What It's Like to Be a Dancer in the Islamic Republic of Iran

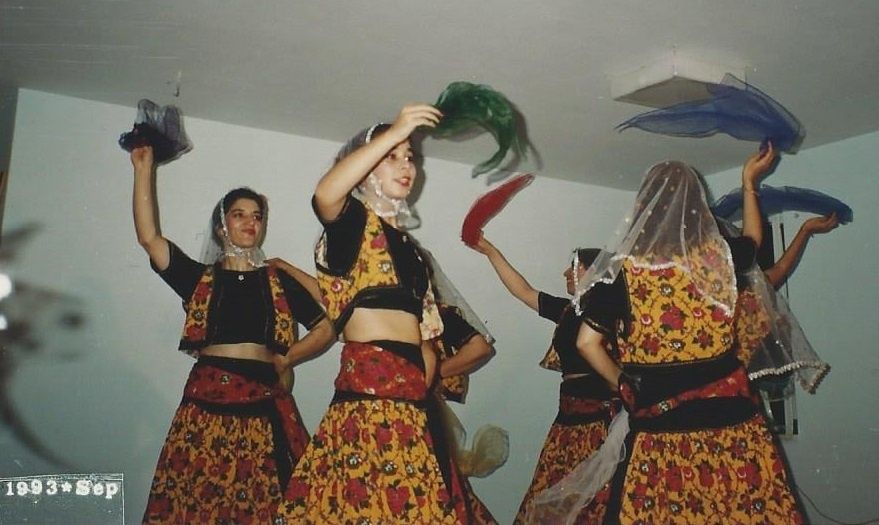

My underground dance classes in Iran began in 1990. The teacher was one of my mother’s friends, Nahid Kabiri, who had been in the Iranian Folkloric Dance Academy before it was dismantled in 1979 after the Islamic Revolution. Hidden from sight in the enclosed rooms of anyone who would allow us, she taught me and other women folk dances from the North, South and West of Iran, classical Persian dances, dances inspired by belly dancing and Azari folk dances.

Eventually, Kabiri established a performance troupe. Since we could be prosecuted for performing in public, she arranged her dark, damp and dusty basement into our performance space. A few women helped to clear the cobwebs and sweep the floors. Kabiri brought in old wooden benches that were joined together and covered by rugs to minimize cuts and scrapes from the rusty nails and wood splinters that jutted out of them. These rug-covered benches constituted our stage. She also borrowed what seemed to be over 100 rickety dining room chairs from her friends and neighbors to create the audience seating area.

Tickets were sold covertly to women only. The thinking was that if we were outed and the morality police raided the show, we could say that it was a gathering for women to celebrate the prophet Mohammed. At least, without men, the gravity of our crime would be greatly reduced. Our parents and family helped to spread the word to other trusted family members and friends.

Costumes were designed by Kabiri, sewn by a local seamstress and funded by all of us. For lighting, we had extra lamps installed into the fixture directly above the stage. We had one rehearsal on our makeshift stage on the day of the show. For fear of neighbors who may snitch, all attendees were asked to park or get out of their rides blocks away and walk to the basement door. Surprisingly, we sold out.

My memory is a little foggy from the night because I was so nervous. I remember our team-huddle in my teacher’s living room and her husband warning us about never referring to this performance in the future and the potential prosecutions that we might face as a result. They wanted to make sure that we had a single unified story in case of a raid.

One thing I do remember clearly was looking at the audience and seeing tears streaming down the faces. At the time, I did not understand why. But as I write these words, I understand the gravity, and the feeling of oppression and anger from seeing something beautiful hidden, quashed and forgotten.

An image taken of the underground performance

An image taken of the underground performance

Courtesy of the author

Iran has a long and complex history of dance.

In the Islamic Republic of Iran, dance is a crime punishable by fines, jail and even floggings. Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the repressive authoritarian rules set in place by the fundamentalist Islamic Republic and the view of the moving body as sinful and of female dancers as sexually provocative has ostracized dancers.

Even before the Islamic Revolution, it has long been considered an insult to be called a dancer (“raqqas”) or entertainer in Iran; these occupations are thought to bring shame to families. Travelers’ accounts and court records of professional dancers of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties, which ruled Iran from the 1500s until the early 1900s, show these dancers were part of the harem and performed for the amusement and pleasure of the reigning shah.

After the Constitutional Revolution of 1905, anything from the Qajar era or earlier was deemed to be corrupt and degenerate. Due to European influences, many Iranians experienced a form of cultural self-hatred and gravitated toward more “modern” Western cultures.

Professional dancers fell out of favor and became the available entertainment in nightclubs considered to be “low-class.” Over-sexualized dance performances in Iranian cinema between the 1950s and 1970s also reinforced this negative view of female dancers as immoral, fallen women who display their bodies, wear provocative clothing and perform seductive movements in front of men.

