As Archives Become More Accessible, More Dancers Are Diving in to Research the History Behind their Roles

Paul Taylor’s Post Meridian was last performed 30 years ago, which is well before any of the company’s current dancers joined Paul Taylor Dance Company. In fact, it’s before some of the dancers were even born. Every step and extreme angle of the body in the dream-like world of the 1965 work will be fine-tuned in the studio for PTDC’s upcoming Lincoln Center season. However, the Taylor archive is where Post Meridian began for Eran Bugge.

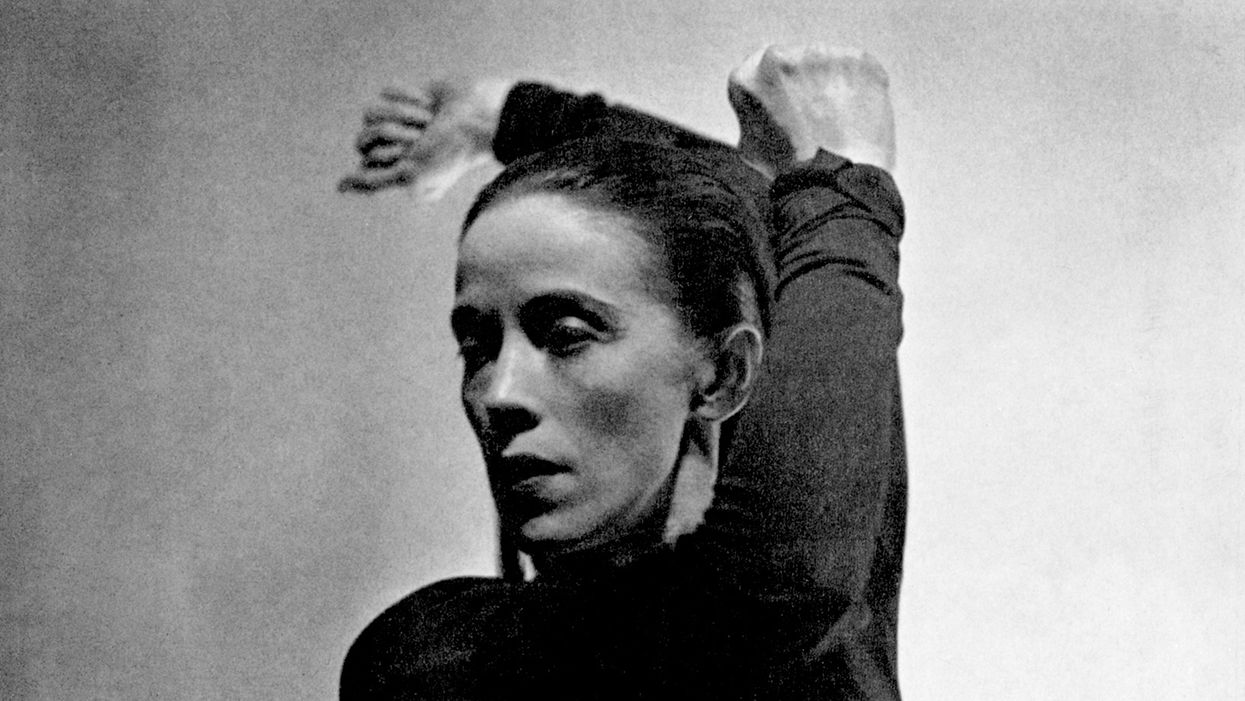

Paul Taylor Dance Company in Post Meridian. L-R: Jane Kominsky, Carolyn Adams, Eileen Croplet, Senta Driver and Danny Williams Grossman

Jack Mitchell, Courtesy PTDC

By immersing themselves in the history of the choreography, through photographs, notations and video, dancers can perform important works like these with more impact. “The dances have so much detail in them,” Bugge explains. “So it is always fun to go back and say, ‘Oh my gosh I never noticed this tiny hand gesture.'”

A dancer with PTDC since 2005, Bugge has worked in the company’s video archives since 2008 when Paul Taylor personally asked her to take on the responsibility. Some years ago, she was the first to identify and digitize several tapes of Post Meridian for their archives. “At that time, everything was a little less accessible in a lot of ways,” she says. “I was all by myself in this back room with all the videos and I just got to watch everything.”

The digitized films and organized inventory system have made these videos a regular and crucial part of the rehearsal process. When learning a role, the dancers always reference past performances—in the case of Post Meridian, looking back decades—which encourages discussion about the incredibly nuanced choreography.

