What Eduardo Guerrero Learned From Choreographing For Other Flamenco Dancers

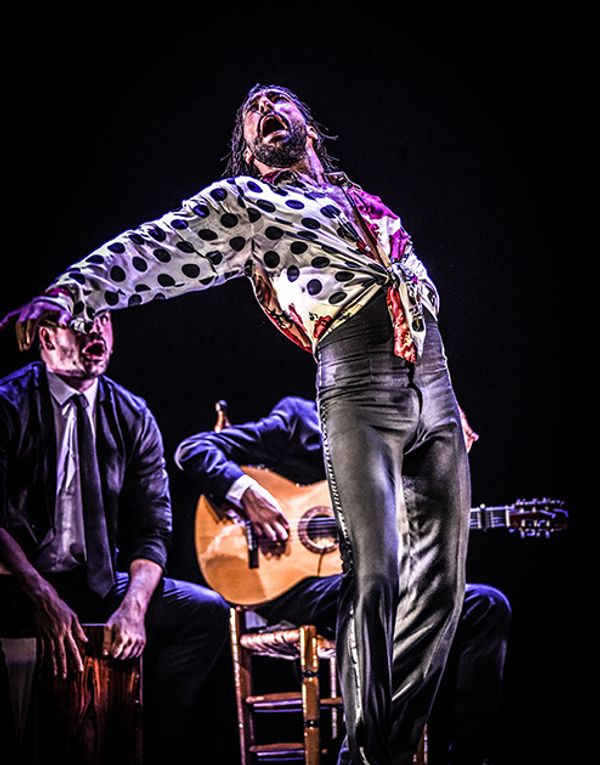

With a contemporary air that exalts—rather than obscures—flamenco tradition, and a technique and stamina that boggle the mind, Eduardo Guerrero’s professional trajectory has done nothing but skyrocket since being named one of Dance Magazine‘s “25 to Watch” earlier this year. His 2017 solo Guerrero has toured widely, and he has created premieres for the Jerez Festival (Faro) and the 2018 Seville Flamenco Biennial (Sombra Efímera). In the midst of his seemingly unstoppable ascension, he’s created Gaditanía, his first work utilizing a corps de ballet. Guerrero is currently touring the U.S. with this homage to Cadiz, the city of his birth.

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

Gaditanía is an homage to your hometown in southern Spain. How do you represent Cadiz in a work of dance that will be seen almost exclusively by an American audience?

When I sat down with Juan Jose Alba, the musical director, we decided that each piece of the show would be named after a street, a neighborhood or a square in Cadiz, so that we would feel obligated to visit each of these places, sit down in a corner and take notes on details—the ground, the smell, the sound—and develop a piece with the ambiance, color, rhythm and speed of the people on that street. It was our way of trying to bring Cadiz, the health and salt of its sea air, to a theatre in the United States.

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

You began your career working as a dancer in the company of other flamenco superstars like Eva Yerbabuena and Rocío Molina, but since starting your solo career, you’ve created pieces in which you are the only dancer. Why are you introducing other dancers into your work now?

I was really excited to get the chance to work with a corps, because I’ve never directed so many dancers before. I did it because these are the types of productions that you don’t get to see tour anymore. With the musicians, the dancers and the technicians, you’re talking about 13 or 14 people, and the cost is so high that it is not viable to maintain a company of that size. I remember my last tours with Eva Yerbabuena—when we were one of the few companies that maintained this large-scale format when touring abroad—and how we just kept cutting back the ensemble, until it was just two male dancers and one female dancer. It’s just what had to happen because maintaining anything larger is financially brutal.

How has the experience been different from working as a solo artist?

I began working with solo shows because I wanted to express myself. Now that I have tried working with a corps, I have a completely different take on how to envision a show, how to dialogue with other dancers, how they perform my steps. I get to see my choreography reflected on other artists, and they perform it differently. They’ve worked very hard because my style of dancing is totally different from the body language that they are used to.

What has been most difficult about working with a corps?

I am used to working on my own and spending as much time as I need in the studio, working at my own pace, on my own schedule, but I can’t subject other dancers to that. I really mistreat myself. I don’t mind spending 20 hours in the studio, but when you are working with other people, you have to be more accommodating, mainly so as not to exhaust the dancers before even beginning the tour.

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

Photo by Beatrix Mexi Molnar, Courtesy Columbia Artists Management

Why did you invite Maria Moreno and Jesus Fernandez—two fellow flamenco dancers from Cadiz and rising stars in their own right—to choreograph two pieces in the show?

I didn’t want this project to be all about me. Maria choreographed the alegrias, and Jesus created the zapateado. The rest is my direction and choreography, but I wanted to include other gaditanos [people from Cadiz]. And who better to choreograph a piece with a shawl and trained dress than Maria? And Jesus also has his own je ne se quoi.