From Civil Rights to Bruce Lee: These Are The Influences That Shaped The Birth of Hip Hop

Thirty-five days before I’m born, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is murdered. The Godfather of Soul, scheduled to perform in Boston, Massachusetts, the very next day, is asked to help quell the enormous tension in the air. Meanwhile in California, a struggling Asian American actor and martial artist is developing a style that will influence millions.

It is from this tumultuous time that the culture called “hip hop” will spring forth in the Sedgwick and Cedar Houses in the Bronx five years later, on August 11, 1973.

The culture is born of struggle and oppression, resulting directly from the end of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and the culmination of the Vietnam War. Many Black and Hispanic people in New York City are jobless, living in crime- and drug-ridden neighborhoods. Gangs are prevalent, and poverty is high. As was the case during slavery and Jim Crow, African Americans and their Hispanic brethren look to music and dance to uplift their spirits.

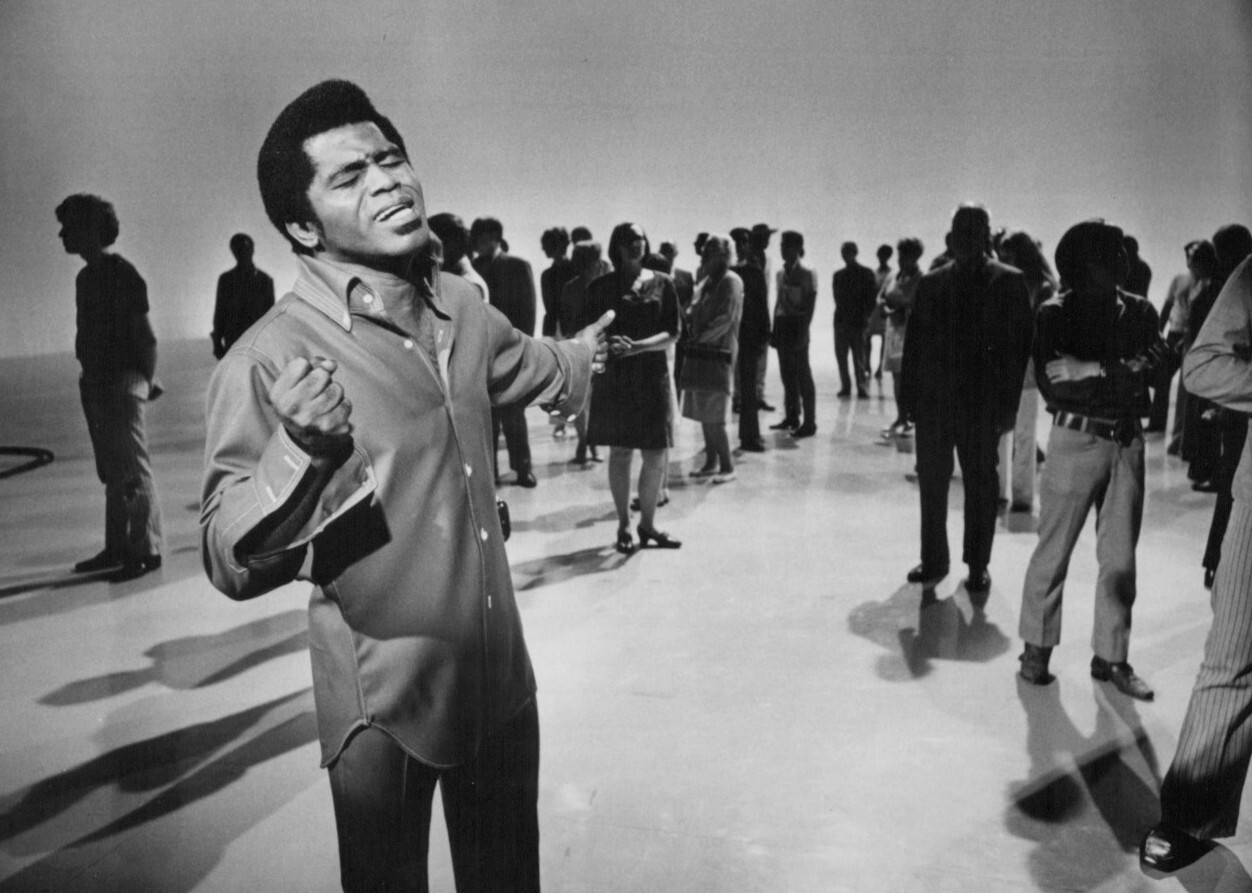

As the Godfather of Soul, James Brown’s music is prominent in that upliftment, and inspires a new style of dance and culture. His emphasis of the drum sound, specifically treating all the instruments like drums, shapes the basis of the sound that will define hip hop: the “break beat,” which is the part of the song that breaks down into just the rhythm section, primarily with percussion. The DJs at the time extend this using a technique coined the “merry-go-round,” in which the drums are manually looped, keeping a continuous rhythm to allow the dancers more time to “go off,” and dance harder. The architect of this is DJ Kool Herc. It is at his parties—starting at the first one on August 11, 1973—that this method is honed, and it becomes the basis for the culture. Kool Herc and his partner Coke La Rock name the dancers “b-boys” and “b-girls,” the “B” emphasizing the break beat, and breaking is born. With James Brown being so influential, he is considered the first b-boy.

During this same year as the birth of hip hop, we experience the death of whom many consider the second b-boy: Bruce Lee. His biggest film, Enter the Dragon, has just been released. He tragically dies before it comes out, but his impact on popular culture is cemented. His fluid fighting style, confidence, swagger, footwork and speed influence the burgeoning breaking movement.

Meanwhile in Brooklyn, a 5-year-old me has just become enamored with a TV show that debuted two years prior. “Soul Train” had invaded American TV screens in 1971, showing live Black music and culture to the masses for the first time. Its impact on the psyches of Black and Hispanic youth cannot be overstated. A young Donald “Campbellock” Campbell shares his dance style, now known as “locking,” on this show, and his manager, Toni Basil, is widely credited for coining the term “street dance.”

