Is the US Government Cracking Down on Artists' Visas?

In late March, The Joyce Theater’s annual gala performance included a last-minute substitution: Blueprint, by choreographer Pam Tanowitz. The trio took the place of Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Faun, after two Paris Opéra Ballet dancers were unable to secure visas to appear onstage in the U.S.

“It was a shock,” says Linda Shelton, executive director at The Joyce Theater. “In all 25 of my years here, I think we’d only been turned down once before. That was ages ago and we already had a feeling that dancer wouldn’t be approved anyway, because of an issue with their passport. This was just a big, big surprise.”

Less than a month later, news broke that visa petitions for Bolshoi Ballet stars Olga Smirnova and Jacopo Tissi to perform at the Youth America Grand Prix gala had also been denied. In February 2017, Minneapolis presenter Northrop was forced to cancel a performance by South Korea’s Bereishit Dance Company, which was to kick off its second North American tour.

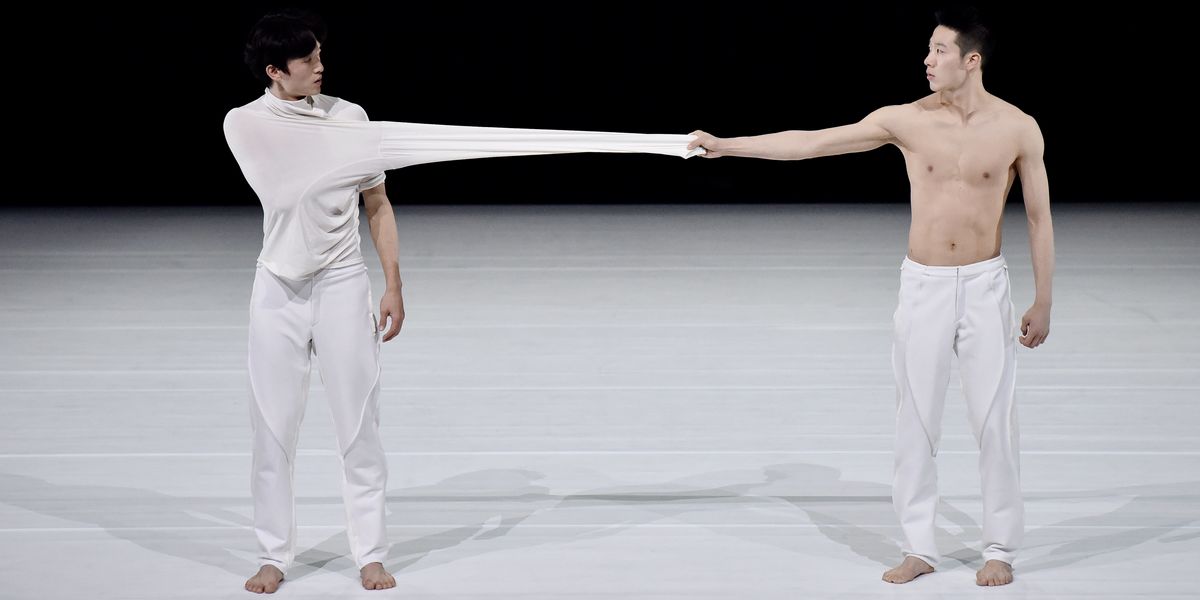

Ballet Nacional de Cuba was forced to withdraw from a performance with the Los Angeles Philharmonic this month due to visa issues. Photo by Quinn Wharton.

Ballet Nacional de Cuba was forced to withdraw from a performance with the Los Angeles Philharmonic this month due to visa issues. Photo by Quinn Wharton.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services is the division of the Department of Homeland Security that decides whether or not to issue a petition approval notice, which is used by the State Department to issue visas to performers from abroad.

Is the department cracking down on cultural exchange and, if so, is it yet another example of the Trump administration’s fixation on foreign nationals in the U.S.?

