2023 Posthumous Dance Magazine Awards

Founded in 1954, the Dance Magazine Awards have historically only been given to living artists. This year’s new posthumous honors were created to recognize some of the many artists active since 1954 who were not given awards during their lifetimes. The Dance Magazine Awards, which have a theme of education, will be presented at Buttenwieser Hall at The Arnhold Center, 92NY, in New York City on Monday, December 4, 2023.

Syvilla Fort

Later, her name would be associated with the brightest stars of Hollywood, Broadway, and concert dance—Marlon Brando, James Dean, Jane Fonda, Eartha Kitt, Chita Rivera, Geoffrey Holder, Alvin Ailey, Chuck Davis, Yvonne Rainer. Yes, dance educator Syvilla Fort taught them all and more. But her influential teaching career started more modestly while she was still a youth in her native Seattle.

Born in 1917, Fort learned early, as a Black girl eager for ballet, that race and class could be impediments to professional training and a career pathway. Local dance schools refused to admit her, and this bitter lesson inspired her to open her own door to marginalized students in her community. She started to teach at age 9, and her commitment to education and access held steady through a lifetime of accomplishments.

Offered a full scholarship to Seattle’s Cornish School of Allied Arts (now Cornish College of the Arts), Fort became its first Black student and created work in collaboration with avant-garde composer John Cage. She also danced for several years in the legendary company of Katherine Dunham, absorbing the breadth of Dunham’s knowledge of African and Afro-Atlantic culture and movement. After a knee injury cut her performing career short, she served as chief administrator and instructor in the Katherine Dunham School of Dance, later opening her own school and teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University.

When we note the lasting contributions of Black artists to ballet and postmodern dance, fields previously dominated by white bodies, we must also remember Syvilla Fort’s pioneering efforts and her outspoken advocacy for inclusion and social justice in dance.

