How to Make Even Your Wildest Costumes Work For You

Dancer Brittany Parks has worn a lot of costumes in her career: She’s performed in wedding dresses and giant dinosaur heads on “Glee,” and donned period looks for shows like “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” and Broadway’s Shuffle Along. But embodying a dancing poop emoji for the Disney Channel show “Just Roll with It”—and performing on a stage that was covered in slime—was probably the craziest.

“It was this giant fabric that they put over us, but we were glamorous poop,” Parks says. “We had long legs, nice tights and nice heels, jewels and diamonds—and then literally poop emoji. We were doing ballet moves, and could barely move our arms.”

Courtesy Parks

Elaborate costumes might create stunning (or hilarious) effects onstage, but they aren’t always the easiest to move in. Whether it’s a giant headpiece, a fluffy bear suit, a long train or tight pleather pants, costumes can present all kinds of unusual challenges for dancers. With some key strategies, you can find that balance between adjusting to the specifics of the costume and not letting it disrupt your movement or prevent you from dancing your best.

Adjusting Your Movement

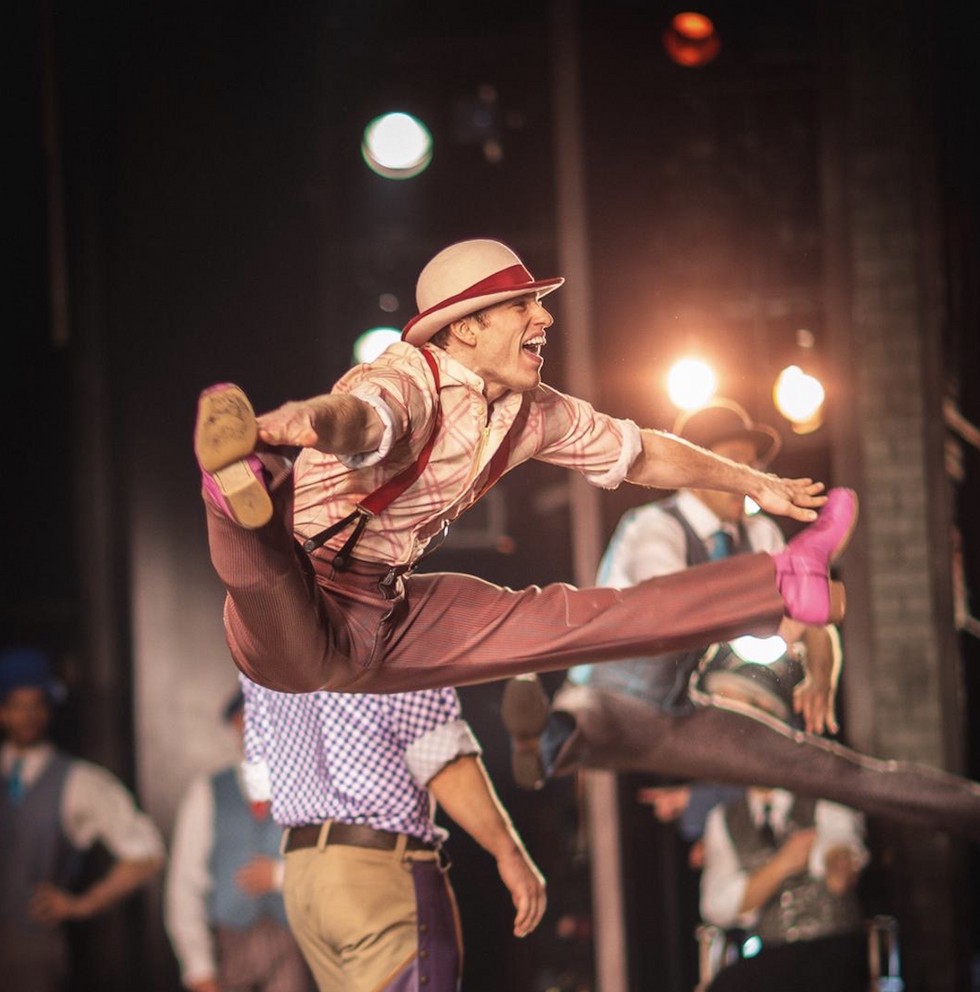

With something that affects your ability to see or throws off your center of gravity, like a mask or headpiece, it can mean recalibrating the simplest things. When Miami City Ballet corps dancer Bradley Dunlap played Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he wore a giant manatee head. (In MCB’s version of the ballet, Bottom gets turned into a Florida manatee instead of a donkey.)