Not exactly, says Brandon Gryde, director of government affairs for both Dance/USA and Opera America. “It’s certainly not a direct attack on the cultural community,” he says. “We just get caught up in an overburdening of USCIS and in the increase of petitions, I think.”

The two most common types of visas requested on behalf of touring dancers and companies require petitions that include extensive documentation, such as press clippings and marketing materials featuring the artist, support letters, plus an in-person interview at a consulate or embassy prior to entering the U.S.

The first, O-1B (or simply “O-1”), is for one individual “of extraordinary ability in the arts” seeking an opportunity to work in the U.S. The second, P-1B (“P-1”), is for foreign-based groups of two or more artists entering the country solely to perform. Both of these can be requested for a short period of time—a guesting gig or brief tour—or for a longer span, such as a 12-month contract with an American dance company. A third type of visa, known as P-3, may also be requested for culturally unique artists.

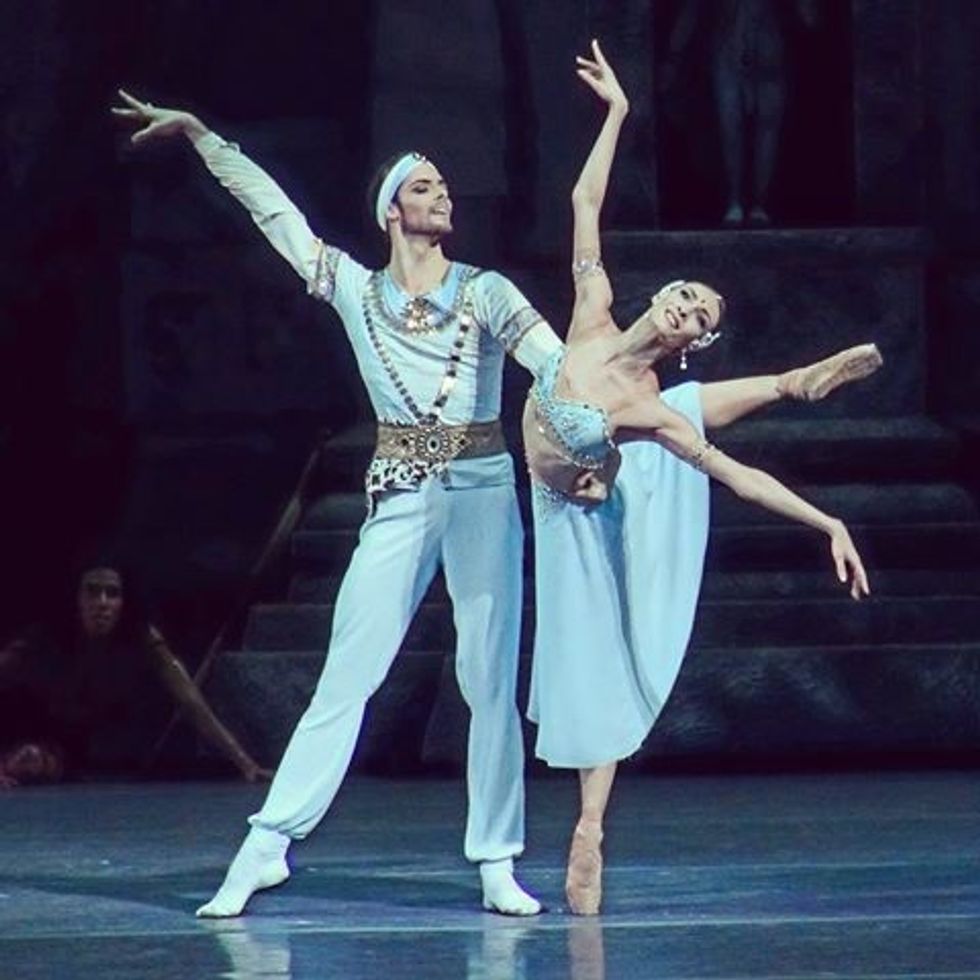

Olga Smirnova and Jacopo Tissi’s visa petitions to perform at Youth America Grand Prix were denied earlier this year. Photo via Pictat

A time-consuming affair, assembling a petition is the responsibility of the U.S.-based employers, agents, managers, sponsors, presenters or organizers that are hosting the artists. Most experts today recommend starting the process at least six months early.