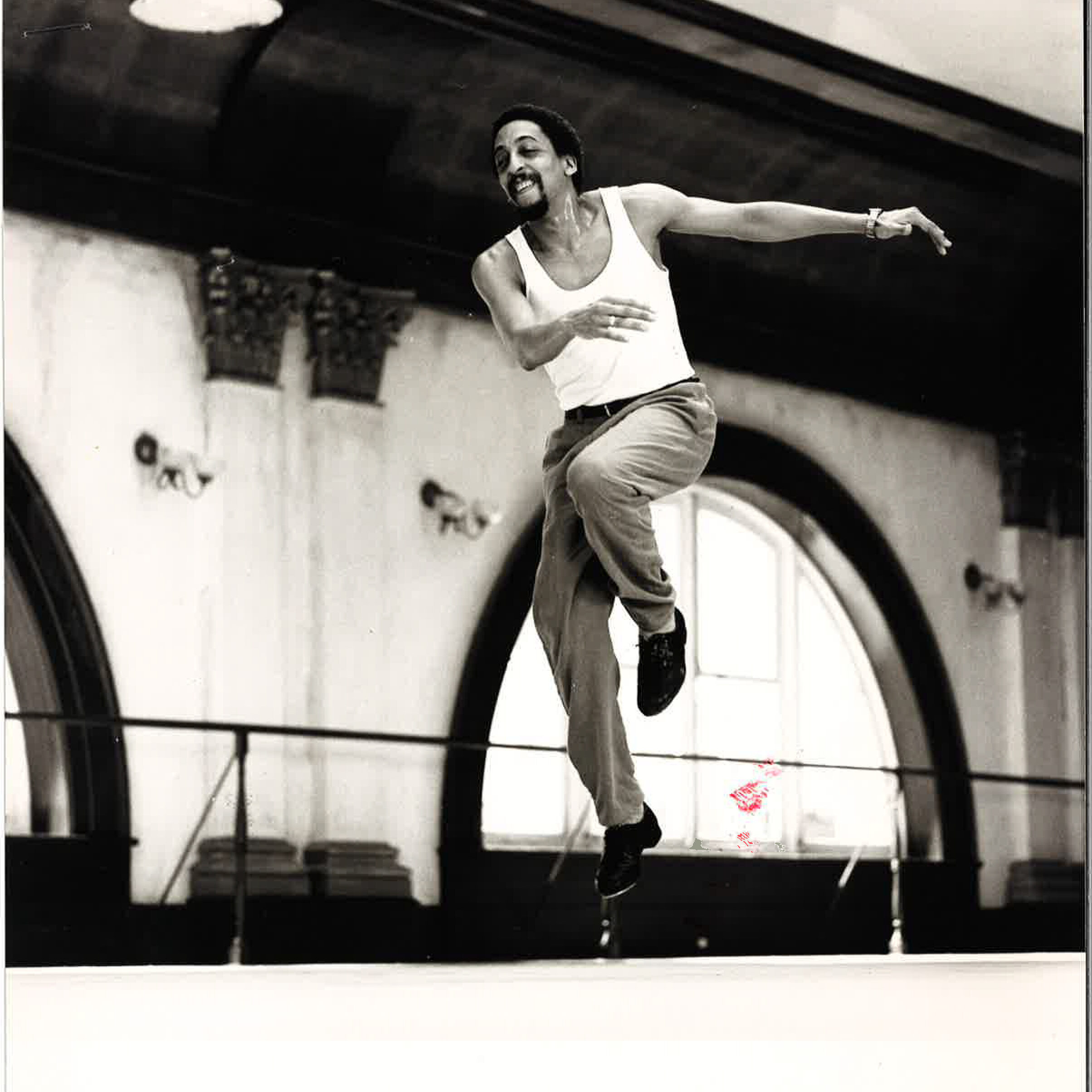

Gregory Hines

A consummate artist and much-loved entertainer, Gregory Hines would have turned 77 this year had he survived the cancer that took him in August 2003.

When artists master more than one skill, they are often called “double threats,” even “triple threats.” With Hines, you could lose count. Since toddlerhood, Hines steadily built his career in the arts, growing to light up the worlds of stage, film, and television as dancer, choreographer, actor, singer, musician, director, and teacher. His star blazed as the near-forgotten art of tap enjoyed its first major revival and newfound popularity. With his creative skill, irrepressible zest, and charisma, Hines served as a bridge between two great eras of tap dance—old-school veterans like Charles “Honi” Coles, Bunny Briggs, and Sandman Sims, and crusading innovators like Savion Glover and Jane Goldberg, followed by today’s superstars, like Ayodele Casel and Dormeshia. Hines was there to catch the torch and pass it on just as he said his friend, the multitalented and world-renowned Sammy Davis Jr., had passed it along to him.

Fans of tap thank Hines also for his advocacy in lobbying the U.S. Congress to create the annual National Tap Dance Day (May 25), which launched in 1989 and has since gone international. And, like one of many recent honors awarded to Ms. Casel, in 2019, Hines received the distinction of becoming the face of a United States Postal Service Forever Stamp.

An ambassador of tap, Hines continues to be cited, year after year, as a mentor, friend, and inspiration to many. By giving tap an elevated place among his many talents, Hines assured not only that historic and contemporary Black rhythm tap would get more exposure but that dance, overall, would reach more hearts across the U.S. and beyond.

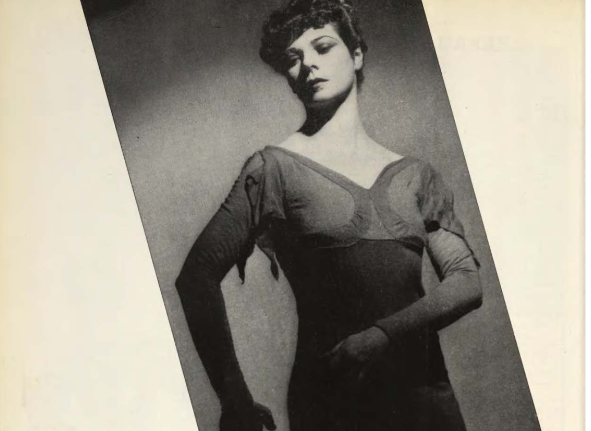

Pearl Primus

A native of Trinidad, Pearl Primus built her long, distinguished career in choreography and education on immersive research into African and African-diasporic cultures. As she wrote in a 1979 statement, dance became her vehicle and language; her freedom and her world; her medicine and strength; her scream and fist; her teacher.

In 1941, discouraged by racism in academia, Primus shifted from biology/premed studies and took up with the artist-activists of New York City’s New Dance Group, becoming its first Black student. The influence of Sierra Leone–born musician and dance artist Asadata Dafora helped this young scholarship recipient define her life’s work. Primus’ later anthropology field studies, choreography, and innovative staging of traditional dances would have significant impact on the world’s appreciation for the dances of Africa and the Caribbean and the experiences of Black people in the American South. Her work reached historic and illustrious concert stages—from her 1943 debut at 92nd Street Y to Carnegie Hall, Broadway, Jacob’s Pillow, and many international venues. Primus earned a doctorate in anthropology from New York University in 1978 and was awarded the National Medal of the Arts in 1991.

An electrifying performer, Primus was also notable for thrilling stagecraft. Rather than approach source cultures and communities in exploitive, extractive ways to merely entertain, Primus opened an intellectual and emotional gateway for audiences, rooting her work in authentic contexts, technical excellence, and political meaning.

