4 Artists of Color Step Into Leadership Roles

Janine N. Beckles, Clifton Brown, Kiyon Ross and Helanius J. Wilkins span generations and geographies. All four have recently transitioned into leadership roles, in dance companies and, for Wilkins, a university theater and dance department. While the differences among these artist-leaders are readily apparent, their experience in the dance community, the wisdom they bring to their new roles and their priorities have distinct parallels. During discussions about leadership and the dance community, several themes emerged, including mental health and wellness, the importance of dancers having a voice, the value of mentorship and being a lifelong learner.

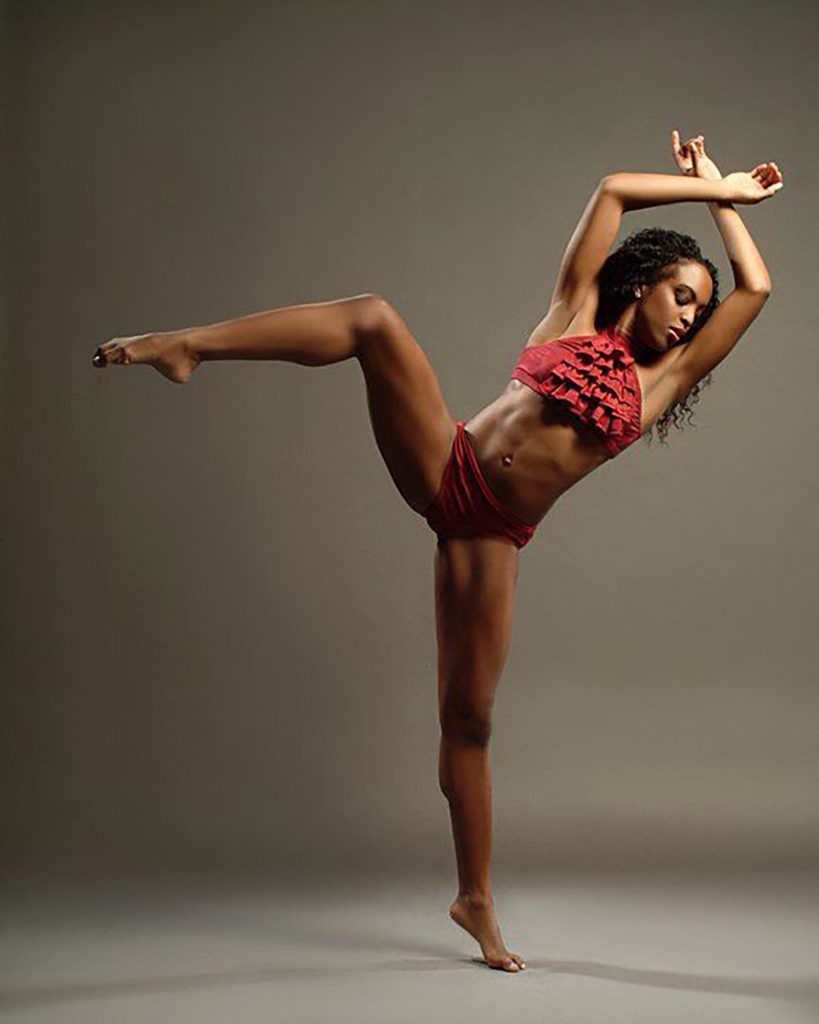

Kiyon Ross

Kiyon Ross is the associate artistic director for Pacific Northwest Ballet, an organization he has been part of since 2001, when he joined the company as a dancer.

One of the biggest things I’ve learned is that you must have a global perspective of your organization to manage people well. That was really my “aha” moment. My job as associate artistic director is to help [artistic director] Peter Boal oversee a larger picture of the organization, and not really get lost in the minutiae. Managers deal with all the details. Peter and I have this forward-looking future view of what we would like to see PNB achieve.

It’s challenging because you must start taking into consideration other people’s views and opinions, other people’s feelings about ideas and projects that you’re bringing forward. And the kernel starts with you as the leader: to bring people in and to get that buy-in. You have to ask, “Where are we going and how do we get there?” “Okay, team, what do we think about this?” It takes practice and patience. It takes having an open mind and an open heart, especially when we’re dealing with the arts.

