Vladimir Djouloukhadze, One of Ballet’s Foremost Teachers, Celebrates 50 Years in Ballet

When Vladimir Djouloukhadze met Vakhtang Chabukiani (one of the first men to inject a sense of Georgian folk-dance tradition into 1930s Russian ballet), Djouloukhadze’s life changed. His ballet career would be shaped by the bold and uninhibited movement power that Chabukiani, his teacher, made so globally famous when he staged ballets like La Bayadère. When ballet is combined with character folk dance accurately and without any mocking, the delicacies and manners of the royal courts are married with a more wild, personal spirit that is invited to shine through various social folk-dances.

Djouloukhadze came to the U.S. after dancing for the Georgian National Ballet and other companies, and launched what has become one of the most successful teaching careers combining ballet and character techniques. His students have gone on to become principal dancers and soloists of the major ballet companies—to name a few: Matthew Golding, Rasta Thomas, Melissa Hough, Rory Hohenstein, Brooklyn Mack, Brian Maloney and me!

He was my teacher at the Kirov Academy in Washington, DC, and I remember him working patiently on my turns, jumps, arms and back, day in and day out. When it came to épaulement, how to hold the body with confidence, and how to understand different types of impact the body can have on an audience or partner, he didn’t hold back. This year, he celebrates 50 years in ballet, which will be commemorated with a new Vladimir Djouloukhadze Emerging Artist Scholarship Fund at the Kirov Academy.

What is the most common correction you find yourself giving year after year?

The feet—their significance, shape and strength. The feet are the basis, the guarantee of all types of jumps, turns, etc. Correct feet training prevents injury. I always tell my students, “Your feet are your business card.”

Another important point is the arms. Professional teachers agree that it is very difficult to teach the positions and movements of the arms and hands. Of course, you can’t properly move your arms without the back and shoulder blades.

Which are your favorite tips to give to emerging dancers?

I advise them to exercise discipline. And I don’t mean to come in class on time or any of this sort. The key of any learning is repetition, and discipline is a key to the consistency. The student should be able to clearly repeat what was said in class, memorize all the comments, avoid mistakes and eliminate bad habits.

And, undoubtedly, I advise them not to give up—never, whatever happens. In the process of training, something may not work out well. It does not mean that you have to fold your hands and get upset. You just tell yourself: “If it doesn’t work out, I’ll do it again. I repeat it again and again, and I’ll achieve the result.” They should see it as a challenge, and not as frustration. I care about that.

Also, they should always ask themselves why they are in class. It will keep reminding them of their love for this art form. Ballet is very difficult, physically and emotionally. Only love for ballet, love for beauty, supports us as dancers or ballet teachers.

How do you manage unmotivated students?

I try to inspire them to think, ask questions and find the answers. I also ask them questions. I make sure that the students really understand, as sometimes they nod their heads, but they do not fully understand. By means of questions and answers, I try to help them analyze, think, and understand the logic, since everything is built logically—coordination, positions, etc.

Today’s generation has technological capabilities where you can find a lot of options, see, and compare. And I’m trying to get them to do it. For example, while learning a variation or pas de deux, they can watch different versions and then explain to me why they like this or that dancer more. Their answers help me understand how developed their sense of beauty is, as well as their understanding of ballet as an art form.

Courtesy Djouloukhadze

What is your favorite music to motivate the dancers in class?

Music emphasizes aesthetics and develops taste. I use music by many great composers in my ballet class. You can find humor among composers, or extraordinary dancing music, such as by the “Waltz King” Johann Strauss. This kind of music just pushes you to dance.

Of course, junior students don’t need any kind of drama or emotional experience in music. They need music with a clear rhythm. At a more advanced level, music helps the students to represent different characters bringing their own individuality into them.