In 1979, the Islamic Republic banned any form of dance.

Despite the Qur’an’s silence on topics related to dance, music and visual arts, shortly after the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979 in Iran, Ayatollah Khomeini, the supreme leader, banished dance in any form, referring to it as frivolous. The Iranian classical ballet company, the national folk-dance ensemble and all forms of public dance were dismantled.

According to the regime, Islam regards the human body as a site of intense sexual emotions. Female dancers are thought to spark unlawful desire in men through movement and the exposure of their bodies. Therefore, fundamentalist laws in the Islamic Republic of Iran were passed, requiring all women to be veiled and not dance in public.

According to the work of Dr. Karin van Nieuwkerk, faculty of philosophy, theology, and religious studies in Radbound University in The Netherlands, women in Middle Eastern countries are often defined as sexual bodies; therefore, “moving is immoral for women since it draws even more attention to their shameful bodies.”

For dancers today, life in Iran is a perpetual duality.

Modern-day Iran comprises a multitude of cultural, linguistic and ethnic traditions. Many people who consider traditional folk dances charming and innocent and dancing at weddings to be a joyous activity may consider professional dancers to be corrupt and immoral. This hypocrisy and the stigma regarding the dancing body, particularly the female solo dancer, have resulted in the loss of much of Persian cultural expression.

There is also a large divide between attitudes toward dance in public versus private spaces, for men versus women and among civilians of metropolitan cities versus conservative towns. For me and many others, life in Iran can be described as living in perpetual duality: It requires observation of the regulations when outside, but simultaneously offers the ability to dance and have relative freedom within the privacy of one’s home.

This relative freedom requires keeping a low profile or paying hefty bribes due to the constant fear of the morality police, the pasdaran (Iranian Revolutionary Guards) or the basij militia (who receive their orders from the Revolutionary Guards and the Supreme Leader) who can break into homes to arrest and punish suspected offenders. There is the potential for beatings, torture, prison sentences and fines for dancing.

Like life in Iran, dance is also a dual concept. On one hand, it is thought to be disgraceful and shameful to move one’s body (especially in solo improvisations by women). On the other, it is a symbol of joy, celebration and unity.

There are four general categories of dance in Iran:

-

Folk dances

, including line dances (named after the village or tribe with which they are associated) -

Solo improvised dances

(delicate and graceful movements which are related to the Safavid and Qajar court dances that are generally danced in urban or private settings), -

Combat dances

(athletic motions which imitate combat and were once used to train warriors) performed in the Zoorkhaneh (roughly translated as “House of Strength”) -

Spiritual dances

(ritual dances of the Sufis or dervishes)

Classical ballet is regarded as an elite Western art form; therefore, in comparison to solo improvised dances, ballet is respected as a superior dance. In pre-revolutionary Iran, the government helped in creating national dance companies to perform theatricalized, sterilized and “respectable” versions (i.e., with minimal hip movement and loose-fitting costumes) of regional folk and solo dances within Western choreographic frameworks. They hired Western ballet choreographers, like former Royal Ballet dancer Robert de Warren, to teach and train these dance companies. This was thought to lend an air of seriousness and professionalism.

In an attempt to create a façade of cultural elevation, folk and solo dances were Westernized and irrevocably altered to mimic the movements of the invited colonizer. Due to this assimilation and appropriation, much of the history and tradition of folk dances may have been lost.