I consider myself a collaborative leader: I really value the input of the people on my team. It’s harder to bring people in after you’ve made decisions and then say “What do you think?” because this makes it much harder to unwind the decision. My preference is always to bring my team in as soon as possible so we can start having these conversations and unearthing things that I may not be thinking about. What I’m realizing is that as a leader, you don’t really say too much. However, you really need to have good listening skills.

The skills you learn as a choreographer are definitely transferable to being a leader. My first foray into choreography was in 2005, and this was the first time that I stepped into trying to manage a room full of people. You have to have a certain kind of authority over the room—not an oppressive kind of authority, there just needs to be someone running the show. There needs to be someone making decisions, taking the input and leading us to where we need to go.

Now I feel there’s a new generation of dancers who are empowered to use their voices. During my own career I frequently felt I didn’t have a voice in what I was doing. For the generation of dancers that I grew up with, you were seen, not heard.

We have this huge movement towards improved mental health, and this is really important: The only way to know what your dancers are going through is to ask questions and to listen. Once people know they can use their voices, this creates a calmer working environment. People know where they stand. They know they can always get support from directors. They feel part of the organization, and belonging is so important when you’re working for a large arts organization.

My North Star is to leave things better than I found them. I can’t say that enough. The significance of being a Black man in a leadership role in a large ballet company is not lost on me. I know there are a lot of eyes on me, and a lot of expectations. Even still, I’m just focusing on doing good work: Do good work and then everything else will follow.

Clifton Brown

Clifton Brown, who joined the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1999, was recently appointed assistant rehearsal director.

The learning is an ongoing process, like so many things are in life. I’m trying to be aware of how I communicate, rather than taking for granted that there’s common knowledge. Every dancer is an individual, which means there isn’t an instant understanding. I try to find words or imagery to assess where someone is coming from: a place of movement or narrative or intention. I have learned that there’s an interpretation process that’s necessary to help dancers take their next step, get to their next level.

I think about being of service to the dancers and wanting to have a working knowledge of each piece. With some pieces, I know the ins and outs because I’ve performed them. But with the Ailey company, we have so much repertory that it hasn’t been possible to use this approach with every piece. When someone asks something, I have learned to rely on crowdsourcing, or [former director] Judith Jamison or [former associate artistic director] Masazumi Chaya, who worked side by side with Mr. Ailey for so long and knows his work so well. I’m learning to not stall out in those moments of uncertainty and to be resourceful if I don’t have an immediate answer.

Not only does the movement speak, but the whole look of it, its design and its structure are important. As a younger dancer, I was pretty fast with learning choreography. There’s always a dancer or two who knows everybody’s part, and that was me. But, sadly, it’s harder now. If a piece has lots of canons with numbers to remember as far as “I jump on 5 and 12, but in my other role, I jump on 2 and 6,” and dancers are switching parts within one dance, then we have an Excel spreadsheet. This happens for a piece like Aszure Barton’s BUSK, because it’s a lot to remember.

Dancers today have voices and are given spaces where they can be heard. As much as possible, there’s an effort toward dialogue and transparency. I also feel fortunate to be part of the artistic staff with two people who have been doing this for longer than I have. And many dancers in the company have graduated from college. I was 19 when I joined the company, and I was kind of at the tail-end of a generation that started dancing professionally as young as possible. I have no regrets as far as how things worked out for me, but I learned through trial by fire.

I feel there’s a difference in the nature of my two jobs: From dancer-performer, where the focus is on yourself, to being on the other side of the room, which is about being a facilitator. It’s wonderful when dancers can take it upon themselves to figure things out and are kind of open to a participatory process. It’s not a necessity, not the responsibility of the dancer, but something we hope for as rehearsal directors. Matthew Rushing, Ronni Favors and I work as a team, and that has been invaluable: to discuss what’s needed, what’s lacking, what we’re not getting to. And my partner, Earl Mosley, is a choreographer and teacher, and he’s extraordinary.

Janine N. Beckles

Janine N. Beckles, associate artistic director of Philadanco!, continues to perform with the company while also expanding her knowledge of leadership: She is currently enrolled in a master’s degree program in business, with a concentration in leadership, at Southern New Hampshire University.

I’m continuously growing, knowing what my capabilities are and being there for my co-workers. I love being here because I have great guidance: Joan Myers Brown is our founder and is still here as artistic advisor. Ms. Kim Bears-Bailey was promoted to artistic director. I’m not going to lie: The work is hard, but I know how to balance work well.

