A Breakthrough for the Limón Company—Bare Legs

There was something very different about the Limón Dance Company last week during their season at The Joyce Theater. It was the costuming: For a long time, women just did not expose bare legs in the modern dance land of long dresses and long tights. But seeing the Limón dancers in Kate Weare’s Night Light (2014)—suddenly they looked more like today.

Night Light

costumer Fritz Masten dressed the dancers in loose tops and bare legs, giving the dancers a whole new look. The choreography transformed the elegant dancers into adventurous, even confrontational beings. With those bare legs, they sliced the space and entangled their partners. The dancers were restless rather than noble, human rather than heroic.

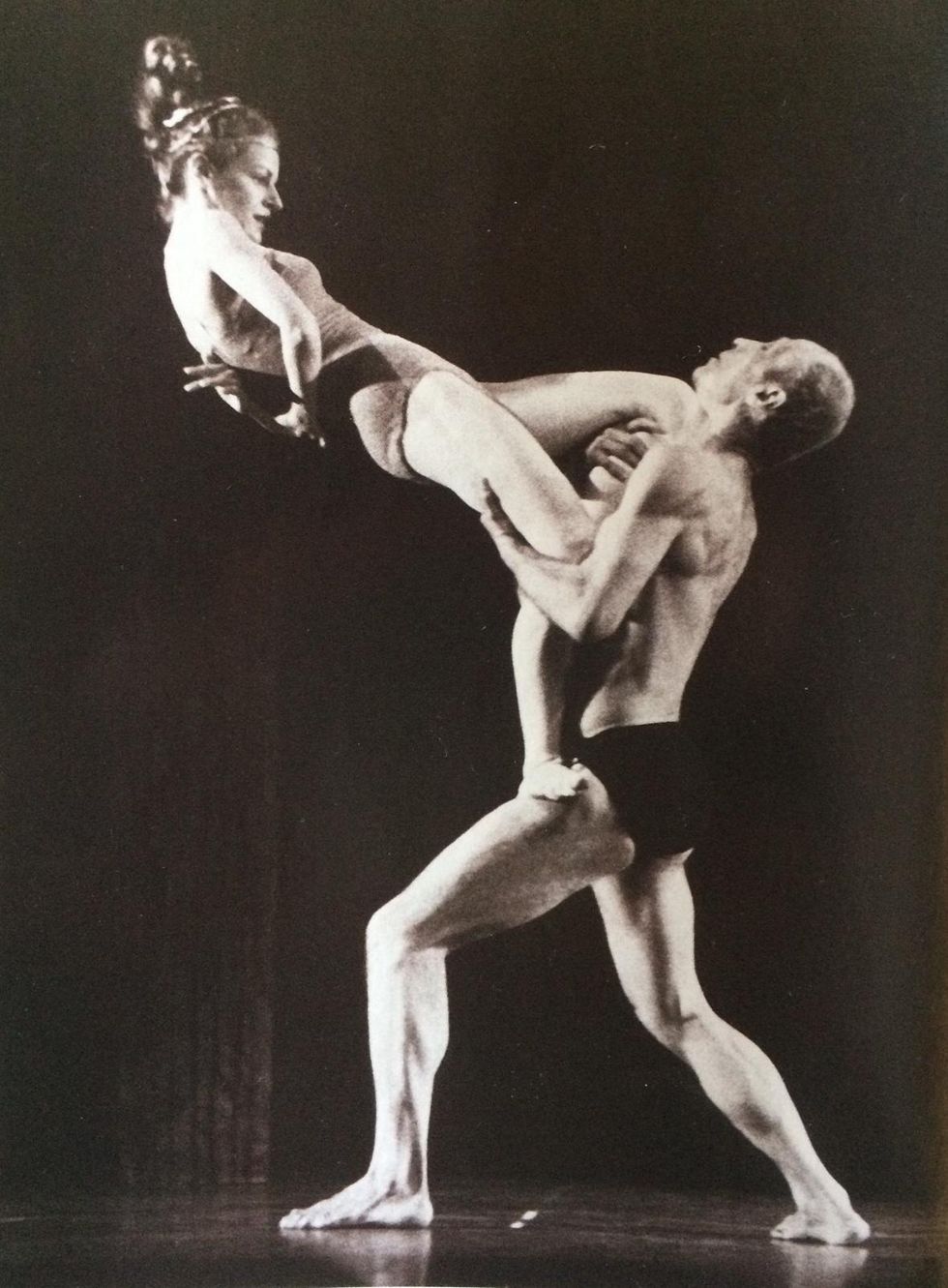

But here’s the funny thing about styles that look new: Sometimes they hark back to the old. Take this photo of Betty Jones, brazenly bare-legged, with Limón in his The Apostate from 1959.

