How Joshua Bergasse Won The Golden Ticket

He’s the Emmy-winning, Tony-nominated Joshua Bergasse in the playbill, but just “Josh Bergasse” (pronounced bare-GAHSS) when he affably introduces himself to the 70 people assembled at Broadway Dance Center for his advanced theater class.

They know who he is, of course, and it’s the reason they’re there. Reese Snow, BDC’s associate executive director, calls him “one of the finest theater teachers in New York.” He’s also the choreographer of the Broadway shows Gigi and On the Town (for which he won the Astaire Award and that Tony nomination), the off-Broadway hits Cagney and Sweet Charity, the NBC series “Smash,” and the new musical Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, opening this month at the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre.

Bergasse puts on Adele and starts a strenuous, fluid warm-up to prepare the class for the taxing but lyrical combinations they will dance to Sammy Davis Jr.’s swing-happy rendition of “The Goin’s Great,” from 1969. “A lot of my movement has fast directional changes, so I try to get their thighs and core really strong and warm,” he says.

Bergasse leading rehearsal. Photo by Jenny Anderson, Courtesy On The Town

As Bergasse begins the routine, it’s clear that he’s still, at 44, a beautiful dancer with a sleek line. You see how he landed three separate productions of West Side Story—often as a 5′ 5″ Baby John—and other musicals, some on Broadway, some not. Even back then, when not performing he was choreographing—summer theater, regional theater, Florida, Massachusetts.

He says he likes to tell aspiring choreographers about the years spent traipsing around the country, “because I don’t want them to think they’ve just got to get that show. Life isn’t necessarily winning ‘American Idol.’ Sometimes you just have to put the work in.”

Bergasse started putting the work in as a child, taking tap, jazz and ballet at Annette and Company School of Dance, in Farmington Hills, Michigan, outside Detroit. Annette is his mother, and by the time Bergasse was 15 or 16, he was teaching and choreographing recitals. “That’s when I got the bug,” he says. (Every so often, when he returns home, he teaches a class.)

His choreographic touchstones from the start were the movie musicals he watched “over and over, not realizing what I was learning—watching because I loved it. And now when I choreograph, that’s all a part of me.” His heroes: Michael Kidd, Hermes Pan, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire “and, of course, Bob Fosse.”

But when he choreographed the recent off-Broadway revival of Sweet Charity, he opted not to echo or redo Fosse’s choreography. “Before we opened,” he says, “I watched the movie, to make sure I hadn’t inadvertently done his choreography, because I’d seen it so many times.”

Sweet Charity. Photo by Monique Carbon, Courtesy Th Cooper Company

But when a step looked familiar, he discovered he’d “done it in a different number in a slightly different way.” It made him realize, he says, “how much these influences from that time were important to my development as a choreographer.” On the Town was less daunting, he says, because the Jerome Robbins choreography is not as well documented. And doing it gave him particular joy because, he says, “dance was a major part of the storytelling. It was written that way.”

Another influence was being a swing in Hairspray. Learning all of the tracks helped Bergasse “to understand the bigger picture of how the staging operates, how a big show functions.” That’s also where he first worked with Tony-winning director Jack O’Brien. O’Brien remembers him as bright, energetic, focused. “But I had no idea what his gifts were as a choreographer.”

Those became apparent, O’Brien says, when he saw On the Town. “It’s great fun to watch people growing and flowering,” which he did firsthand in 2014 for a Carnegie Hall benefit concert of Guys and Dolls. “Josh had no space, because the entire symphonic orchestra was onstage,” O’Brien recalls. He didn’t expect much from the huge “Luck Be a Lady” dance number, but it was “ravishing,” he says. “It had attack, it had masculine edge, it had danger, and it was done on the head of a pin.”

O’Brien is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory‘s director, and Bergasse surprised him again when they did a workshop in June. O’Brien expected three or four numbers, but “in three weeks he did everything. I mean capital EVERYTHING, exclamation point, close quote. It was not a sketch—it was a cornucopia of originality.”

The show is based on the 1964 Roald Dahl book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which became a 1971 movie musical starring Gene Wilder, Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, and a 2005 Tim Burton film with Johnny Depp. The stage version, with songs by Tony-winning Hairspray team Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman, direction by Sam Mendes and choreography by Billy Elliot‘s Peter Darling, opened in London in 2013, to mixed reviews.

The Broadway team has completely retooled it, Bergasse says. “We decided, Let’s go back to the book for this, let’s go back to the film, figuring which pieces of the puzzle are best for our version.” There’s also some new music, and, Bergasse says, “it has a different feel to it, very American. I think we have added a little more brightness and lightness.”

Bergasse says he’s usually drawn to a project by the collaborators and the story, and working alongside O’Brien was a dream come true. “Jack makes people feel they’re the most important person in the room. You feel safe to try things, you feel like you can do your best work.”

