Auditioning for Fosse

It was the summer of 1972 in New York City. I was young, and boy was I in love! I was in love with dance. I wanted so much to be good, and to be able to harness all those unearthly structures and graces. It was gripping my soul and my heart. I was also scared to death!

I was auditioning!

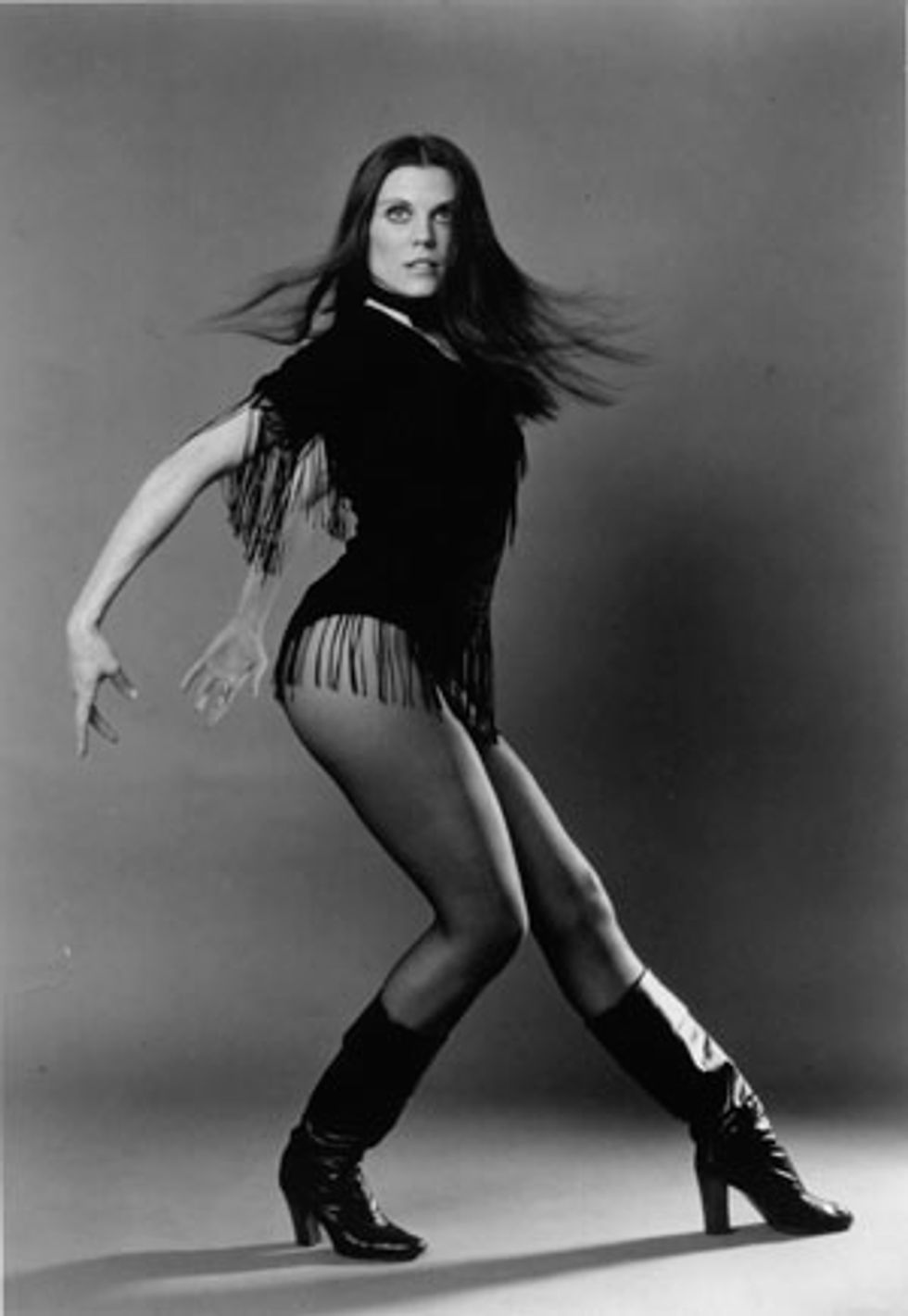

I was auditioning for the Broadway show Pippin, directed and choreographed by Bob Fosse, and I wondered if I would be any good. Quite a while ago I knew if I was ever to get used to this process I’d have to go to a lot of auditions and not expect anything, but try to enjoy myself and, hopefully, get involved in the work and concentrate. I also began to notice what certain choreographers liked. Bob Fosse liked the color black. So I wore black that day, and high heels, too. I wanted to last at least long enough to be able to dance some of his work.

Every time I saw his pieces I was quietly amazed, as if a whisper had knocked me over. When I saw some of his numbers on TV or in the movies, I was overwhelmed by their elegance, wit, and charm. When those magical dances were over, I was stunned—they were so good! And his dancers—they were wildly special and individual. I wondered what they were thinking while they danced. It seemed to me that their thoughts were mysterious and filled with a lot of stuff that shone from behind their eyes. Whatever that stuff was, it was somehow what I myself felt–like an unwritten code. I was totally connected. I wanted to be like those dancers and capture that connection forever. I wanted to dance those steps and in that style. I wanted the privilege! Everything in my body reached for it.

