Looking Back at the Trailblazing Legacy of Arthur Mitchell—And How He’s Still Influencing Ballet Today

“Lydia, every gesture, every move you make has to come from inside, has to have purpose. It has to make sense to you, so it makes sense to the audience.” This was priceless advice to me, especially when performing Jerome Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun, a ballet rich in nuances. “Oh, and by the way,” Arthur Mitchell added, “I’m asking Cicely Tyson to come in and coach you on the acting.” Wow. Talk about a guiding light!

Arthur Mitchell was my mentor. He was the miracle who crossed my path and introduced me to the world of professional ballet. He transformed my universe into sold-out performances, worldwide travels, and even the privilege of being the first Black ballerina featured on the cover of this magazine in 1975.

His unique brand of discipline, work ethic and presentation both onstage and off was drilled into the minds and bodies of his emerging Black ambassadors of ballet: “Hold your head up high, walk into a room with confidence. People will take notice and say, ‘Who is that!?’ ” We applied this same pride to Dance Theatre of Harlem’s performances onstage. The ultimate reward was respect and longevity for the world’s first successful company of Black ballet dancers—and continued excellence in whatever path his dancers chose after the ballet slippers and pointe shoes came off for good.

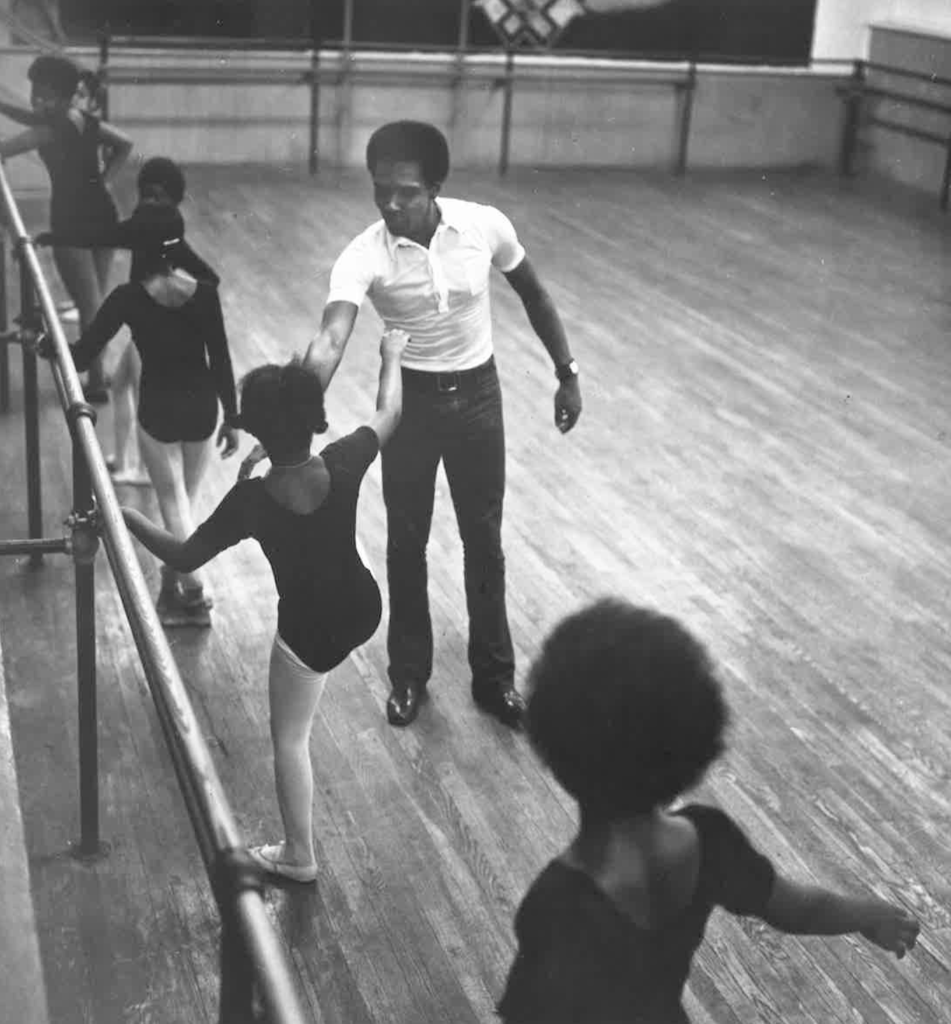

Studying with someone with so much drive and energy accelerated the learning process for all of us. Details that would normally take years to perfect were within grasp much sooner. When Mr. Mitchell entered the dance studio, you were expected to give 100 percent, always. If you weren’t dancing, you were listening and learning on the side, adopting any corrections given as your own. He would admonish, “You can’t learn ballet by osmosis!”

Mr. Mitchell was like a tornado, a controlled whirlwind of determination that brushed obstacles away, protecting the eye of the storm which contained his dancers and the direction he planned for them. No financial hurdles, need for studio space, arguments or rationale against ballet for Blacks could deter him. His intensity could be nearly intolerable at times, but was conceded by all as effective. He was always moving forward. You didn’t want to feel his wrath if he had to repeat something you had already been told.

Arthur Mitchell destroyed the myth that Black people could not or should not pursue careers in ballet. The repertoire was as classic, neoclassical and diverse as his dancers. DTH’s Creole Giselle was performed to rave reviews with the groundbreaking concept of changing the locale from Germany to Louisiana to make it more relevant for his dancers. The company introduced George Balanchine ballets to countless audiences outside of New York City, performed dramatic ballets like A Streetcar Named Desire and Fall River Legend, and dazzled audiences with its fantastic Firebird. Innovative works by Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson and Billy Wilson, renowned choreographers of color, were treasured crowd favorites.

