Ayodele Casel Is Proving Tap’s Power to Speak to Social Justice—and Spark Serious Joy

In fall 2016, Ayodele Casel received a call from the director of Spoleto Festival USA, asking if she could present a show as part of its summer 2017 programming in Charleston, South Carolina. She didn’t hesitate to say yes. Although she had recently premiered a new work, While I Have the Floor, and even performed it at a star-studded fundraiser for then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, the piece was only seven minutes—hardly a full-length show.

Still, she remembered a promise she had made to herself two years earlier, after the 2015 crash of Germanwings Flight 9525. A frequent flier, she was struck by the story of the co-pilot who had deliberately maneuvered the plane into a mountainside, killing everyone on board.

“When I saw that story, I had been feeling particularly unsatisfied with my level of artistic expression,” she says. She thought: What if I’d been on that plane? What would I feel on the way down? What would I think about everything that I wanted to do and didn’t?

“Something in me broke open,” she says. From that moment on, she promised herself she would follow her impulses as authentically as possible. “Since then I’ve been constantly asked to work in spaces and with people that I love and to live my artistic life without compromise. It’s the most incredible freedom. I wish everyone could experience it.”

Audiences certainly experienced some of it that summer when her Spoleto performances were sold out. The New York Times declared that she was “having her moment.” But to the tap community, who had already known her for two decades as a teacher, performer, choreographer and producer, her moment had started long before. The rest of the world was just catching up.

Casel, 45, says only half-jokingly that she hasn’t taken off her tap shoes since she started dancing. Born in the Bronx and raised in Puerto Rico, she first took tap as a movement elective while majoring in acting at New York University. Just a few years later, she was dancing with Savion Glover’s Not Your Ordinary Tappers, the only female in the ensemble. She found her voice as a soloist, performing at New York City’s Triad Theatre in 1999 and Joe’s Pub in 2000. The themes that would come to define her work were already present: dancing to Latin music, honoring her Puerto Rican roots, and incorporating narratives and spoken word.

As someone who became interested in mining the possibilities of tap and storytelling, she could not have picked a better time: Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, a blend of tap and spoken word that honored Black history, had just made waves with its Tony Award–winning run on Broadway.

But even as tap was at its apex during the ’90s, something was still missing for Casel.

“I was getting weary of audiences just commenting on the virtuosity of our footwork, but nothing else,” she says. “I wanted to humanize tap dancers and reveal who we are as people, as human beings, and why we do what we do.”

That desire resulted in the first incarnation of Diary of a Tap Dancer in 2005, the beginning of her exploration of presenting tap in a narrative form that included the voices and experiences of the dancers. As a woman of color, Casel was alarmed at how little documentation there was of the lives and careers of female tap dancers, such as Jeni LeGon, Alice Whitman and Lois Bright. She wanted to share their stories and give voice to their influences. “I also thought, Wow, should I not tell my own story, it will be no different than those women,” she says.

After 2006, when she appeared on the cover of Dance Spirit and co-starred in Imagine Tap! in Chicago, it may have seemed that her story was, as she puts it, “lost in the shuffle.” But although she wasn’t receiving as much attention, she never stopped working. She toured with L.A. Dance Magic, co-created the popular online resource Operation: Tap and co-founded Original Tap House, a performance and rehearsal space for artists in the Bronx.

“My work is independent of opportunities that come and go,” she says. “The difference between me now and me at 25 is that now I don’t just think, When’s my next gig? I see the power of this art form to speak to social justice, race, identity, politics.”

As a 2018–19 artist in residence at Harvard, she presented research, taught and performed on campus, and began a community project around sharing and archiving personal narratives. Then as a 2019–20 fellow at the university’s Radcliffe Institute, she began researching and developing Diary of a Tap Dancer: The Women. The next installment of her ongoing project, it focuses on the voices and lives of Black women tap dancers.

Being in an interdisciplinary setting at Harvard, surrounded and respected by great thinkers, left an indelible impression. “It wasn’t the experience of the average tap dancer,” she says, “but it should be. Tap dancers should be included in conversations about all things culture, beyond just dance.”

In early 2018, Casel participated in a conversation on “Decolonizing Dance,” hosted by Gibney in New York City. While proud of the attention that Dorrance Dance had been receiving, she voiced concerns that Black tap dancers weren’t getting the same kinds of opportunities.