So there I was at the Imperial Theater in my black tights and high heels. The first combination was ballet. I really liked the steps and the smart way it showed not only ballet technique, but percussive rhythms as well. There were lots of turns, jumps, syncopation, quick changes of direction, and lyric jazz touches juxtaposed against the classical style. Fascinating!

I was asked to remain for the next combination. I had made the first cut! The next dance was absolutely great and so different. It started with an adagio that was like a jazz version of Robbins’ Afternoon of a Faun. The music was very romantic, in the style of Erik Satie’s Trois Gymnopedies. I was surprised that Mr. Fosse picked that kind of music, as he was not particularly known for romanticism. But romantic it was. Our feet and legs were in a turned-in fourth position, torso bent over parallel to the floor, arms in fourth position mimicking the legs. He said it should look like hieroglyphics. On the first two chords of music we contracted and released our backs.

And so the dance went on with delicate body isolations as we moved across the stage. Beautiful arms that waved, sometimes behind our backs, sometimes by our sides. A lot of the port de bras was turned-in in various ways, and the upper body would tilt so one side of the torso was hanging while the other side did the movement. We were always working at least two parts of our bodies at once, if not more–kind of like the interior workings of a beautiful clock. There were turned-in passes with hip isolations as you balanced on half-pointe and then fell into the next movement—always with lovely arms, sustained bends, and unique shouldering.

What was also fabulous, and enabled me to overcome my self-consciousness about the technique and all those steps, was that all of our movements were to be enacted toward an imaginary young man (Pippin). As we moved, so he would move, changing our focus and direction. Mr. Fosse told us that the character was an innocent youth searching for perfection—in this case a woman. We were what he was looking for—the ideal.

I started to become so involved. All the steps made total sense. They were our vocabulary, our “speech” to the young man. At one point we were doing one of Mr. Fosse’s classic movements—arms that were placed behind our backs and waved as if they were pushing water back and forth. He said, “I want soft-boiled-egg hands!” Oh woe! I didn’t know what that meant. But he explained, “It’s as if you are holding soft-boiled eggs at the curve of your fingers when they make a loose fist. But the eggs have no shell: they’re just fragile, quivering things that must not be broken while you undulate your hands and arms.”

Well, with that, the movement took on such care and dangerous grace. Everything was completely unreal now. Not only was I involved with the steps and my intentions toward Pippin, but I was becoming very aware of my character’s own power and the delicate veneer on which it rested. “Fragile weight” is what Mr. Fosse called it. We were working in a paradox. We were a flesh-and-blood fantasy. We were perfectly imperfect. Now all the other phrases and steps to come—”busted legs,” “broken doll,” “tea-cup fingers,” “false drama,” “tacit power,” and “loud stillness”—not only felt good to do, but I knew why I was doing them! It made sense. There were no questions. All was answered.

I had made the second cut!

We learned a new combination with lots of new steps, like “the mess around,” the oddly beguiling “slow-motion slop,” “pistons,” “dusting the piano bench,” “amoebas,” “East Indian hands,” “body ripple,” “chugs,” “Xs and Os,” “layouts,” and “the Joe Frisco.” They were the culmination of taking something that looked broken and making it perfect. And these movements had to be extremely clean and tastefully done. On top of all that, we had to improvise an imaginary ball or balloon that we tossed up in the air and caught with our hands, feet, arms, knees, and so on, all the while incorporating it into the original combination in some way.

What a wild trip! I really wanted to do this dance because the dancers became an inventive and integral part of the piece. I had to invest even more! I had to take chances! This process was so intense!

Mr. Fosse would guide us, encourage us, help us if we needed it. He told us when the improvisation was right and within the framework of the number, and he would also tell us when we were wrong. He watched our reactions both when we were praised and when we were corrected. He wanted to know if we trusted him. This was the most important criterion of them all. Trust was a big thing with Bob Fosse. Big.

I couldn’t believe how much at ease I began to feel, and with total concentration. I lost all sense of being at an audition. In the past, auditions had made me aware of everything that was around me, like the other dancers who always seemed so self-assured, so good at what they did, and were so utterly beautiful. Me? I was always looking at the reactions of the choreographer, music director, assistants, producers, authors, and everyone who was watching. But Bob Fosse was right up onstage working side by side with us, saying, “OK, let’s try this… Why don’t we turn here?… Let me change that move for you… Yes, I like that. You look good… No, I’m wrong. Let’s try something else… Here, this is another way for you to create the rhythm to accomplish that step… Keep it elegant… Let me help you.”

He was so nice. And he really looked cool dancing.

It was personal now. Trust had become a pan of the whole process, and nervousness and fear disappeared. He could tell if we trusted him or not. And me? I trusted him completely. During those precious hours on that stage, I felt that I belonged. Even if I didn’t get this show, I’d had the best day of my life. It’s rare to go to an audition and realize that you have walked away richer than before, whatever the outcome. I had learned so much. I felt a part of something very special. I felt at home and content, as if I had purpose in my life.

For the first time in a long time of loneliness, I felt I belonged! This is what I loved! I loved dancing! My heart was about to break! And I was falling in love with Mr. Fosse—with Bob.

It was the summer of 1972 in New York City. And I was asked to come back the next day for final auditions.