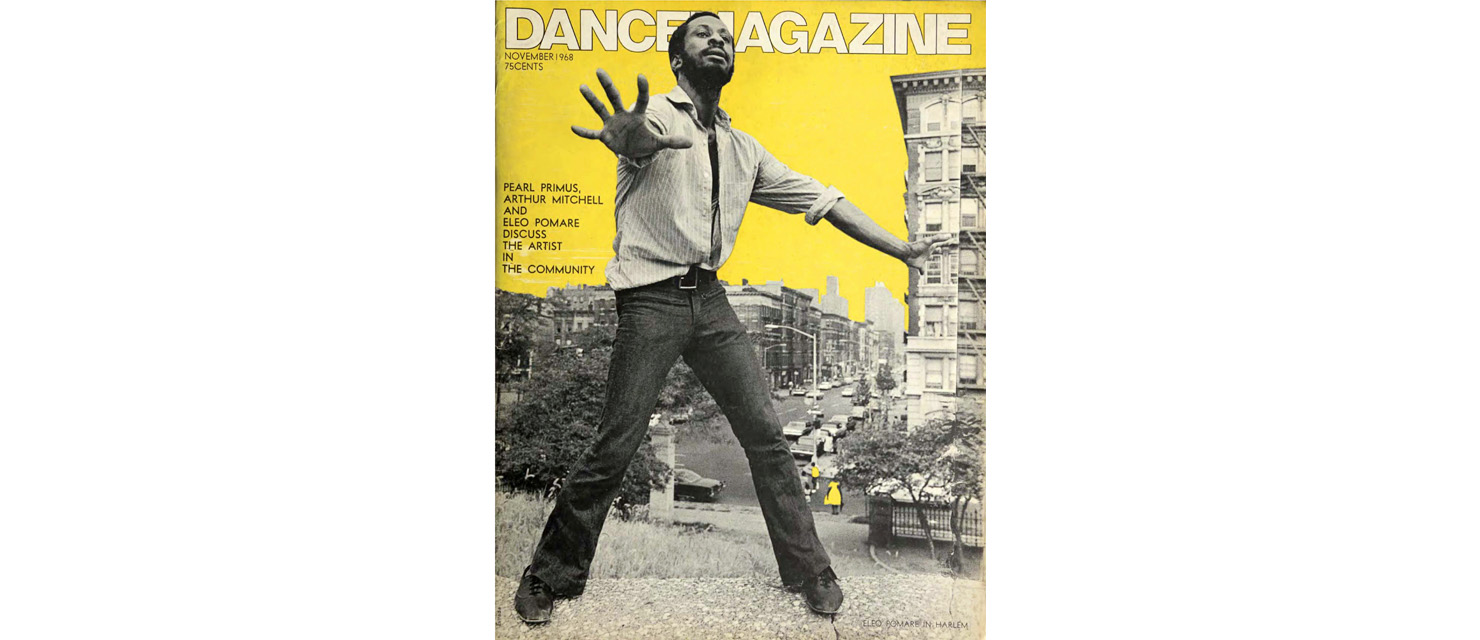

TBT: Eleo Pomare on Making Work for Black Audiences

In the November 1968 issue of Dance Magazine, journalist Ric Estrada profiled choreographer Eleo Pomare, 10 years after the then–31-year-old had established his eponymous company.

The Colombian American artist-activist had a knack for creating works that polarized critics, some of whom dismissively labeled his choreography, often about the Black experience, as too undisciplined and Pomare himself as an “angry” young man. “How many critics really understand the discipline it takes to erase all white influences,” Pomare wondered, “and yet dramatize precisely the world the black artist is struggling to escape from?”

Though his style and subject matter varied widely, as a choreographer he is perhaps best remembered for his pieces drawn from observations of urban America—like the controversial Blues for the Jungle (1966) or his signature solo Narcissus Rising (1968)—as well as 1967’s Las Desenamoradas, his haunting adaptation of Federico García Lorca’s play The House of Bernarda Alba. “I don’t create works to amuse white crowds,” he told Dance Magazine, “nor do I wish to show them how charming, strong, and folksy [Black] people are — as whites imagine them — [Black people] dancing in the manner of Jerome Robbins or Martha Graham. Instead I’m showing them the [Black] experience from inside: what it’s like to live in Harlem, to be hung-up and uptight and trapped and black and wanting to get out. And I’m saying it in a dance language that originates in Harlem itself. My audiences […] sense this and identify with it in a way no white man ever identifies with most white works.”

The recipient of a 1974 Guggenheim Fellowship and the first director of Harlem Cultural Council’s Dancemobile project, Pomare led his company, which toured widely in the U.S. and abroad, until his death in 2008.