To adjust to the large mask, he had to change where he held his head and placed his gaze—when he looked straight ahead as he normally would, the manatee appeared to be sticking his nose in the air. “With the way the mask fit, I had to look down the whole time,” Dunlap says. “Titania has a skirt on, and I would make sure that I was partnering her and looking at the bottom of that skirt.”

The Timing Issue

The challenges increase when you have limited time to rehearse with the costume, or don’t even see it until dress rehearsal. For “Just Roll with It,” Parks and her three fellow dancers had four or five hours of rehearsal to practice with the poop emoji outfits before the live show aired. They had only two costumes available, so the dancers switched off wearing them and worked on troubleshooting some of the most difficult parts of the choreography, like floorwork.

“There was a point where they wanted to get an overhead shot, so they wanted us to go to the ground and do all this legwork, and we had to figure out how to get down to the floor,” Parks says.

Courtesy Parks

Whenever possible, Parks requests extra rehearsal with challenging costumes. On the set of the movie Teen Beach 2, for instance, during a number that involved zipping and unzipping a leather jacket, she asked the choreographer for more time practicing with the jackets, to prevent snags like stuck zippers.

For Wil Geary, who’s danced in Cirque du Soleil’s VOLTA and the Hamburg production of Paramour, spending even a little extra time with a new costume immediately before going onstage helps him feel more prepared. He’ll get dressed earlier than he typically would to make sure everything feels good, and to take note of anything that could come unzipped or undone during the show. He also thinks about how to make challenges work with him.

“Usually by looking at a costume I kind of know what my limitations are—like, ‘Okay, I probably can’t kick all the way to my head, but I can still find a way to elongate that, even if it’s just with my arms,’ ” he says.

Limitations as Opportunities

Parks tries to focus most of her energy on the dance itself. “I try to make the costume a part of the dance instead of letting that added element take over what’s happening,” she says. “Costumes can be distracting, but you embrace it.”

Limitations can provide opportunities to think more carefully about your character. As the manatee, Dunlap found that his movements had to be even more exaggerated than usual to convey character through such a large mask. He found it helpful to think of his facial expressions as originating from his chest and radiating outward, so his body could help illustrate them.

“Then I feel like it sort of shoots off to all the limbs, because I do lose the ability to give information with facial expressions,” he says.

He also focused attention on details he had more control over. He watched videos of manatees and thought about giving his movement a slower, heavier quality. Without going beyond approved alterations to the Balanchine choreography, he made his arms and hands act more manatee-like. “We did more open-palmed gestures that looked more like fins, as opposed to legs and hooves,” he says.

Alexander Iziliaev, Courtesy Miami City Ballet

When to Speak Up

Geary stresses that he always tries to do at least one full run in a costume before expressing any doubts. But sometimes it might be appropriate to raise concerns with the wardrobe team.

“If it’s a matter of safety or if it significantly limits my abilities, then I do try to bring it up and see if there’s a solution,” Geary says. For Paramour‘s Western number, for instance, it took some trial and error to find the right boots that wouldn’t be too slippery to dance in. In another number, the dancers portrayed nymph-like creatures, and had to wear a huge rubber pad on one shoulder, like a camel hump.

“We did a run-through and right away we saw that there was an issue,” Geary says. “It was just a mess, because we’d do backward rolls in them, and half of us would get stuck because the hump was so big.” After a couple more tries, director Sergio Trujillo decided the hump needed to go, and a much simpler costume was devised.

Paramour‘s Western number Andrew Atherton, Courtesy Geary

Mishaps Will Happen

Inevitably, things won’t always work out as planned, and costume mishaps can happen. The better you know the costume—but, more importantly, the better you know yourself as a dancer—the more prepared you’ll be.

Geary experienced this firsthand when he went on for the lead in VOLTA for the first time, and the character’s signature blue feather wig almost fell off. He’d felt confident enough after a run-through to clip in the wig himself, but during the performance he felt it coming loose. “I had never danced in a wig before, especially doing flips and stuff,” he says. “Then when I was flipping and dancing and doing pirouettes, I could feel it was hanging on by a strand of hair.”

What ultimately kept the wig on was Geary’s attention to his own movement quality. Normally a high-energy, explosive dancer, he realized this situation called for a slightly different approach. “I definitely knew my movement had to be a little more fluid, just to not do any quick, sharp movements, because then the wig would have fallen off,” he says. “You just have to adjust and listen to your body and what your costume’s doing in the moment. You have to make smart decisions without compromising the performance.”

Dunlap still remembers the advice an older dancer once gave him, that costumes almost have a life of their own. “I held on to that,” he says. “I think it takes away the feeling of ‘I have control, and if something goes wrong I’ve lost it,’ and makes it more about just responding to whatever happens.” In short, as Parks says, “It’s either work it or be worked.”