Op-Ed: Is Ballet "Brown Bagging" It?

Janet Collins, Raven Wilkinson, Debra Austin, Nora Kimball, Misty Copeland, Francesca Hayward. All of these successful black ballet dancers have something in common: they skew toward the fairer end of the sepia spectrum.

Onstage, the duskiness of their complexions can be all but washed out, bleached by the lights. From the audience, they could present as a white girl back from a beachside vacation, or be perceived as Latina.

This observation is in no way meant to challenge these women’s “blackness,” or their talent. It’s to highlight a long-overlooked fact that, historically, artistic directors have shown a predilection towards black ballerinas with lighter skin tones.

Misty Copeland in Swan Lake. Photo by Gene Schiavone, courtesy ABT

This reality is not only the case in “white” ballet companies, as the same could be said of Dance Theatre of Harlem. Even for a company that is an oasis for dancers of color, beauty politics have always been in play. In its heyday, most of the women who were pushed and promoted—like Lydia Abarca, Stephanie Dabney, Virginia Johnson, Judy Tyrus, Christina Johnson, Tai Jimenez, Kellye Gordon-Saunders and Alicia Graf—shared the trait.

So the question is:

Is ballet “brown bagging” it?

The brown paper bag test was a type of racial discrimination used to determine whether someone could have certain privileges. Only those whose skin color was the same shade or lighter than a brown paper bag were allowed into certain schools, churches and nightclubs.

Those who were light enough could pass for white and collect all the privileges that went with it. For instance, Raven Wilkinson‘s complexion allowed her blackness to go “undetected,” which enabled her to dance with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo.

Internationally, the conversation about ballet’s lack of black dancers is cresting. Artistic heads are just beginning to engage, and realizing how complicated the issue is. But the subtle nuances have yet to be broached. And the silent color barrier is one of them is.

To white people, one brown body might seem the same as the next, and idea of bandying about “shade” seems trivial. However, within communities of color, it is a running issue as melanin levels have systematically been used to categorize and divide us.

Light-skinned privilege is a historical throwback to the days of slavery where skin tone could determine your quality of life. Color was used in the assignation of labor and privileges for slaves (lighter in the house, darker in the field). It could dictate levels of access, acceptance and treatment.

Sadly, as is often the case with the oppressed, as a community African Americans have adopted this mentality. We’ve created our own internal caste system where more value is placed upon those who are lighter. We still live out our scars. “The Color Line” like the melanin that produces it runs deep…

Even today, black people are accustomed to our “public representatives” in entertainment, business and broadcasting looking less than toasty, especially the women. Seldom would we comment upon it publicly or in mixed company, for fear of being accused of tearing another down or being labeled a “hater.”

But privately amongst ourselves, upon hearing about black person rising to a position, it is common practice to ask on the sly, “Well, is she black black?” It’s almost never about the actual person, but about the system that holds us all under its thumb.

Because we know that just like white skin, light skin has its privileges. (The “you have to be twice as good to get half as much” mantra handed down to most black children hits doubly hard for the melanin strong.)

That is not to say that there aren’t darker-skinned women who are highly successful. It feels like a communal high five ripples like a wave at a baseball game when a darker-skinned woman ascends in any field; we celebrate “and she’s chocolate.”

However, you have to wonder, how many more were denied access because they were too dark? We will never know, just as we might never know the talented ballerinas thwarted and redirected towards the modern or commercial dance.

This is a difficult reality to write down in black and white. As I do, I fear that I am outing a very private, intimate vulnerability in my community. But if it is my hope to transform these conversations, then I myself must take the risk. If we are authentically working to create sustainable change, to move towards real integration, then we must talk about the really hard really real stuff. (Breath….)

