How Dance Artists are Fusing ASL With Choreography

For Deaf audiences, watching performances with traditional sign language interpretation can feel like watching a tennis match: Their focus has to toggle between whatever is happening onstage and the interpreter, often off to the side, who might be communicating what the music sounds like or what’s being said. That’s if the performance even has an interpreter, which all too often is not the case.

But attend a Company 360 Dance Theatre performance and the tables are turned. The Fredericksburg, Virginia–based company, led by choreographer Bailey Anne Vincent, who is Deaf, incorporates American Sign Language into all its productions. “If you’re a Deaf person, you’re in on the story more than a hearing person,” says Vincent.

For Vincent, using ASL in her choreography—which might mean incorporating a sign to emphasize an emotion a character is feeling, or to communicate what a lyric is saying—is both an artistic choice and an accessibility-related one. Though her audience is mostly hearing, “I still try to approach all our shows assuming there might be someone who is Deaf in the audience,” she says. But it’s also just a natural extension of the fact that ASL is Vincent’s preferred language. “When I choreograph, the way that my mind thinks is in my own language,” she says. “So even if I don’t want it to, sign finds its way into whatever I’m choreographing. It can’t really be extracted.”

Deaf actress and dancer Alexandria Wailes feels similarly. “Dance and using ASL are both so embedded in who I am, as part of my identity,” says Wailes through an interpreter. “I can’t really separate one from the other.”

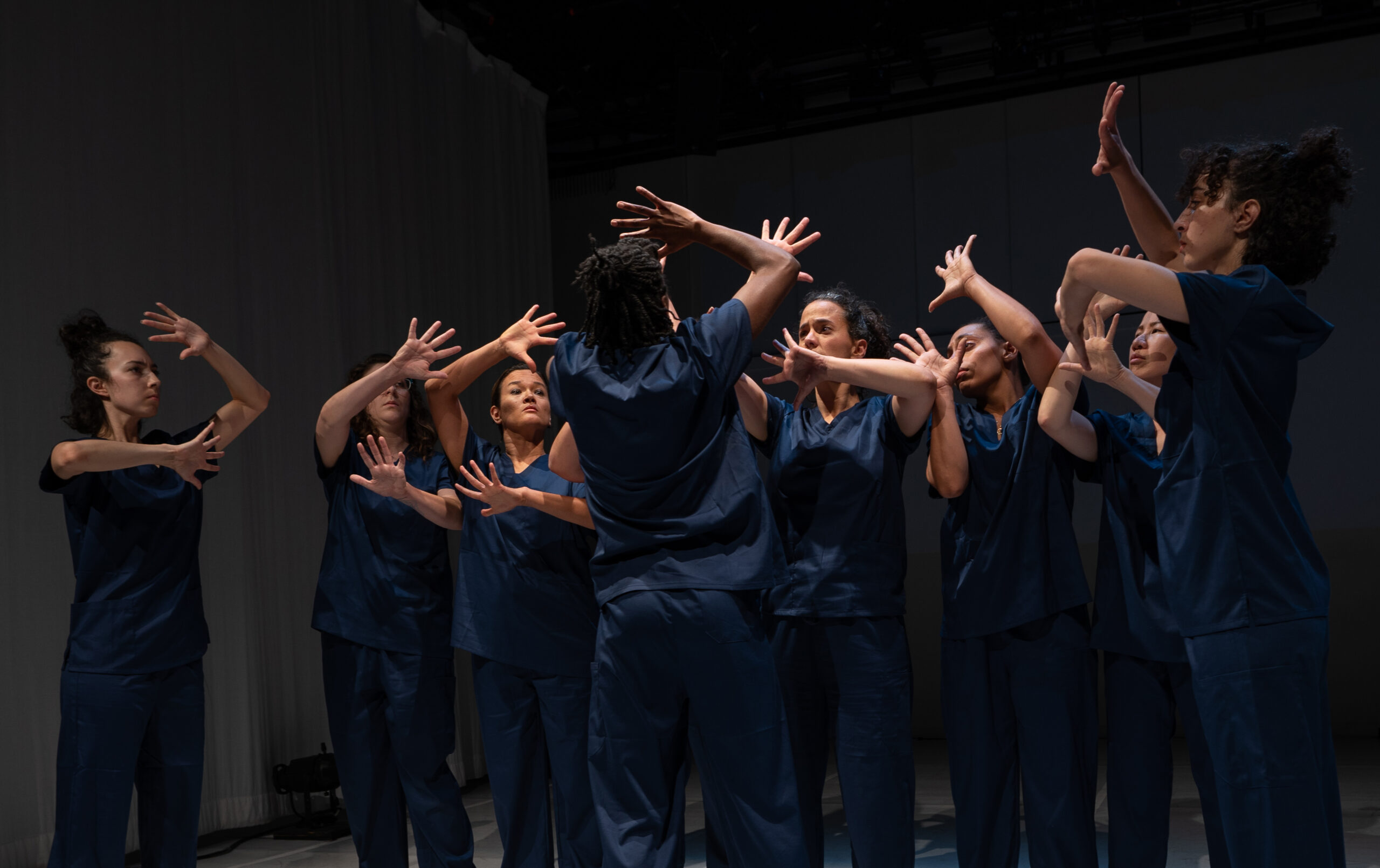

For artists, like Vincent and Wailes, who are fluent in both the actual language of ASL and the proverbial one of dance, the intersection of the two embodied forms offers limitless creative potential, and the vital opportunity to make accessibility efforts less perfunctory and more integrated and enriching. Though incorporating ASL into choreographic work is not a new phenomenon—Deaf-led companies and Deaf artists have long done it—it’s becoming increasingly common on increasingly mainstream stages.