“I didn’t speak with the intention of being combative,” she says. “I want to illuminate and forge a path for more equity in response to the injustices I see about who gets to dance and who doesn’t, what presenters find appealing and not appealing.”

In the audience was The Joyce’s new director of programming, Aaron Mattocks, who made a point to look her up online the next morning. “I was completely enthralled with her magical combination of uplifting joy, her infectious smile, her rhythm and her groove, her presence, and most importantly, her vulnerability and honesty,” he says. “Her story had an urgency and a passion that I knew would connect with audiences.”

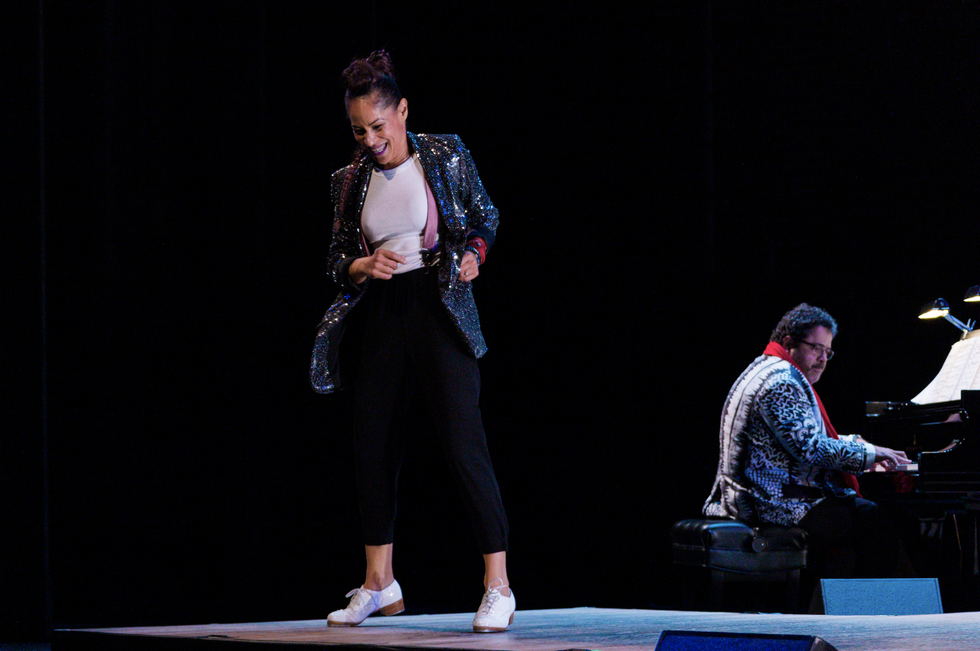

In September 2019, Casel was featured in The Joyce’s tap-filled fall schedule in a full-length show with Arturo O’Farrill, the Grammy Award–winning bandleader of the Afro Latin Jazz Orchestra. “She is a listener, a contributor,” says O’Farrill, “and a true partner.”

The two had also performed together in ¡Adelante, Cuba!, a celebration of Afro-Cuban and Latino music and dance at New York City Center. Casel is a frequent collaborator with the venue, which had previously hired her to perform in its Fall for Dance festival and to choreograph a revival of the musical Really Rosie. She was also the featured artist of the inaugural City Center On the Move program last year, in which Casel presented a lecture-demonstration in each of the city’s five boroughs. Even some of Casel’s longtime neighbors, who had never seen her dance, attended. Starting July 14, she is presenting a series of weekly tap performances through New York City Center Live @ Home.

“I clearly see my purpose now,” she says. “Dance is my entry point to make connections with people and spread joy.”

That’s exactly what she does with A BroaderWay Foundation, which teaches leadership skills through the arts to young women ages 9 to 17 from New York City charter schools. She directs the graduate program, mentoring girls who have gone through the experience, while her wife and collaborator Torya Beard serves as the foundation’s executive director.

“Ayodele brings the legacy of her heroes into every space she occupies,” says Luke Hickey, who often dances with Casel. “She is fearless, but also welcoming to everyone she invites into her process.”

In a particularly poignant moment in the first version of While I Have the Floor, Casel wondered aloud whether her story would be forgotten, or whether future generations would recognize her name. Today, she is having more than just a moment. She is cementing her legacy.