Flash forward to ’78. My being a direct beneficiary of the Civil Rights Movement manifests in my getting bussed to a largely white school, where I’m exposed to classic rock: bands like Aerosmith, Queen, Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones. The rapper Keith “Cowboy” Wiggins is said to have invented the term “hip hop” this year, the onomatopoeic phrase mimicking the marching cadence of soldiers. A year later, “Rapper’s Delight” is a smash hit, becoming the first rap record played on commercial radio and selling 2 million copies. But breaking has lost its steam, with dances like the hustle and the freak taking over the dance floors.

Then, groups like the Rock Steady Crew and the Dynamic Rockers reinvigorate the dance, with an evolution of movement not seen in the previous generation: They introduce faster footwork, spins and aerial acrobatics with an even greater competitive zeal. The new decade of the ’80s ushers in an explosion of rap music. More dance styles debut on “Soul Train” with the Electric Boogaloos performing popping and electric boogaloo. I make my own foray into dance in 1982, the same year an article in The Village Voice about Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation marks the first time the name “hip hop” appears in print. The term is used to identify the entire culture of the DJ, emcee, graffiti artist and b-boy. By 1985, the culture explodes globally, led by the dance and the music that inspires it. Overexposure and commercialization leads to breaking being treated as a fad. But a change in the tone and texture of the music brings about what some refer to as the “Golden Age.”

The proliferation of sampling in ’86 brings a resurgence of the breakbeat. Saturday afternoons are filled with kung fu cinema, and the martial arts of the East permeates the minds of kids in the West, inspiring new movements in the dance once again. Cartoons, toys and TV shows influence dances like the Smurf, the Cabbage Patch, the Steve Martin and the Alf. These steps become mainstays in the New York night life. A new form of the b-boy emerges, and freestyle hip hop is born, remixing breaking with popping and the latest social dances. The dance is popularized in the emerging music-video culture of MTV and BET. My first crew, the J.A.C. dancers, is featured in videos by rap legends KRS-One, Salt-N-Pepa, Whodini, LL Cool J and others. In 1989, with the help and urging of my mentor and big sis Robin Dunn, we start the very first hip-hop freestyle class at a mainstream studio at Broadway Dance Center in New York City. The culture comes full circle, and inspires the hearts, minds and bodies of youth around the world.

Emilio Austin Jr. (“Buddha Stretch”) is a b-boy, emcee, graff writer, DJ, choreographer, hip-hop scholar and teacher. He co-founded the crew Elite Force, which grew out of MOPTOP.