The Apostate (1959) with Betty Jones and José Limón, Photo by Matt Wisocki, Courtesy DM Archives

Of course there were classic Limón pieces at the Joyce too, in which his famous humanity was expressed in large, sweeping movements. But what I rediscovered is that, whether or not you like that aesthetic, his choreographic craft is a lesson in itself. In Concerto Grosso (1945), a trio, the architecture has a keystone in the male dancer, but the patterns are not predictably symmetrical. The clean lines and crystalline counterpoint give a sense of spiritual uplift. There’s a nobleness to the dancers’ stretched and etched lines.

Concerto Grosso with Elise Drew, Jesse Obremski and Kathryn Alter, Photo by Ben Licera

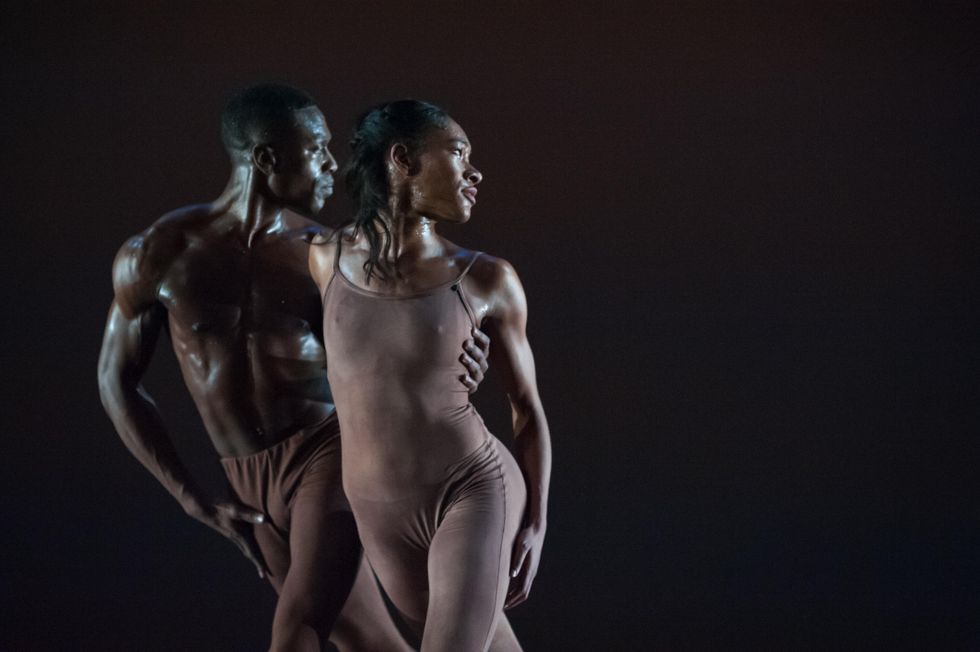

The Exiles

(1950) takes this nobility and makes a story of it. Well…it’s an old story: Adam and Eve and their cycle of attraction, intimacy and shame. There are no airborne lifts like in ballet. The partnering is grounded, with leverage, with effort—and startlingly inventive. Kristen Foote, one of New York’s most magnificent dancers, passes through the changing emotions with honesty and dignity, while her partner, Mark Willis, is unwavering in his strength.

Mark Willis and Kristen Foote in The Exiles, Photo by K. Chang

Back to Kate Weare’s work. Perhaps, under the direction of new artistic director Colin Connor, the definition of humanity in the Limón company is changing. Weare’s angular moves and sharp interactions challenged the dancers to inhabit another mode of expression. In this “Choreography in Focus,” she talks about giving roles to dancers that change them “psychophysically.” But again, perhaps that’s a clue to her ability to renew a kind of rawness that Limón had back in 1959.