Nobody Has a Perfect Dance Body. How Can You Turn “Imperfections” Into Assets?

From the angles of your feet to the size of your head, it can sometimes seem like there is no part of a dancer’s body that is not under scrutiny. It’s easy to get obsessed when you are constantly in front of a mirror, trying to fit a mold.

Yet the traditional ideals seem to be exploding every day. “The days of carbon-copy dancers are over,” says BalletX dancer Caili Quan. “Only when you’re confident in your own body can you start truly working with what you have.”

While the striving may never end, there can be unexpected benefits to what you may think of as your “imperfections.”

Coppélia. Photo by Rosalie O’Connor, courtesy Boston Ballet.

Misa Kuranaga

Boston Ballet principal

The Challenge: After winning an apprenticeship to San Francisco Ballet at the Prix de Lausanne, Kuranaga realized she was still missing a vital part of her technique: turnout. “When I got to the States I hit the wall right away,” says Kuranaga. “I wasn’t cast and I was told I had to fix my foundation. I was already in my late teens and it felt like it was a little late.”

How She Tackled It: After she wasn’t rehired at SFB, Kuranaga enrolled at the School of American Ballet. Teachers like Suki Schorer and Susan Pilarre worked on rebuilding her technique, refining where and how she was using her rotation and building the strength to maintain it. “I needed a visual image to understand how to change, and Susie showed everything in pointe shoes every day in class,” Kuranaga says.

A Continuous Effort: The push to improve herself never ends: Kuranaga still sets goals in daily class. “I never skip class. If you take it seriously, it is an insurance policy for keeping your turnout and technique.”

An Unexpected Benefit: With an increased focus on the basics at SAB, not only did Kuranaga’s turnout get better, but her pointe work improved, too.

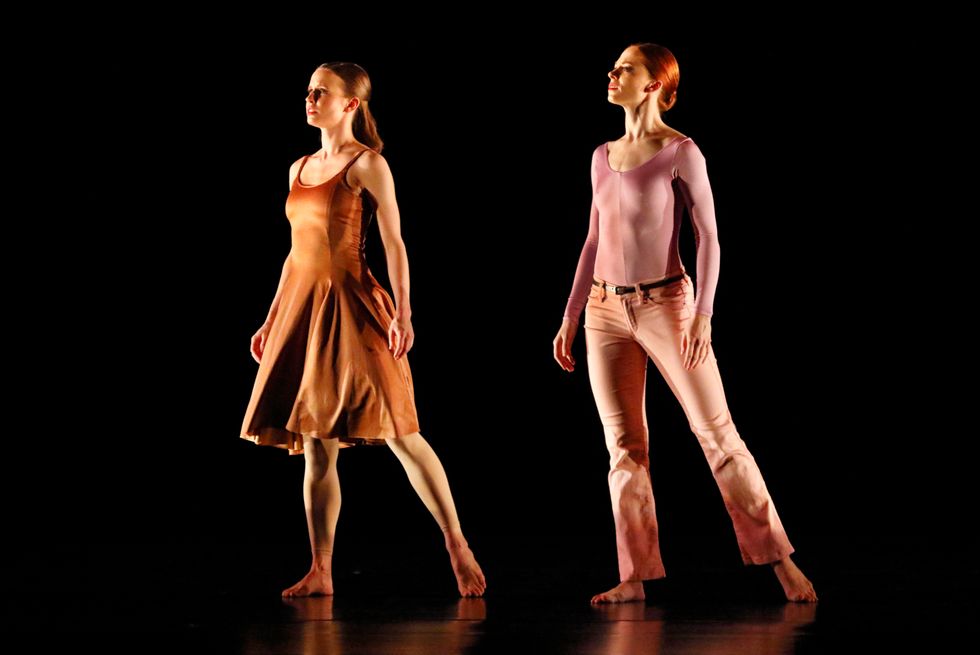

Kristin Draucker

Paul Taylor Dance Company member

The Challenge: Growing up, Draucker was self-conscious about her short calves. “Starting as a ballet dancer, most of the girls who were singled out as having ‘attractive legs’ always had a longer lower leg,” she says. Though gifted with a supple Achilles tendon, Draucker felt limited in her plié; it never looked stable or felt juicy to her.

