Why Is American Flamenco So Undervalued?

Irene Rodriguez’s recent

Dance Magazine interview—which mentions only a few of the many flamenco companies in the U.S. and claims a lack of innovation in American flamenco, and has already drawn criticism in a letter to the editor penned by Ensemble Español—brings to the forefront a deeper problem surrounding flamenco in the United States.

Why are so many flamenco dance companies and dancers in the U.S.—especially those pushing the form forward—overlooked and undervalued? Why do we constantly have to defend our work?

When I toured the U.S. with Flamenco Vivo, my first two tours I wore the iconic red bata de cola. I’d run onstage and hit a pose in the middle of the first piece—and almost without fail, the audience would cheer. I’d hold my pose, chest and chin lifted, castanets drawn and ready. But in my head, I was thinking: Why are they clapping? I’ve done nothing worthy of applause—entering the stage and making a pose is not such a special feat. Presumably, it was the appearance of the red dress and the dramatic change in lighting.

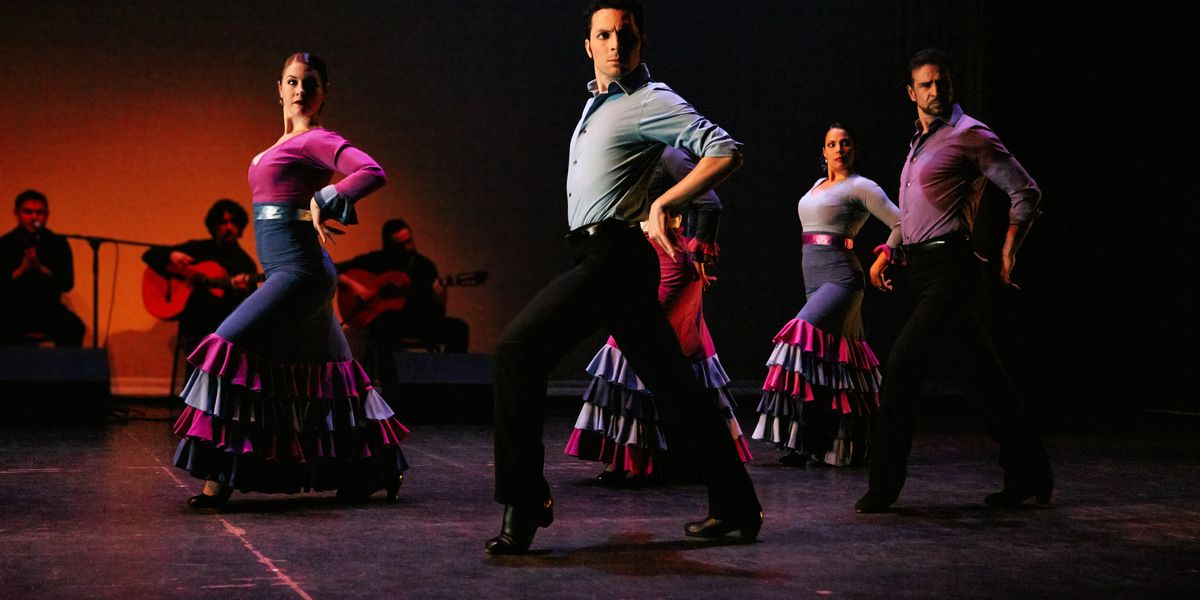

Angelica Escoto, Courtesy Flamenco Vivo Carlota Santana

Why is the audience trained to clap at that moment? I could start with Franco, who used the image of the flamenco dancer to attract tourists to Spain. The woman in the red dress is even an emoji. Hollywood’s portrayals of flamenco dance have not always helped either—such as casting the revolutionary flamenco dancer Carmen Amaya in stereotyped “gypsy” roles.

Pursuing flamenco outside the norms is not so easy. I thought I’d try to present work in the experimental dance circuit where I expected an openness to new ideas. While in NYC, I applied to many performance and residency opportunities, and was rejected from all of them—my favorite rejection being when I was literally stopped mid-dance phrase at an audition because they could not have me doing footwork on their floor. (I always make it clear in applications that I will be wearing flamenco shoes and doing footwork. Finding space to rehearse and perform percussive dance comes with its own challenges.) Sometimes, flamenco is sidelined because it isn’t fully understood. (One MFA program called and asked me why I wanted an MFA, since I was a flamenco dancer. Only upon including in my answer that I also study contemporary dance and had a foundation in ballet did it seem to make sense to them.)

I am ever-grateful to my experiences dancing with several of companies Rodriguez admires, along with many others not listed. But only as I started to branch out did I realize there are many people breaking boundaries in flamenco in the U.S. in incredible ways that could only be possible in the melting pot that is America. Companies like Clinard Dance, Cristina Hall, Juana de Arco, Zorongo Flamenco Dance Theatre, Al Margen, Nu Flamenco, Pasión y Arte, Nélida Tirado, Fanny Ara, (my own company, ABREPASO) and so many more. (I think listing artists is dangerous, and perpetuates the problem of some people not getting recognized, but I also want to show how many incredible artists push flamenco forward in the U.S.) Rodriguez mostly mentions dancers in NYC and New Mexico, but many cities in the U.S. champion vibrant flamenco scenes with outstanding dancers and musicians, and some, like Pittsburgh and Austin, have burgeoning scenes. Building a flamenco community takes decades of tireless work, and many of us creating today are standing on the shoulders of often unrecognized artists.

Daniel Tang, Courtesy Blumenfeld

As foreigners, we have to prove five times over we know the rules before we can break them. I’m sure plenty of people saw my work and said that’s not flamenco, or that I was appropriating or didn’t know flamenco. And if we refuse to take a Spanish stage name, a mainstream audience often questions the quality of our work. How many times have I been met with the response “so that wasn’t real flamenco?” after someone learns that I am not Spanish? Recently, someone said to me “wow, you’re as good as people I’ve seen in Spain!” While intended as a complement, I found the remark to be an insulting assumption that one’s dancing abilities are limited by nationality or ethnicity. From countless conversations with colleagues, I know these types of reactions are, unfortunately, common.

I want aspiring flamenco dancers to know it’s okay to not wear a red dress and polka dots, to branch out, and to explore one’s own style, story and self through flamenco. And I want audiences to know flamenco is more than passionate and fiery footwork, and to not dismiss performances just because they don’t fit their vision of what flamenco is “supposed to be” or because the artist isn’t Spanish. I want people to understand there is an ever-expanding horizon in flamenco, that flamenco has a specific (and fascinating!) political and cultural history. Yes, there are varying qualities of flamenco performances, but I trust audiences to know when dancers have put in the work behind the scenes. Flamenco can be for anyone willing to put in the time to study it—the technique, structures, history, music—and then deepen that knowledge with their own interpretation.

Many flamenco dancers and companies in this country are already here and continuing to push forward. We need the audience to meet us there. It’s not a process that will happen overnight. We don’t have a singular national flamenco or Spanish dance company as Rodriguez calls for. And we don’t need it. We have a uniquely American flamenco scene filled with a diverse array of exquisite artists and companies. Olé to flamenco in the U.S.