To get a sense of the deepening relationship between dance and ASL, look at choreographer and performer Brandon Kazen-Maddox’s career thus far. A GODA (grandchild of Deaf adults) and native ASL signer, Kazen-Maddox was long one of the New York City performing arts scene’s go-to interpreters, a reliable presence at performances, talkbacks, and more.

But in 2019, choreographer Kayla Hamilton asked Kazen-Maddox to join her New York Live Arts Fresh Tracks piece not as an interpreter but as an artist. “She asked me to represent all sounds in sign language, and also use my body as a dancer,” says Kazen-Maddox. “It was the most mind-shifting thing for me, because I was seen as an artist and a dancer and a performer, and was also representing in sign language everything that was happening.”

The experience was the beginning of a shift in Kazen-Maddox’s career, away from simply facilitating communication between Deaf and hearing individuals as an interpreter and towards an emerging genre Kazen-Maddox calls “American Sign Language dance theater.” But it was also indicative of a wider shift in the performing arts, one that is more artistically fulfilling for Deaf and ASL-fluent artists and that also repositions accessibility: Rather than something tacked on to and separate from the performance, it is something deeply ingrained and integrated.

Always key to this work, says Wailes: Deaf or Hard of Hearing performers who are “bilingual” in dance and ASL. “If you’re trying to be more inclusive, great,” she says. “Who are the people who are onstage? What are their lived experiences and how does this reveal itself in the work? We should continue to push towards the embracing of more people who have never been welcomed in these spaces.”

The Question of the Audience: Who Is It For?

Until recently, Betsy Quillen experienced performances for Deaf audiences and hearing audiences separately. “It’s one or the other—it’s very isolated,” says Quillen, who is a Hard of Hearing actor and theater director. “There are Deaf shows, and there are hearing shows, and very rarely do the two feel comfortable together.”

So when choreographer William Smith asked Quillen to collaborate with him on a piece for Roanoke Ballet Theatre that incorporated sign language, they had a clear goal: to make something that both Deaf and hearing audiences could understand and enjoy. “My specific role was making sure that Deaf eyes would understand it, and that we were making our Deaf audiences feel welcomed and included and respected,” says Quillen. “But we also made sure to show our hearing audience that this piece is made even more beautiful because we’ve included the Deaf audiences—that all of this ASL in every part of the production is enhancing the experience for everybody in the audience.”

Roanoke Ballet Theatre.

The question of who a production is for, and how many in the audience will be fluent in ASL, isn’t always a straightforward one, says Alexandria Wailes, a Deaf dancer who blended dance and ASL in the recent Broadway revival of for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. “Most of the time, it’s going to be people who don’t know ASL,” she says through an interpreter. “So what does that mean, in terms of what I’m sharing? I’m very aware that most of the audience is probably not going to quickly understand what I am saying. I just have to express it.”

But even that imperfect understanding can spur new ways of thinking. “The reactions I received from a lot of people after shows—their brains had shifted,” says Wailes. “For me, that was really exciting, because it means my work is encouraging people to think outside of what they’re used to experiencing with dance and signing.”

“ASL Is a Language, Not Just Something You Look At”

For artists and audiences who are not fluent in ASL, signs can sometimes be indistinguishable from choreography. And when hearing artists and audiences value how signs look over what they mean, the fusion of dance and ASL can become offensive rather than enriching. Antoine Hunter PurpleFireCrow, founder and director of Urban Jazz Dance Company and the Bay Area International Deaf Dance Festival, gives the example of a hearing choreographer asking him to “reverse” a sign because it would look cool, which then made it meaningless or changed it into a distasteful word.

“When people who are not native signers see ASL incorporated with movement, they’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s so beautiful,’ ” says Alexandria Wailes, a Deaf dancer and actor, through an interpreter. “Which is valid in its own right, but ASL is a language that is tied to culture, communities, and history. It’s not just something that you look at or do because it feels cool and it’s beautiful.”

That doesn’t mean ASL always has to be used literally, or that it can’t be an opportunity for experimentation. In fact, the expectation that ASL be completely legible in an artistic setting can limit Deaf artists, when there’s no similar expectation that spoken language in performance always be logical or straightforward. (For instance, it’s not uncommon for performers to say absurd sentences, or experiment with strange deliveries.)

“The forcing of it to be legible, or to be understood, is not allowing for the people who live it to speak their truth,” says Yusha-Marie Sorzano, a Hard of Hearing choreographer who collaborated on a 2020 solo for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater performer Samantha Figgins that incorporated ASL.

For Hunter, this might look like using signs that are actually the total opposite of what the lyrics of the song are conveying. “As with any other language, ASL can be used poetically, rhythmically, artistically, metaphorically,” shares Hunter.

“I think it’s really beautiful when you begin to weave languages, because in the weaving comes the new word,” Sorzano says. “How fascinating is it that a sign that represents ‘I am’ can be woven next to a renversé? And does that become a new way of being ‘I am’? There’s this beauty in what happens when you build something new.”