Three months into his presidency, Trump directed federal agencies to implement a “Buy American, Hire American” strategy, says Los Angeles–based immigration attorney Rachel Wool. “This included proposing new rules and guidance for preventing fraud,” she explains. “The bar has risen for initial O-1 applications as well as renewals.”

USCIS makes no distinction between petition requirements for dancers and those filed in more mainstream art forms like music or theater, which, generally speaking, may find it easier to garner press coverage. Precedent doesn’t necessarily make much of a difference, either; Bereishit’s performances at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival in 2016 obviously didn’t grease the wheels around its return to the U.S. the following season.

If an organization gets nervous about the application taking too long, they might opt to pay a $1,225 fee for “premium processing,” theoretically moving it into the fast lane. “As more people get worried about the turnaround time,” Gryde explains, “more people pay for premium processing, which in turn slows down traditional processing time.”

Add to that gridlock the fact that just two USCIS Service Centers process O- and P-type applications—one in California and the other in Vermont—and a nearly 7 percent increase in the number of O-1 visas issued from 2016 to 2017.

Northrop Dance Series’ artistic director Christine Tschida estimates the total cost of each petition to be at least $5,000, not including additional legal consultation or all the staff time involved.

“The whole system is a kind of trap for the unwary,” says Geoffrey Smith, former board chair at The Washington Ballet and a lawyer who has worked on visa petitions for ballet dancers and companies for four decades. “I’m a lawyer who does this for a living, and I’ve still made a lot of mistakes. The government isn’t going to go out of its way to let you know that you’ve made a mistake or, for that matter, tell you how to fix it. One of the problems that we have with both the O and the P visas is that the forms you file for those are the same forms you file for a professional tennis or baseball player. USCIS tries to make one size fit all, which generates ambiguity. I might know that you should simply leave some answers blank, because it’s completely inapplicable to dancers, but that takes experience.”

Jon Ole Olstad says international dancers can end up paying thousands of dollars in legal fees to navigate the visa system. Photo by Erika Hebbert Larsen, courtesy Olstad

Jon Ole Olstad says international dancers can end up paying thousands of dollars in legal fees to navigate the visa system. Photo by Erika Hebbert Larsen, courtesy Olstad

Jon Ole Olstad, 30, is a Norwegian citizen who’s danced in the U.S. on an O-1 visa for three years. He made the decision to move to Brooklyn after leaving Nederlands Dans Theater and a brief stint in Rome with Esklan Dance Company. “There’s a lot more opportunity here,” he says. “More people, more dancers, more companies, more diverse institutions. You meet people from different cultures and that influences your work. That’s certainly been inspiring to me.”

It hasn’t been cheap, however. Olstad says dancers in his shoes pay anywhere from $2,000 to $6,000 for legal counsel, not including premium processing. “It costs about $350 just to collect and print all the materials you have to submit, which people don’t often think about.”

There is a solution on the table which, should it be signed into federal law, would significantly streamline this process: the Arts Require Timely Service Act. It’s promoted by the Performing Arts Visa Working Group, which includes Dance/USA. “What the ARTS Act says is that, if USCIS does not adjudicate a petition for a nonprofit, arts-related organization within 14 days, then it would receive premium processing automatically,” says Gryde. “That would be huge.”

It isn’t just the waiting game that’s frustrating. Some say that, in the current system, the cards are stacked against the brief window of time professional dancers have to pursue their careers. For example, for P-1 petitions, one thing you have to prove is that 75 percent of the company has been working together for at least one year.

“It has always been difficult—much more difficult than it should be,” says Tschida. “More byzantine and so much more expensive than it should be. And it has only gotten worse…but it’s tremendously important that we share the work of other cultures, that we welcome other voices. It enriches the work of our own American artists.”