I have many favorite composers. Offenbach gives us fireworks of dance music—polkas, gavottes, mazurkas. It is pure joy and cheerful energy. To express jokes and humor, I turn to the humorous music of Shostakovich or Prokofiev, leaving their dramatic works for stronger emotions. Of course, Tchaikovsky conveys a whole range of emotions. I find passion and power in the music of Beethoven and Rachmaninoff, romance in Chopin, Schubert and Schumann.

But working with great accompanists, I don’t even have to choose the music. Not every musician, even a very good one, can become an accompanist. Good accompanists know the names of the ballet elements and positions. When I explain a particular combination to the students, they listen carefully and immediately understand what I want. They can be called nondancing ballet dancers. I recall with admiration my work with Glenn Sales, a concert pianist. Now my accompanist is Regina Martin, a high-class professional who knows all the nuances.

What are the things that Mr. Chabukiani taught you that you take with you?

His main lesson was to convey all emotions not with words but with plasticity, movement. Emotions should be expressed in every movement of the arms and body, in stage walk and run. Absolutely everything can be explained by arms. They can be read like a book. Switching to Georgian, he would say “jokhebi,” meaning that the arms should not be like sticks.

At that time, he walked with a cane. He used to ask us to hold his cane, get into a pose and do the preparation so emotionally. He’d ask “Got it?” And the most amazing thing is that we successfully repeated it after him.

Chabukiani also did a lot as a choreographer. Recognition was given to his ballet Laurencia. He staged the second version of the ballet in 1979 and chose you for the lead role. How did it feel?

It was a great honor and a great responsibility. Laurencia is a ballet with many character dances. It’s just filled with emotions and passion. The Georgian temperament is very close to Spanish. They even assume that the Basques and Georgians are related peoples. In Laurencia, Georgian and Spanish character have been successfully combined and intertwined.

It is recognized that Chabukiani brought in elements that did not exist before him and which still form the basis of male dance. Traditionally, ballet was dominated by female dancers; the man mainly performed the role of a partner, remaining in the shadow of the ballerina. Vakhtang Chabukiani brought the male dancer forward, and choreographers started creating ballets with dominant male parts. For example, Ivan the Terrible, Spartacus, Medea. Even the parts of the classical repertoire have received a new life. For example, in La Bayadère, the part of Solor, in terms of its importance, has come to the fore with Nikiya and Gamzatti.

Your philosophy of the feet and arms that you described are areas that 100 percent shaped new pathways for me. If I am having a bad day, I just think about how I could use my hands or feet a little differently, and it ends up feeding creativity back into the body and mind.

What happens if you are having a bad day?

I think that the teachers should not demonstrate their bad mood. Instead, they should tune themselves and their students up in a positive way, remove all negative things through conversation, good music and the right ballet combination. On such a day, you do not need to do a very difficult, stressful class, but on the contrary, make an easy, pleasant class to cheer everyone up. You can joke, distract students and yourself from difficult thoughts. Do everything so that this day is not wasted.

How have dancers changed over the years in your career?

The physical level has grown greatly, the technique of performance has grown. Unfortunately, the technique began to hamper the emotional component of ballet, spirituality of art. The main focus switched to a number of pirouettes and the quality of jumps, to a desire to do some tricks at any cost or even come up with new tricks. This has become the mainstream today. I would even say that art has come to be equated with sports. I hope this is temporary. I hope that the high level of technique will be preserved and ballet will return to its main mission—beauty, unity with music, and emotions.