I double-majored at Southern Methodist University in dance and sociology. After I graduated, I thought I wanted to go to law school, applied and got in, and then realized I wanted to dance. I deferred law school and went straight into dancing with Dallas Black Dance Theatre. I’m still interested in law, and I have had the privilege to work as a legal assistant for eight years for one of our board members, Spencer Wertheimer.

As associate artistic director, I find my legal knowledge comes in handy with contractual agreements. I created a new release form for dancers who want to work as guests with other companies, and I’m very meticulous with contracts for presenters. I also make sure things are appropriate for the company and the venues when we tour.

Black leaders, women leaders in particular, need to stick together and build a support network. They need to start mentoring: Mentorship is the only way the knowledge will be transferred. Leadership is not about an individual act, it’s about helping others.

Based on Joan Myers Brown’s experiences of forming her company, having to go through what she did here in Philadelphia in terms of barriers like sexism and racism, I think, unfortunately, not much has changed. As a dancer, and a woman, in many ways we’ve been taught not to put ourselves out there, to just follow the rules. The dancer mind says, “Stay in your lane!” The leader mind says, “Use your voice!” I have to, sometimes, go against the grain. I’m hesitant, not going to lie. There are plenty of times I want to say something, but I’m scared. But, then, if I don’t, nothing’s going to change.

Helping people within an organization helps the organization grow, like a flower that blossoms. As the dancers’ boss, I have to make sure that everyone is okay. This requires being empathetic, having one-on-ones with dancers, finding out how they’re feeling and asking them, on a daily basis, “What do you need?” “Where do you see yourself going?” “If you ever need anything, I’m here for you. I can be your mentor; I can be your guide.”

Philadanco! has some amazing positives: We’re paid 52 weeks a year; there’s touring on a regular basis. We’ve made the company larger, with nine women and six men, and we hired new dancers last January. We’ve had technical advancements, like giving a new iPad to each dancer. This place is not just where you can start; it’s where you can grow. It’s not a stepping-stone; it’s where you can have your career.

Helanius J. Wilkins

Helanius J. Wilkins is the associate chair and director of dance in the Department of Theatre & Dance at University of Colorado, Boulder. Between 2001 and 2014 he established and directed EDGEWORKS Dance Theater, Washington, DC’s first all-male contemporary dance company of predominantly African American men.

What I’m doing is part of an ongoing process. My current leadership role was not so much about starting something new, but building on the toys, tools, experiences, hardships and successes that reflect my past and that led to the wisdom that I now bring into the spaces that I navigate.

My approach to leadership is anchored in being generous with others. That generosity emerges from giving value to being in and with community. I lean into collaboration and being a team player and trust that answers can be found among the whole. How can I share what I have gained and what I have experienced in ways that can spark curiosity for others to go on their journeys? Leadership, for me, is not about being a fixer or a savior.

I’ve deepened my relationship with patience while keeping my eye on a vision. Leadership in university settings takes place within systems that typically move slowly, and yet tremendous change is happening all the time. A colleague recently reminded me to celebrate the small wins. This feels so important.

Leaders draw on a diverse range of skill sets: communication, the ability to be a team player and the ability to work with care. Communication involves understanding how to read a room, how to access what a space may need and how to match the moment. Being a team player means understanding the multiplicity of ways we define collaboration. Working with care feels important. Care for ourselves so we can function at our fullest and most present. Care as it relates to reciprocity, meaning “How am I operating in a manner that allows for both giving and receiving? How do meaningful exchanges allow us to show up as our best selves for one another?”

I entered the field as a maker first. My work is unique, but my voice is not necessarily about me. It’s about how I create community, senses of belonging and a dynamic spark for others to imagine worlds and landscapes of potentiality. I value belonging and our relationships with environments because I have been in places where I did not feel like I belonged. I take to heart that there are multiple views and perspectives, and my work reflects this.

It’s not an automatic transition from being an artist into a university setting. Being in an R1 institution, I embrace research: It’s part of my job. That said, positions within academia are heavily administrative. There must be a genuine care and enthusiasm for research, teaching and service. All three are required, and not solely for the purposes of one’s own art. Although I’ve been in academia for 20-plus years as an adjunct, visiting professor or guest artist, this is my first tenure-track position. The core values of CU Boulder’s dance program match with mine. We are constantly leaning in with curiosity, and we embrace our successes and strive to build upon them.