Yet today, after all these years, I am saddened that there are still so few dancers of color in other well-established ballet companies, and I refuse to believe that it’s because they are not good enough. I’ve been privileged time and time again to see excellence up close—and color was not the determining factor.

That’s not to say that Mr. Mitchell’s influence can’t still be felt. There are many former DTH students and company members whose work ethic and discipline continue to reflect his principles, whether as dancers, teachers, choreographers, artistic directors or even doctors, lawyers and college deans. He would be so proud.

I have worked with Ballethnic Dance Company in Atlanta as a coach, teacher and rehearsal director for years. The co-founders, Nena Gilreath and Waverly T. Lucas II, trained directly under Arthur Mitchell, and they continue to instill his brand of excellence in their dancers. I am elated that their company has enjoyed over 31 years of existence and is still going strong. I have the same confidence in Collage Dance Collective in Memphis under the direction of yet another DTH alum, Kevin Thomas. They remind me very much of the young and focused group we once were under Mr. Mitchell.

Another contribution Arthur Mitchell made to the world of ballet was the promotion of flesh-colored tights. These were brought to his attention by Llanchie Stevenson (now Aminah L. Ahmad), one of his founding ballerinas, who insisted on wearing brown tights over her standard pink ones in class and rehearsal. It made perfect sense to him since this matched her overall skin tone. Decades later, dancewear companies are finally offering tights and pointe shoes in several flesh-colored shades, understanding the importance of continuing the lines of the legs through the tips of the toes.

I am blessed to be a member of the 152nd Street Black Ballet Legacy, an organization composed of five ballerinas dedicated to giving voice to those individuals responsible for Dance Theatre of Harlem’s success in its early years. We are determined to preserve the legacy of Arthur Mitchell and other visionaries who contributed to the promotion of dancers of color in ballet. Let us continue to celebrate Arthur Mitchell: the man, the dancer, the trailblazer.

Lydia Abarca Mitchell (no relation to Arthur Mitchell), a former Dance Theatre of Harlem principal and founding company member, is Ballethnic Dance Company’s rehearsal director.