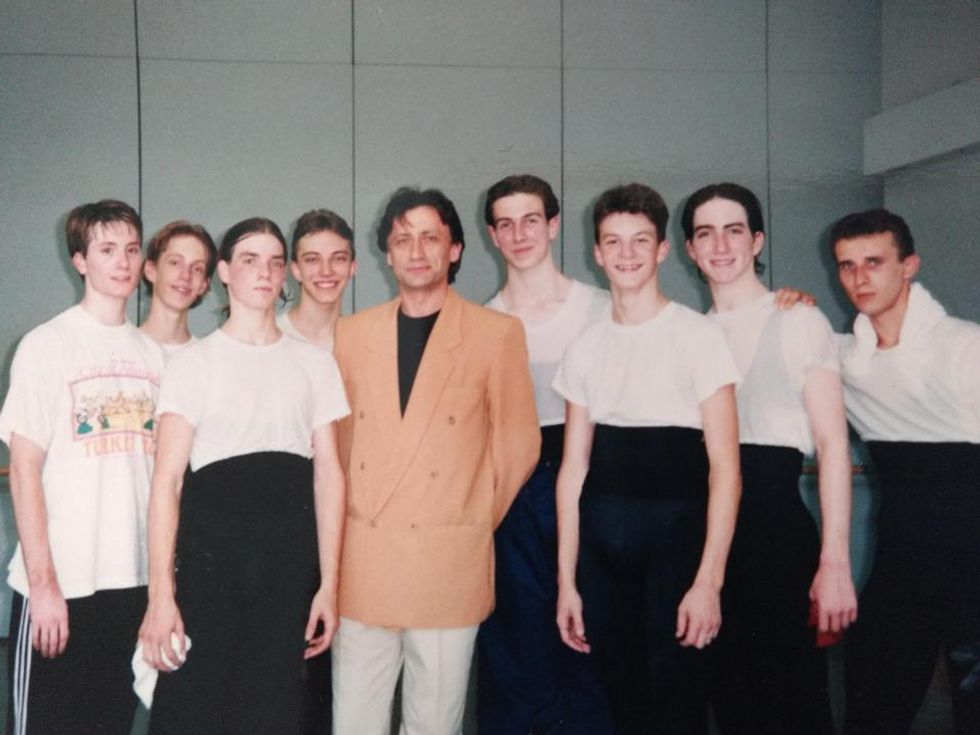

Author Evan McKie (fourth from right) and his classmates with Djouloukhadze at the Kirov Academy of Ballet.

Author Evan McKie (fourth from right) and his classmates with Djouloukhadze at the Kirov Academy of Ballet.

Courtesy McKie

Do you think competitions have advantages for students wishing to become professionals?

I believe they are essential. While preparing for the competition, the dancer approaches the classes more consciously. He or she knows that there is a clear plan for what needs to be done. A sense of responsibility is growing. And it certainly gives them an advantage over other students who can afford not to work that hard on a daily basis and find some excuse to even skip class. Undoubtedly, the progress is faster. The main thing is the process of preparation itself, and not receiving medals, prizes and diplomas.

Do you think character and folk dances should be included in competitions?

Yes, absolutely. It will give the contestants an opportunity to demonstrate all the facets of their talent and will contribute to the complete appreciation of the dancer. Without knowing the basics of character dance—for example, Spanish, Hungarian, Polish—the dancer will not be able to perform every part in Don Quixote or Raymonda or Swan Lake, where various overseas guests are represented at the ball. If a dancer does not know the basics of Spanish dance, how can he dance Basilio in Don Quixote? Every dancer should know how to dance, for example, waltz or mazurka or Hungarian czardas, and every teacher should be able to teach them.

What do you think the dance world is lacking today?

Nowadays, computer technologies are widely used in ballet, allowing to make the design of performances more spectacular. But it seems to me, the traditions that made the performances more fabulous were somewhat lost. Technology should not replace what constitutes the soul of the performance—the emotions, characters and empathy of the audience. I want real people to act in ballet, and not lifeless constructs presented through pantomime. Sincere feelings can be conveyed only by well-trained artists.

I would like to keep the purity of performance and respect for traditions, the preservation of style. Often, excerpts from ballets of different styles are combined together. The same confusion is happening in variations. It seems that people do not understand what they are doing.

Also, I would like more boys to be attracted to ballet. It is necessary to allocate more scholarships and create funds, and tell the stories of the male dancers.

Do you have a mantra?

“Tomorrow I will do even more and better than today.”