Even Crystal Pite Gets Nervous Before a First Rehearsal

Crystal Pite is a busy woman.

While her company, Kidd Pivot, toured the globe recently performing Betroffenheit—its acclaimed collaboration with Jonathon Young and fellow Canadians Electric Company Theatre—Pite herself launched three productions at three of the world’s foremost dance companies: Nederlands Dans Theater (The Statement, February 2016), the Paris Opéra Ballet (The Seasons’ Canon, fall 2016), and London’s Royal Ballet (Flight Pattern, spring 2017).

Increasingly, her projects are at a scale to match their prestige, with roles for as many as 54 dancers (The Seasons’ Canon) or, in the case of Polaris, more than 60. We caught up with Pite while she was at home in Vancouver.

It must be nice to be home. You’ve been quite busy.

It was intense, but wonderful. I kept pinching myself and thinking, Is this for real? After every hurdle, I had to just say, “Check. Done. Survived that. What’s next?”

Does it still feel like the first day of school, to begin with a company that’s new to you?

On my way up to the Paris Opéra studios I was so nervous! Literally shaking. But within about eight minutes, I was reminded, “Oh, yeah: This is the same old thing. It’s just dancers in a studio, dancing.” [Laughs]

Crystal Pite rehearsing with Paris Opera Ballet dancers. Photos by Julien Benhamou, courtesy POB

It must’ve helped that the other pieces on that program were contemporary.

I always benefit from being at a company during or right after the dancers have been immersed in contemporary work. They had just recently worked with Bill Forsythe in Paris when I started The Seasons’ Canon; in London, for Flight Pattern, I had the benefit of following Hofesh Shechter.

I noticed that there was an openness, a willingness, a kind of articulation and understanding in their bodies that maybe would not have been there otherwise. Dancers just keep growing, keep gaining more information and dimension; the more people they work with, the better they get. It really is that simple.

True, but the body can only adapt so quickly.

That’s an important point too. When I was in London, they were with me during the day but performing The Sleeping Beauty at night. I would literally have dancers running into the studio for my rehearsals and taking their pointe shoes off at the same time—hopping in on one foot, shimmying out of a practice tutu, throwing on a pair of socks and sliding into the center of the room into some deep, deep position, with their weight completely dropped and a rounded spine.

Royal Ballet dancers in Flight Pattern. Photo by Tristram Kenton, courtesy Royal Opera House

The Royal Ballet’s dancers and the artists of the Paris Opéra are like the Swiss Army knives of dancers.

That’s such a good way to put it. Which part of the Swiss Army knife do you think I am? The toothpick, maybe? The scissors? Oh, I’m the corkscrew, aren’t I? [Laughs]

What do you fear?

Laziness, I suppose. That doesn’t mean I’m not willing to sit with an idea for a while and give it time to evolve if it needs to, but laziness—complacency—is something else. It would be easy at this point for me to rely on what I already know. But I can’t allow myself to be lazy.

What are you reading?

Jonathon Young gave me these great books by Robert Bringhurst; one of them is called Everywhere Being is Dancing: Twenty Pieces of Thinking. He has beautiful things to say about polyphony and polyphonic music, which have to do with coexisting differences and equal valuation of all voices.

There’s something profound there, something to aspire to, that polyphony is possible, beautiful—and demanding. Worth striving for in our work and in our world.

Where are you today in terms of collaborating on new choreography and music at the same time, versus interpreting a score that already exists?

I really like working with existing music as a script, following its lead and dreaming of how I might bring it to life inside a body. I also love the experience of creating work together in parallel, from the first impulse right through to the very end. With a new work, it’s a lot more work to build something from scratch, but that also leaves space for new discoveries and being nimble for new decisions. This month I have a new creation at NDT to the music of Caroline Shaw, who wrote an incredible piece for eight voices called Partita.

A theme that’s emerged for me, especially in your bigger pieces, is that of the individual within the group; of the ensemble as a “body” of its own.

There’s something energizing in that tension. It stems from my interest in connection, my desire to connect with the people I’m working with, for them to connect to each other, and then, also, for them to connect to the audience. I want to cultivate the sense that we’re all one and that we’re all connected.

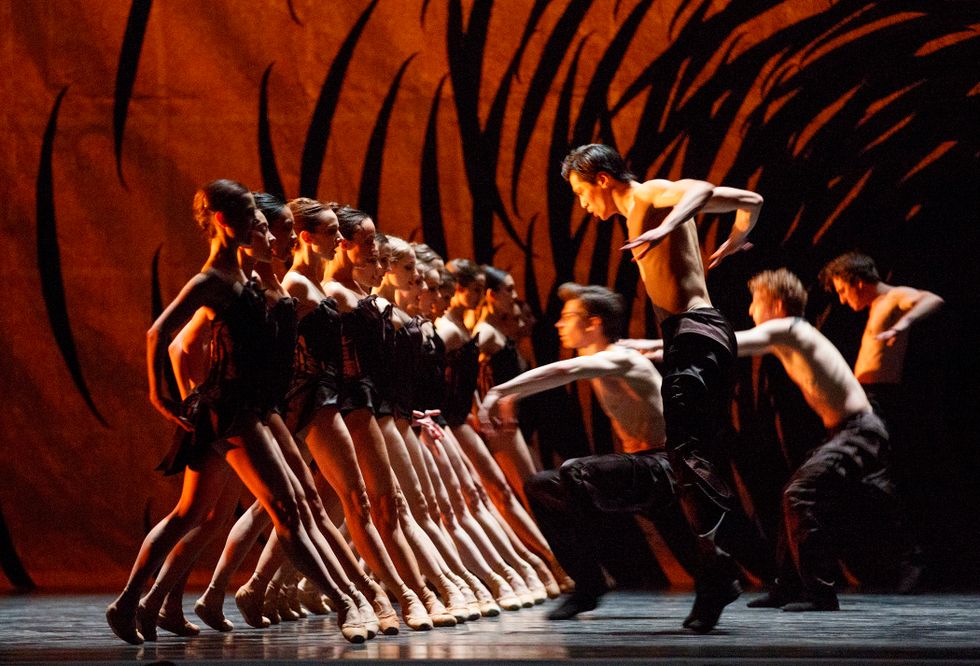

National Ballet of Canada in Emergence. Photo by Bruce Zinger, courtesy NBoC

As in nature. Vancouver is so beautiful—do you consider yourself outdoorsy?

I should do something sporty. It might be time for me to try rock climbing or swimming or martial arts or something—to change it up. I’m in this weird limbo, no-man’s-land with my body, where I feel like I’ve lost touch and connection with my dancing self, and feel like I have to rediscover my relationship with the physical in a new way, or in a parallel way. Maybe skiing—cross-country, though. Not downhill. I don’t like to go too fast.

Anything we should keep an eye out for next season?

I’m looking forward to Revisor, which Kidd Pivot premieres in February 2019 in Vancouver. It bubbles away as I go about my day.