The English National Ballet corps. Photo by Alastair Muir, courtesy ENB

There has been much ado about the concept of “breaking the line” of the corps de ballet with brown bodies, which are argued to distract from the uniformity of the corps in works like Swan Lake and Giselle. Often, for such ballets, white dancers are asked to “whiten” themselves even further. Hence, the browner the body, the bigger the break. It stands to reason that light-brown ballerinas would be aesthetically preferable.

The function of the classical corps de ballet explains why black men do not fall prey to the color barrier: Men never stand in lines as swans, wilis or sylphs, so the depth of their brownness is never an issue in regards to the aesthetic of “classicism.”

In fact, where males are concerned, it seems the blacker the berry the sweeter the pas de deux. It is an ironic twist that the opposite color code exists for the men: Top male dancers like Arthur Mitchell, Mel Tomlinson, Ronald Perry, Carld Jonassaint, Carlos Acosta, Eric Underwood and Brooklyn Mack have been unmistakably black.

In 1957, Balanchine’s Agon shocked people when he cast a black man (Arthur Mitchell) in a pas de deux with a white woman (Diana Adams). The general public was outraged at the black and white bodies intertwining in the sexually suggestive choreography.

While breaking a cardinal taboo (and possibly a few laws in some states) it shattered a barrier. Though people were not pleased, once presented, that bell could not been un-rung, the images could not be unseen. Agon opened the door for the black male body to inhabit the ballet space.

However, another reason why the black male body is more acceptable is rooted in very function of the male ballet dancer itself. His role has always been in service to his ballerina. Since the white eye is accustomed to seeing the black male body in that station, it fits the stereotype of the black subservient laborer (he hauls, lifts, supports, fawns). While being in service, this role simultaneously evokes the Mandingo trope of the hypersexual black male, placing him in dangerous proximity of the unattainable white woman he undoubtably desires. This intimacy creates fear, anger and titillation in white eyes allowing them to be both outraged and turned on. Granted, these statements were more overtly obvious in 1957 when Balanchine was creating Agon and Jim Crow was still in full swing (two years before 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered for allegedly “flirting” with a white woman). However, even in 2017, we still maintain the residual film of these stereotypes.

Meanwhile, the black female ballerina is saddled with her own stereotypes. The “ballerina” represents the unattainable ideal of woman: the chaste, fragile beauty, the ethereal object of desire. In short, she is the antithesis of blackness.

Where the white female body has always been presented as the epitome of beauty, the black female body is burdened with the trope of the hypersexual Jezebel slut, the work mule, the caretaker servant to her Mistress and the bossy, overbearing castrator to her Mister. She is sweaty, tired, angry and inelegant. Imagine Nina Simone’s Aunt Sarah—skin black, arms long, hair wooly, back strong enough to take the pain inflicted again and again—in a tutu, or the characters of an Ernie Barnes painting as a corps de ballet.

If a ballerina must be black, best that she doesn’t look it. Lighten her up to the point where her blackness barely registers, or at best she can…pass.

I do not believe that artistic directors are fully cognizant of these antebellum leanings. I doubt that this generation of directors even knows what the brown bag test is. This tendency is a product of societal programing that we are all participating in by default. It is how our eyes have been trained to see, because our concepts of beauty are not always our own (remember that Meryl Streep monologue about Cerulean blue from the Devil Wears Prada?).

The rise of Lauren Anderson to the rank of principal dancer at Houston Ballet in 1990 marked her as not only the first black female to be promoted through the ranks of a major (white) ballet company, but the first who was undeniably black. Artistic director Ben Stevenson received hateful letters daily for his decision to exhibit her talent.