Without knowing it, he’s echoing what dancers say about him. Khori Petinaud, currently in Aladdin, did the Charlie workshop and worked on pre-production for Gigi. “He never made me feel like my input was not important,” she says. “He pushes, but he’s so friendly and warm. He jokes around.” She’s a regular at his classes, too, because, she says, “they are so extremely challenging.” She cites not only the “immense amount of steps in a small amount of time,” but also his musicality: “It’s not basic, and when you finally hit it in the right way, it’s so exciting.”

Gigi. Photo by Joan Marcus, courtesy Boneau/Bryan-Brown

“I like finding my material in the dancers,” Bergasse says. “Something indigenous to them. My philosophy is, ‘If it’s something I can do, then I’ve probably already done it.’ So let me find something new on you. Or let me help you create something.”

Like Petinaud, he enjoyed the sense of ownership when choreographers encouraged him to contribute to the process. “Not all dancers are good with that. They want steps: ‘Tell me what to do,’ five-six-seven-eight.” Bergasse looks for dancers “who will just do anything, just jump around inventing things.”

But there’s more to being a choreographer than jumping around. He devoted over a year to Charlie before rehearsals began, but only six weeks in the studio with dancers. “You never think, when you’re coming up, that you’re going to spend so much time in boardrooms,” he says. “You’ll be going from meeting to meeting to fitting. All the props and all the costumes have to be planned out before you start.”

With Charlie finally up and running, Bergasse will turn to musicals he says are “circling for a landing.” There’s Bull Durham, based on the 1988 baseball movie that starred Susan Sarandon and Kevin Costner; Smokey Joe’s Cafe, a revival of the 1995 hit created from the songs of Leiber and Stoller; and The Honeymooners, derived from Jackie Gleason’s classic ’50s sitcom about a Brooklyn bus driver.

Like his other credits, they’re a study in contrasting themes and styles—the frilly charm of Gigi was nowhere visible in On the Town, and the exuberant tap in Cagney made no appearance in Sweet Charity. “A jack-of-all-trades and master of none,” he jokes. More seriously, he adds, “I try not to get stuck doing one thing. I like to think of myself as a chameleon.”

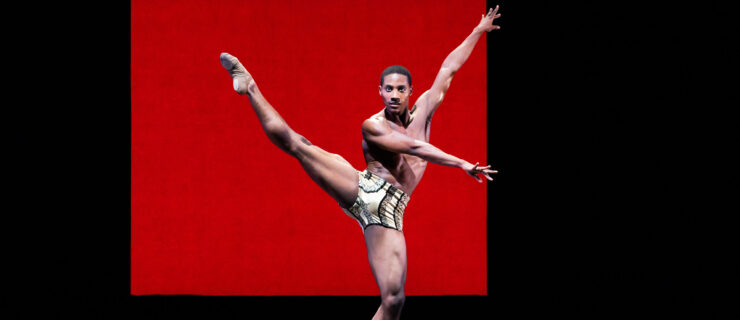

Cagney. Photo by Carol Rosegg, Courtesy Keith Sherman and Associates

He’s also developing a theater project “with a lot of dance” with his fiancée, New York City Ballet star Sara Mearns. At this point he can’t say much more than, “It will showcase Sara beautifully.” They’re hoping it will be ready in another year or so.

“She’s just so wonderful and so brilliant,” he says, “that sometimes it’s intimidating. But I can help her with certain things—certain theater things. And she helps me with certain things. I like to say she’s my choreography consultant. I’ll say, ‘I need you to look at this, because it’s not working—tell me how to fix it.’ She’ll look at it, and she’ll know like that.” At the final word, he snaps his fingers, adding, “She just lives and breathes all things movement.” Sometimes, he says, he lets her make the fix herself. When he’s in rehearsal, he says, they’d barely see each other if she didn’t come to the theater. “Sometimes she’ll sit through tech and sew her pointe shoes.”

He got to have some fun with pointe shoes in Charlie, in a satirical ballet for Veruca Salt. She’s one of four obnoxious children who compete with the hero, Charlie Bucket, to win a lifetime supply of chocolate from Willy Wonka. Another contender, Augustus Gloop, is Bavarian, and for his number, Bergasse researched cuckoo clocks and gave the dancers complex hand-slapping routines based on traditional Bavarian folk dances. He had to choreograph a pas de deux with no touching for Charlie’s mother and the ghost of his father—and a dance for his bed-ridden grandfather. He also collaborated with acclaimed puppeteer Basil Twist on choreography for Willy’s factory workers, the Oompa-Loompas. These are strange assignments for a choreographer, but Bergasse embraced them. “My favorite thing is to tell a story,” he says.