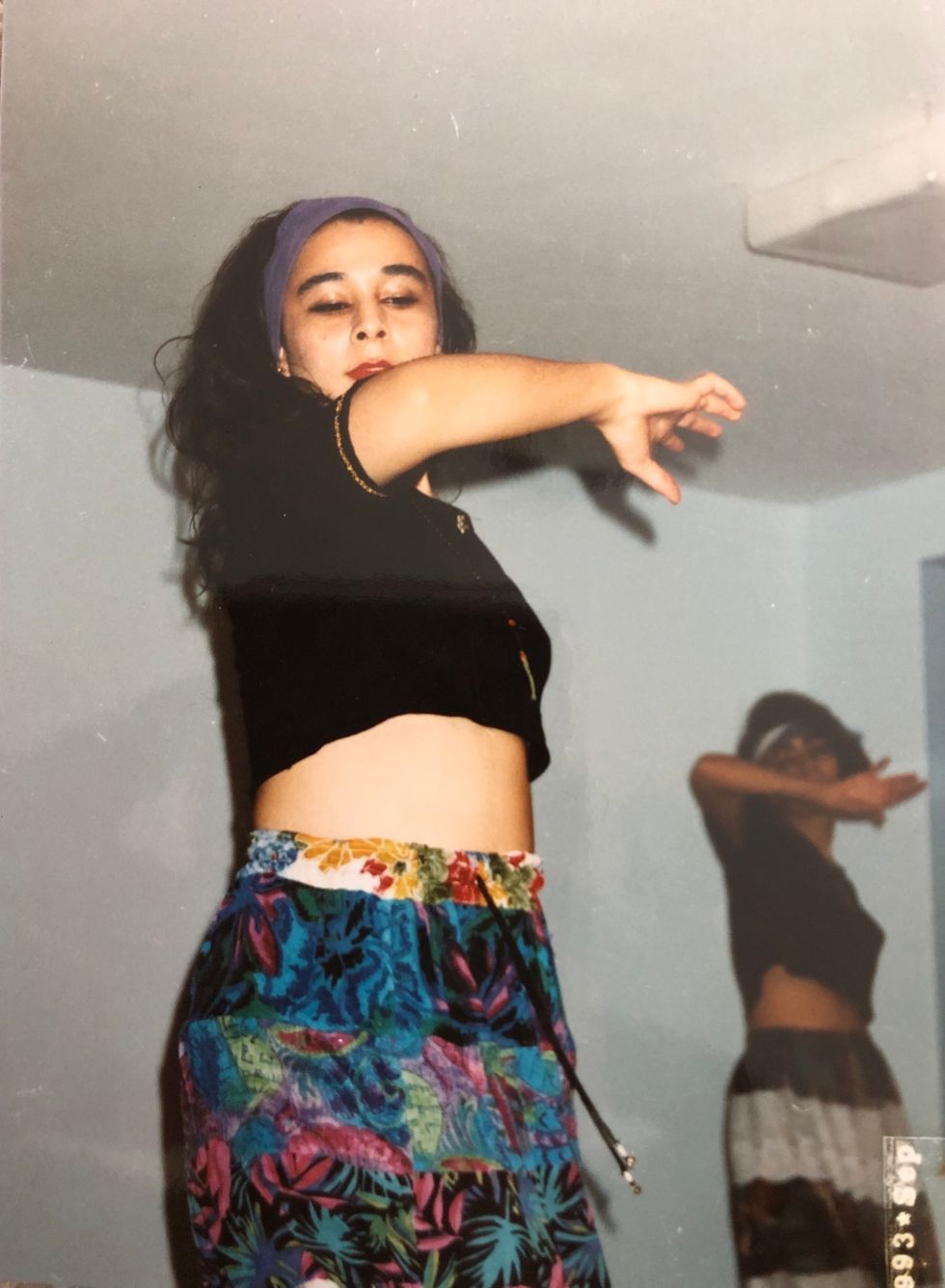

The author, performing in 1993

The author, performing in 1993

Courtesy the author

Being a dancer in Iran helped me discover my identity.

As a woman born and raised in Iran, I have experienced firsthand the government’s obsession with controlling and restricting the movement of the female body. I first started dancing in the early 1980s when I was 5 years old. My mother enrolled me and my sister in dance classes taught by a Persian classical dance teacher named Farzaneh Kaboli.

Years later I found out that she was, and still is, one of the most famous remaining dancers from pre-revolutionary Iran. She was one of the lead dancers in the Iranian National and Folkloric Dance Academy which had been directed by Robert De Warren for years. I studied dance with Kaboli for about two years before we moved to the US, and I began dancing with Kabiri, with whom I ended up performing, when we moved back to Iran several years later.

Initially, I started dancing because my mother signed me up. I continued dancing because it was one of the few things that kept me sane and hopeful in an atmosphere where I was once punished for wearing a backpack to school because it was a sign of Western influence. Dancing with friends and family at parties, dancing with my shadow in my bedroom, or dancing in a secretive performance helped me understand myself and discover my identity.

For so many years, I lived in an oppressive society where I did not have freedom of movement or speech. As I learned more about the dances from Iran and the Middle East, I realized how much the scholarly work has been dominated by Westerners (as you can see from the links in this story). These influences have resulted in positive and negative affects through preservation, alteration and appropriation.

Still, I dance because I want to feel in control of my body, I want to express my words through motion, I want to preserve dances from this region, I want to rid myself of the cultural self-hatred that I have been born into, and I want to educate others about the beauty and necessity of dances from this region.

Dance is a tool for resilience and political resistance.

Despite jail time, pledges to never dance again, hefty fines and physical threats, my first dance teacher, Farzaneh Kaboli, continues to dance, teach and perform. Her dance company has performed several times in theaters in Tehran for all-female audiences, offering a small glimmer of hope after decades of oppression.

The word jihad refers to an effort for self-improvement and a struggle against unjust oppression. For me and many dancers in the Middle East, dance is a tool for political resistance to oppressive regimes. Our jihad is the use of art as the weapon against unjust oppression from “Islamic” regimes and religious zealots.