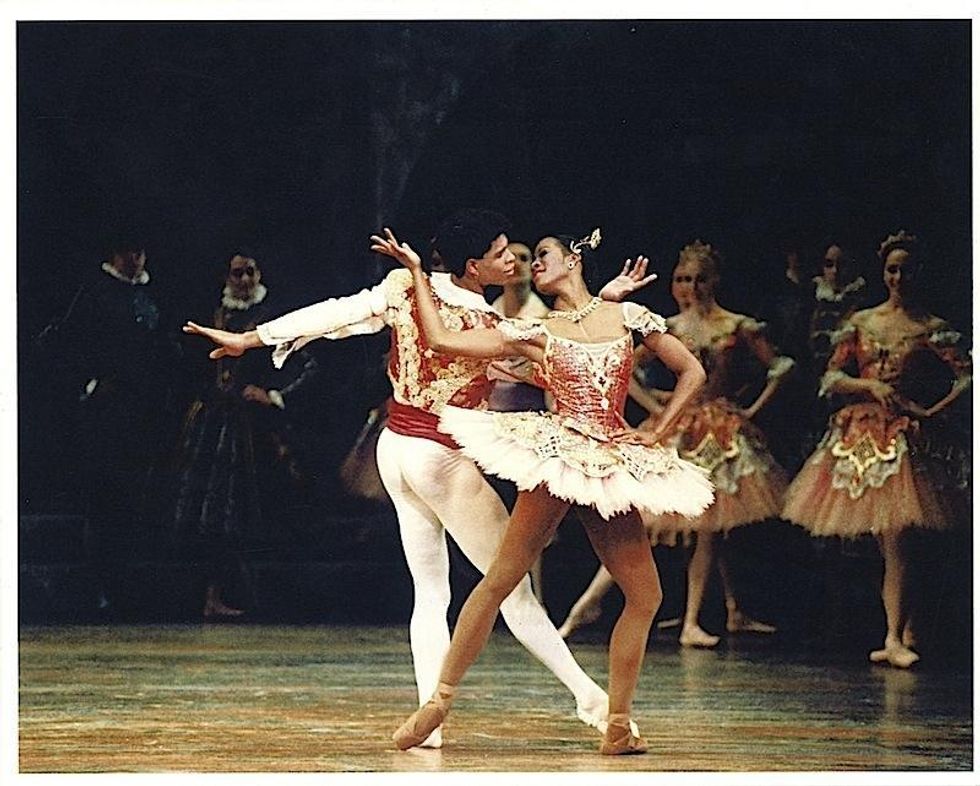

Lauren Anderson with Carlos Acosta in Houston Ballet’s Don Quixote

While Anderson was making her mark, Andrea Long-Naidu and Robyn Gardenhire were literally the “black swans” in the corps at NYCB and ABT, respectively. Through the 80s and 90s, DTH was producing generations of “brown” and “dark” principals and soloists: Yvonne Hall, Karen Brown, Cassandra Phifer, Charmaine Hunter, Lisa Attles, Bethania Gomes and Paunika Jones. For these women, their journeys were been long and arduous, working twice as hard to get just enough.

The good news is that there might be a shift on the horizon. Presently, there are young chocolate ballerinas climbing the ballet tiers around the world: soloist Michaela DePrince at Dutch National Ballet, Precious Adams with English National Ballet, Ashley Murphy with The Washington Ballet and Jenelle Figgins with Aspen Santa Fe Ballet would all fail the brown bag test.

Michaela DePrince in rehearsal. Photo by Altin Kaftira, courtesy DNB

With higher visibility, their images will not only inspire browner-skinned students to pursue ballet, but also encourage dance educators to not be so quick to eschew them into a modern track because they fear there is not a place for them in the ballet world.

With ballet organizations getting more serious about training dancers of color, we should see more shades coming through what is referred to as the “pipeline.” But will there be as strong of a commitment to hiring them into professional companies? It’s all a waiting game.

This is not to shame the light-skinned dancers or even directors who up until now might not have been aware that this secondary color line existed. But as we work to create equity, we must confront and question our recessive biases, then ask ourselves, “Do they have a place here?”

In the phantasmagorical world of ballet where swans come to life, and dead women dance en mass, these characters are neither human nor real. They can look like anything, be any color the imagination can conjure. So then why not a darker shade of brown?