Why Crystal Pite Still Feels Like an Outsider in Ballet

A creation for the Paris Opéra Ballet or The Royal Ballet would have pride of place on any choreographer’s resumé. But Crystal Pite is going one better and choreographing works for both companies this season. “Isn’t that crazy?” she exclaims at the Palais Garnier in Paris, still sounding surprised. “I have to pinch myself sometimes when I come into this building.”

Still, Pite has plainly demonstrated in recent years that she belongs at the top of the choreographic ladder. Since creating her own company, Kidd Pivot, in 2002, the Canadian dancemaker has realized her ambitious vision for dance theater in increasingly large-scale productions: the Shakespeare-inspired The Tempest Replica, in 2011, was described by The New Yorker as “a work of astonishing beauty and thoughtfulness.” Since 2013, Pite has been an associate artist at London’s prestigious Sadler’s Wells Theatre, where her most recent works, from Polaris to Betroffenheit, have made her a critical darling.

And while Pite considers herself a contemporary choreographer, the ballet world has paid attention. A former dancer with Ballet British Columbia and Ballett Frankfurt, Pite has made works for Nederlands Dans Theater and the National Ballet of Canada, among others. In September, her Seasons’ Canon made people sit up and take notice in Paris, and The Royal is next for a Pite premiere in March.

“It’s exciting to be able to use that knowledge, that mastery classical dancers have,” Pite says. “How do I use them and still create a piece that looks like something that I would make?”

Given Pite’s background in ballet, it’s not surprising classical companies have come knocking. While there was no pre-professional school in her Canadian hometown, Victoria, British Columbia, she trained at “a very good little ballet school” from the age of 4 to 17.

Her hours were limited, but the school’s focus on the creative process compensated: “My teacher, Maureen Eastick, would make new pieces for us all the time. We had the experience in the early days of being choreographed on.” Her school also entered dance festivals where Pite herself was allowed to develop her creative skills. “We were onstage a lot. I had the opportunity to choreograph on my peers.”

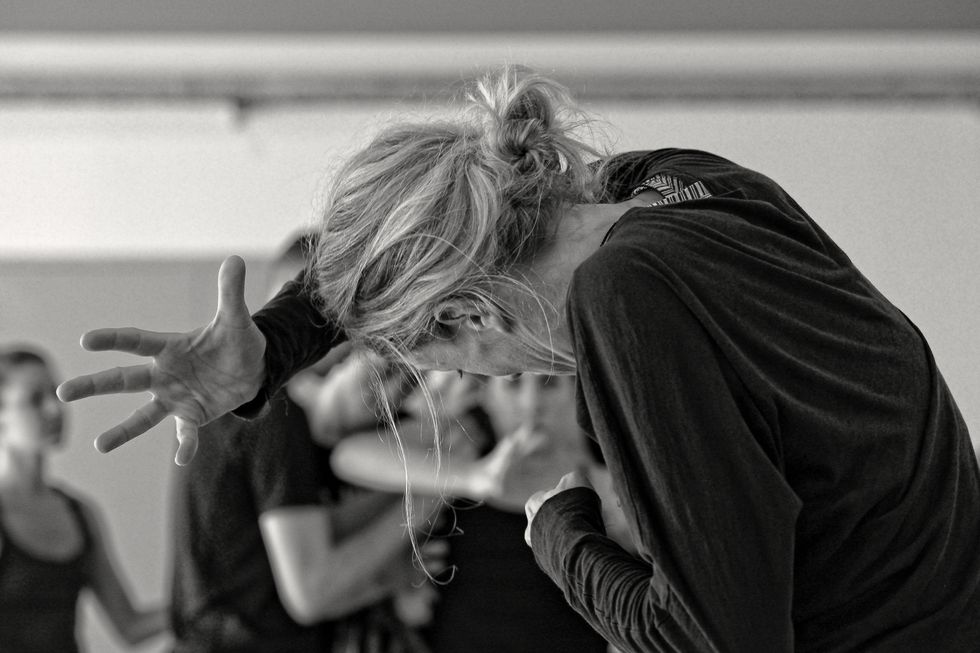

Pite in rehearsal at Ballet BC. Photo by Michael Slobodian, courtesy Ballet BC

After graduating from high school in 1988, she was offered an apprenticeship with Ballet British Columbia in nearby Vancouver. “It turned out that it was the perfect place for me to go,” she reflects. “It was a small company, the focus was on new work and contemporary ballet, and I was able to widen my vision of what was possible in ballet and dance.”

