This Is What It Felt Like to Be a Black Dancer Downtown in the 1960s

I came to New York City in August 1961 to rehearse Kicks and Co., the Broadway-bound musical that Donald McKayle and Walter Nicks had hired me to dance in. By 1962, I had moved into a studio at 51 West 19th Street, where, at last, I had space just big enough to dance in. It had been Paul Sanasardo’s loft, where he taught and rehearsed in the front space, while his dancing partner Donya Feuer lived in the rear. It was my fourth move, after subleasing a fifth-floor, cold-water flat on York Avenue and 74th Street with a toilet at the end of the hall shared by all the fifth-floor tenants, which Robert Powell had lent me while he was away; a spacious dumbbell-shaped sublease on West 72nd Street (over Bloom’s Bakery), which I shared with a tenor; another tub-in-the-kitchen tenement on East 4th Street, where the super liked to help himself to tenants’ belongings; and yet another second-floor sublet on Broome Street that had been Steve Paxton’s place.

Right after Sanasardo’s concert season at Hunter College that year, Feuer had gone to teach a two-week workshop in Stockholm. She never returned. And Sanasardo had found a larger studio right around the corner. So, I moved into Paul’s vacant third-floor studio on 19th Street, landing right in the heart of the downtown dance scene.

I spent my time teaching here and there, taking class and rehearsing. So, except for my obligatory scholarship classes at the Martha Graham School on East 63rd Street near First Avenue, my dance life comprised rehearsing with sundry downtown choreographers and taking as many classes as I could afford to catch up on my dance technique, including ballet classes at the Joffrey Ballet School on Sixth Avenue and 10th Street. Before moving to New York, I had been ostensibly studying architecture at MIT, taking a few classes at Boston Conservatory, teaching myself by watching movie musicals, and practicing stretches and turns.

Being enamored by the Cunningham technique, which I had tasted at the Dance Circle in Boston, I was fascinated by the possibilities that were percolating around me in New York, where John Cage, Philip Corner, Charlotte Moorman were redefining music, and Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Alex Hay and others were stretching the limits of painting. I was surrounded by the avant-garde. Then, to boot, Robert Dunn—husband of Cunningham dancer Judith Dunn—began teaching a course in new approaches to dance composition at the Cunningham studio on Sixth Avenue, at 14th Street.

Of course—encouraged by my friend and guardian angel David Vaughan—I took Dunn’s course, along with other dancers I already knew from Boston, like Ruth Emerson and Becky Arnold, and people I’d met in Merce’s classes, like Meredith Monk, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, Bill Dunas, Lucinda Childs and others. In 1962, a group of these dancers, spurred by Dunn’s inspiration, formed the Judson Dance Theater, presenting their experiments at Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square South, where something called the Judson Poets’ Theater organized by Reverend Al Carmines was already redefining theater performance.

Dunn devised simple exercises that generated pedestrian activity as activity, as dancing. One of my favorites was “Line Up and Pass Through.” I use that exercise to this day (with attribution) in my Dance Research classes.

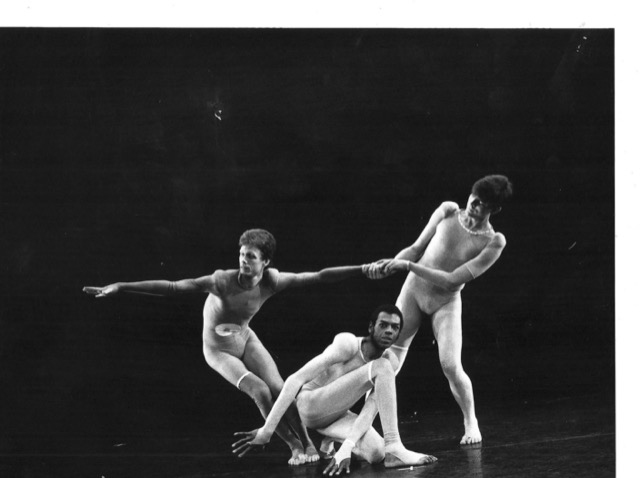

I was eager to perform for almost anyone who would challenge my precious dance technique—Donald McKayle, Merce Cunningham, Pearl Lang, Joyce Trisler—and did, but I was not willing to ditch technical dancing after working so hard to gain some measure of proficiency at it. I did a few Poets’ Theater shows, performing as one of three witches, alongside a singing one and an instrumental one, in Carmines’ version of Snow White. I also choreographed his musical Joan, which even had a short off-Broadway run.

I wasn’t much of a fan of Alvin Ailey’s work or that of most of the Black dancemakers I knew, with whom I felt no simpatico, since I had grown up in a largely white world and culture. Donald McKayle was the notable exception, especially since he had hired me from Boston and begun my professional dancing career. I kept busy making dances and dancing with friends and started my own company, The Solomons Company/Dance. I attended concerts by several members of the Judson group, including their epic first concert in 1962, which transformed them into a force, a legend in avant-garde dance. Although my company did perform at the Judson Church, it was not under the aegis of Judson Dance Theater.

I didn’t think twice about not being “invited” to join JDT, since I didn’t want to be constrained, as it were, by its aesthetic philosophy, as expressed later in the “No Manifesto.” I was still a fan of music and costumes and theater, albeit abstract. Then, in 1965, Merce Cunningham invited me to be the first Black man in his company—and the rest, as they say…

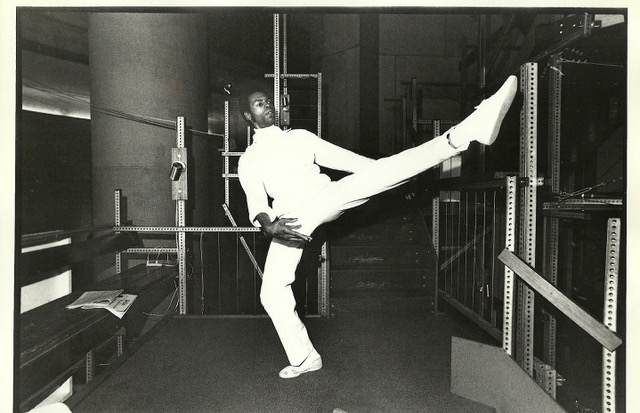

Gus Solomons jr performed with Pearl Lang, Donald McKayle, Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham and others, and founded The Solomons Company/Dance, as well as PARADIGM.