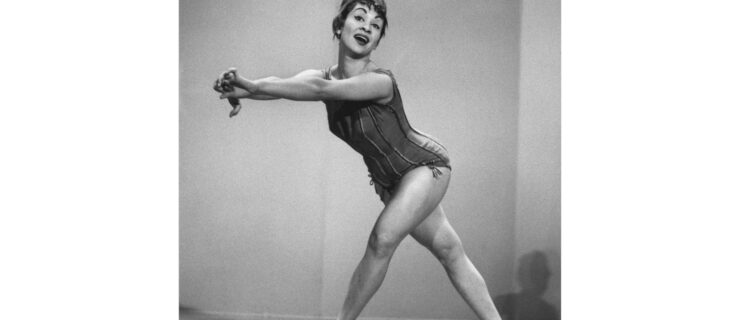

He eventually found his way to Dance Exchange because, at the time, his brother Seymour, also a retiree from the State Department, had been dancing with Liz Lerman’s Dancers of the Third Age, a group with the Dance Exchange composed of older adults who performed in schools, nursing homes, community centers and in concert work. In 1988, Lerman invited Dwyer to join Dance Exchange’s touring company as one of five full-time dancers.

With Dance Exchange, Dwyer performed for more than 30 years in countless pieces, originating many roles in the company’s signature works. This includes works choreographed by Lerman (The Good Jew?, Docudance, Small Dances About Big Ideas, The Music Hall’s Shipyard Project, Hallelujah, Journey, Ferocious Beauty: Genome and The Matter of Origins, among others); as well as those choreographed by current executive artistic director Cassie Meador (Drift, Language From the Land, New Hampshire Ave: This Is a Place to… and How To Lose a Mountain, among others); and by other Dance Exchange collaborators, such as Martha Wittman, Peter DiMuro, Michelle Pearson, Elizabeth Johnson Levine, Jeffrey Gunshol and Celeste Miller, to name a few.

“In all the works I had the opportunity to perform and create with Thomas, he had an unwavering commitment to the process and to the community that grew from each work,” says Meador. “He kept us all nourished through our dancemaking with his incredible baking, his insightful reflections and words of encouragement, and through the thousands of letters and cards he sent to many of us he danced with over the years. Thomas was a tender force, a remarkable teacher and coach, and a loyal friend.”

In her book Hiking the Horizontal, Lerman wrote, “We have a lot of nicknames for Thomas Dwyer. Most people might not find them flattering, but I think he does. He is old-school. His military background, the poverty of his youth, his mother’s love, his coming to dance later in life all add up to a completely unique individual and partner. If I want young dancers to come to see the meaning and reasoning and persistence it takes to remain a movement artist, all I have to do is bring them into an extended relationship with Thomas. You learn a lot, and if you devote yourself to going to this kind of school, the return is extraordinary and powerful. He brings a level of loyalty, commitment, devotion and plain hard work that sets a bar beyond the capacity of those of us living in modern times. We just try to keep up and look for the wry smile that speaks to our success. And meanwhile, audiences are treated to a one-of-a-kind image: an old man dancing with fury, athleticism and tenderness.”

On his bravery, boldness and willingness to take a new direction in his life as an older adult, Lerman recently shared: “Since losing Thomas I have been in deep reflection about all that he was and all that he contributed. He could have taken many other paths in his later life; paths that his peers would recognize and find familiar. Instead, he devoted himself fully to making an embodied case for the beauty of human interaction and the necessity of loyalty as a means of keeping people of difference together with purpose.” —Emily Theys