The company’s repertoire included works by Jirí Kylián and William Forsythe, and while her own choreographic career was taking off on the side, Pite opted to challenge herself by joining Forsythe’s Ballett Frankfurt in 1996. Many of today’s top choreographers have come from the company’s ranks, and Pite credits Frankfurt’s collaborative ethos with pushing her as an artist.

“Bill [Forsythe] was attracted to people that were creative to begin with, people that were willing to take risks, and there was this incredible creative spirit at work there.”

By 2001, however, she longed to go home. “I always had the dream to dance in my own work, in my own company, and I wanted to do that in Canada,” she says.

With the support of her long-time partner and designer, Jay Gower Taylor, Pite launched Kidd Pivot. Adequate funding was hard to secure in Canada, but she steadily developed her choreographic voice while dancing in her own works for a decade. “I think those two sides of myself, being a dancer and a choreographer, have always fed each other, and at that point I felt this great synthesis within myself,” she says.

Her retirement from the stage coincided with the birth of her son Niko, in 2011. “I always imagined that my dance career would end when I either got injured or had a baby. Fortunately, it ended up being the latter, but the decline was exponential,” she says with a laugh. “The aging, the child, the challenges of trying to juggle everything! It was a new beginning and an ending all at once.”

Kidd Pivot now works roughly half the year, allowing both Pite and her performers time for side projects. Its bold productions have an experimental, multidisciplinary side to them. Pite’s grounded vocabulary is often blended with text and commissioned music, with Gower Taylor contributing seamlessly modern set designs. 2015’s Betroffenheit, a raw exploration of loss and grief, was a collaboration with actor and playwright Jonathon Young.

“I’m interested in offering an audience a variety of ways to get into a piece,” Pite explains. “Some people can connect in a visceral way to pure movement, and others connect more to language. I like to be able to use anything to get people in the same world as each other.”

Despite the commissions she has lined up, Pite still feels like a visitor in the ballet world, where she is one of the rare high-profile female choreographers.

“Ballet dancers have a very different skill-set and vocabulary. The way they use their spines, their relationship with the floor, to each other in partnering: There is a whole different kind of musculature that kicks in when they connect.”

Pite has adapted, making ballet works that are more dance-centric than her repertoire for Kidd Pivot, and more focused on group work. “I can achieve a physical complexity within an individual body easily with my own dancers, but with dancers I’m just meeting, I’m not going to be able to,” she says. At the Paris Opéra Ballet, she found strength in numbers, with 54 dancers often moving as one—and scenes that paid tribute to their unique lines and technique.

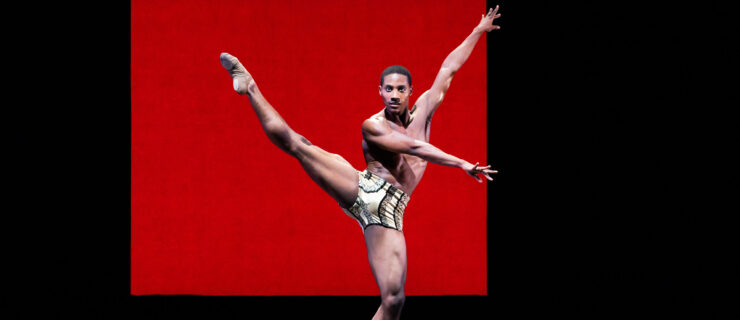

Paris Opéra Ballet in Season’s Canon. Photo by Julien Benhamou, courtesy POB

At The Royal Ballet, Pite will use the first movement of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, “music that is very familiar and beloved,” she says. She plans to “follow its trajectory,” and mine the dancers’ classical training for inspiration.

They will have to adjust to the bold yet rigorous earthiness of her style, however. Pite thrives on the energy that comes from that mix: “When there is tension, something flourishes and becomes alive, complex,” she says. “I want dancing that looks like it’s being discovered in the very moment it’s being danced. I want it to look like it’s reckless, dangerous and also delightful.”