How She Works It: “If I approach every plié like it is going to be awful, then it will be awful,” says Draucker. Instead, she works on phrasing the descent of her pliés, taking as much time as possible. “I use the music and try to make it look like I am always moving towards the bottom of my plié without tension.”

Cross-Training: Draucker does tons of calf-stretching to keep her lower leg muscles loose.

A New Mind-Set: “At some point I realized that really exciting work wasn’t about presenting your foot and leg for eight counts,” says Draucker. “Paul’s dances don’t have time for that; you can’t worry about all of those tiny things. He was creating new shapes on new people all the time, and while some things are hard for me, others are a better fit.”

Unexpected Benefits: “My hinge point is closer to the floor because of my shorter lower leg,” says Draucker. “Other people might have to think more about getting down to the floor, but for me, knee turns and other floor work come naturally.”

Courtney Henry

Richard Siegal/Ballet of Difference guest soloist

The Challenge: Six-foot-tall Henry stands almost 6′ 6″ on pointe. Although her first teacher encouraged her, complimenting her beautiful lines, Henry didn’t believe it. “Subconsciously, in ballet, I was always trying to blend and fit in, and I wasn’t able to recognize my length and my power,” says Henry. “I was moving like someone half my size.”

A Turning Point: Once Henry arrived at Alonzo King LINES Ballet, she realized her height was a gift. “Every-one was asked to be at their fullest capacity,” she says. She pushed herself to begin taking up more space and filling out her movement.

A New Mind-Set: No longer self-conscious about her height, Henry has come to love partnering. “When there is a good match, it is so nice to let go,” she says. “I have partnered with people half my size and I know now that it is not just about proportion, but also technique and momentum.”

Bonus: Strangers used to comment on Henry’s height all the time, but now they react differently. “People can see my height as an asset right away because I use it as an asset,” says Henry. “I am less apologetic and more comfortable.”

Caili Quan

BalletX company member

The Challenge: Quan has long struggled with her feet. “They’re where I always get corrections,” she says. “Everywhere I went they were a problem.” Quan grew up in Guam with spotty ballet training. Yet even after attending Ballet Academy East and later landing a contract at BalletX, her feet continued to be a challenge.

Confronting the issue: “In my mind, I thought I could fix my feet by just moving fast so no one would see them,” says Quan. But she eventually found that pushing herself to work slowly was what actually built strength.

How She Maximizes Her Line: Knowing she couldn’t change the structure of her feet, Quan decided to get to know every inch of them. She began wearing pointe shoes for every class—even when her rehearsal day does not call for them—focusing on how she can work her demi-pointe and transitions. And she is very particular about her pointe shoes. “I know everybody who works at the Freed store. I have tried everything,” says Quan. “I wear F maker, cut so low on the sides that I have to put water and rosin on my heels.”

A New Mind-Set:

“Some ballet dancers don’t have great feet, but the way they use them is magical,” says Quan. “For me it is not about the end point, but showing off the in-betweens. How you get there can change the look of how you dance.”

Jeffrey Cirio

English National Ballet lead principal

The Challenge: Cirio, 5′ 9″, always knew he would be on the smaller side. “But I was a huge fan of Fernando Bujones,” he says. “He danced with amazing ballerinas and wasn’t very tall either.”

How He Became a Prince: Naturally a quick mover, Cirio could have easily spent his career dancing soloist roles or being pegged as the “contemporary guy.” But he realized early on that there were both physical and mental components to dancing bigger and commanding the adagio solos he coveted. “Practicing transitions, paying attention to your tombé pas de bourrée as much as the turn and the preps into jumps can make you look elegant and lengthened,” says Cirio. “Dancing big is a mental game, and you have to project confidence and know how to push your body.”

The Importance of The Right Director: Cirio says he owes a lot to his first artistic director, Mikko Nissinen of Boston Ballet. “He never pigeonholed me. He gave me the chance to do prince roles and, in effect, dance up. In another company, I might not have been able to dance Balanchine’s ‘Diamonds.’ ”

Making It Work:

In preparation for his first full-length featured role, in Nureyev’s Don Quixote, a ballet master taught Cirio how to cross-train with body-weight exercises, cardio and band work (with a lot of reps). “You never know who your partner will be, and you have to be prepared to partner the person in front of you. You might have to relevé to be able to do that finger turn.”