Primus was not content to dream up dances in her studio. She sought to move hearts towards compassion and social justice. To develop Hard Time Blues (1945), for example, she labored alongside Southern sharecroppers, gaining direct understanding of their struggles. Some of her most notable works deal forthrightly with racist violence—lynchings (Strange Fruit, 1943) and the bombing of a Black church in Birmingham, Alabama (Michael, Row Your Boat Ashore, 1979). Her profound influence continues in the progressive, community-focused aims and methods of dancemakers today, such as Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, Zollar’s Urban Bush Women lineage of artists, and Orlando Zane Hunter, Jr. and Ricarrdo Valentine of Brother(hood) Dance!

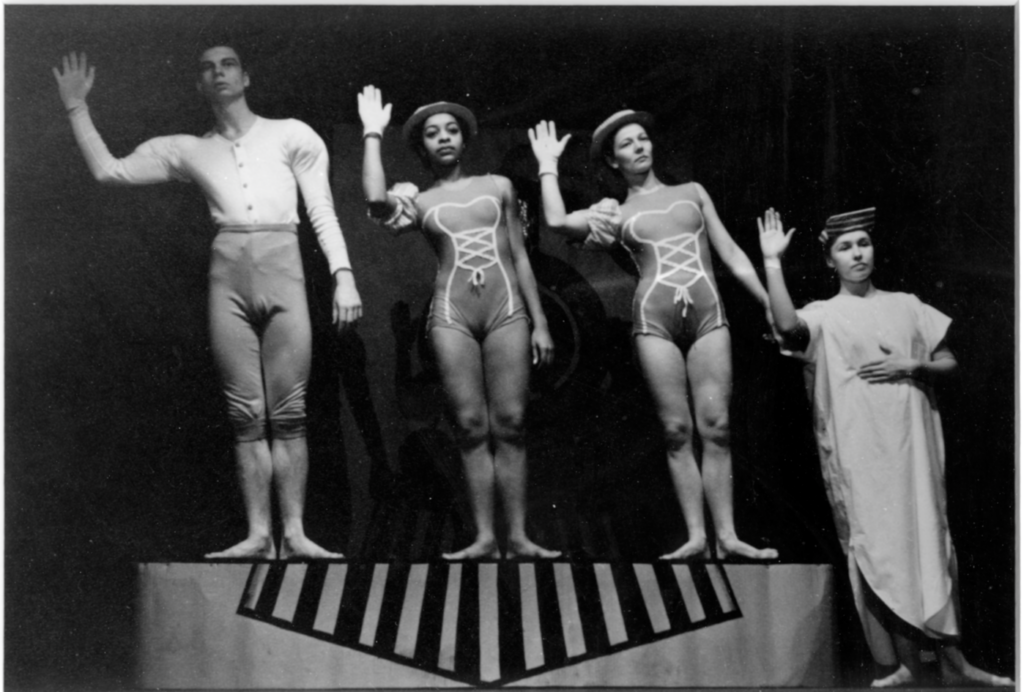

Helen Tamiris

Helen Tamiris lived an exemplary New York story. Daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side—different sources give her birth year as 1902, 1903, or 1905—Helen Becker renamed herself Tamiris, aligning with the ancient warrior queen of a nomadic Persian people.

A brief, unhappy stint in the corps de ballet of the Metropolitan Opera’s ballet troupe followed early training in Isadora Duncan–inspired modern dance at the historic Henry Street Settlement Playhouse. In the 1930s, she discovered her own voice as a choreographer and educator, eventually partnering with Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, and Charles Weidman to found and direct Dance Repertory Theatre, an early example of an artist cooperative in dance. She also launched the School of American Dance and her own first ensemble.

During the Great Depression, concerned about widespread unemployment in her field, Tamiris successfully lobbied the Works Progress Administration, part of FDR’s New Deal initiative, to build an employment program for dance artists, comparable to what the WPA offered the theater industry. The Dance Project ran for four years, with Tamiris as its chief dancemaker. In 1939, the WPA fell victim to growing political polarization, similar to what we face today, as fiscal and social conservatives cut further Congressional funding. In the 1940s, Tamiris moved on to Broadway, finding success making dance for musicals like Annie Get Your Gun and Touch and Go, for which she won a Tony.

Her courage in addressing poverty, discrimination, antisemitism, and war in her works and to train and employ Black dancers likely led her to be less celebrated than other giants of modern dance of her time. But we can consider Helen Tamiris a courageous progenitor of today’s dance artists grappling with similar issues of representation, culture, and conscience.