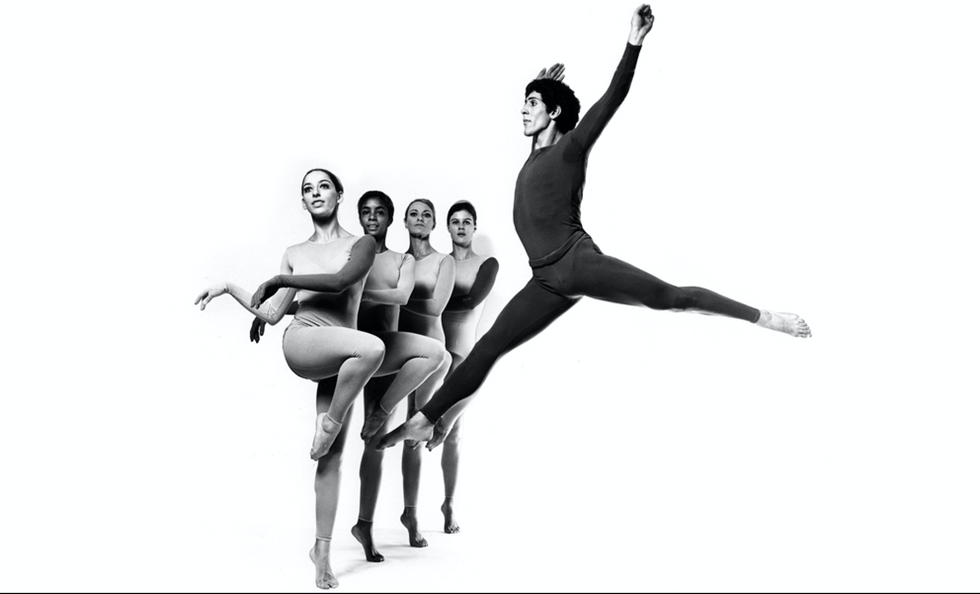

Xin Ying, a principal with Martha Graham Dance Company, also turns to her company’s archive for debuts, and she even visits when returning to something familiar. By referencing stunning black and white photos, literature and videos (films dating back from the 1930s have all been digitized), she is able to explore the impulse behind each movement.

Xin was recently in the Graham archive researching Chronicle (1936) ahead of Fall for Dance. She has danced this masterpiece before, but she’s always striving to reveal more layers. “You get a lot of information in the archives, and especially when it’s being passed down through the generations,” she says, “I always want to go back to see the original. See what was Graham’s intention, what was she thinking?”

Martha Graham Resources is located in the same building as the company studios, and contains a vast collection of materials—among them are rehearsal and performance videos, photographs, notations, interviews, audio, programs and revelatory early technique tutorials voiced by Graham. Her original costume from Episodes: Part I (1959), a darkly elegant and imposing gown, is poised towards the back of the room.

Research, guided by Oliver Tobin (who has been overseeing Graham Resources for the past four years), is an important part of company life at every rank. Director Janet Eilber encourages dancers and choreographers to utilize the collection, and time is specifically designated for Graham Resources on the dancers’ schedules by rehearsal director Denise Vale. These hours in the archive are so constructive that many dancers carve out their own additional moments to visit as well.

This process has been important to Xin’s own development and rise within the company. “I think that’s the only way to translate the character well—you have to go study it,” she says. When preparing for a role she’ll find time to read the original Greek plays and myths, channeling Graham’s own interest in iconic epics, like Cave of the Heart (1946) and the chilling and agonizing pain of characters like Medea.

Archived materials can also be a powerful source of inspiration for choreographers. Pam Tanowitz, who has created works for major companies including The Royal Ballet, New York City Ballet and PTDC, spent time in Graham Resources while working on Untitled (Souvenir) for the Graham company.

Her favorite spot in New York City is the dance division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. But not everything that informs Tanowitz’s choreographic vision is found in films and books. Earlier in her career while working at New York City Center she was able to watch Paul Taylor in action during dress rehearsals, and companies like Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. She’s held on tightly to these experiences.

“I just love dance history,” says Tanowitz. “So I read, go to the library, and see as much as possible. It’s part of my life work and deep love of dance. It’s integrated into all my work for the past 25 years.”

For Bugge, the research for Post Meridian will continue up until final touches with the rehearsal director and mentors, including former company members like Sharon Kinney, who originated the role Bugge will dance. Each performance is an opportunity to sharpen her instincts. “We’re so lucky because we have such a rich history, and you can see many interpretations of the same role. Having all those options to inspire you is really exciting.”