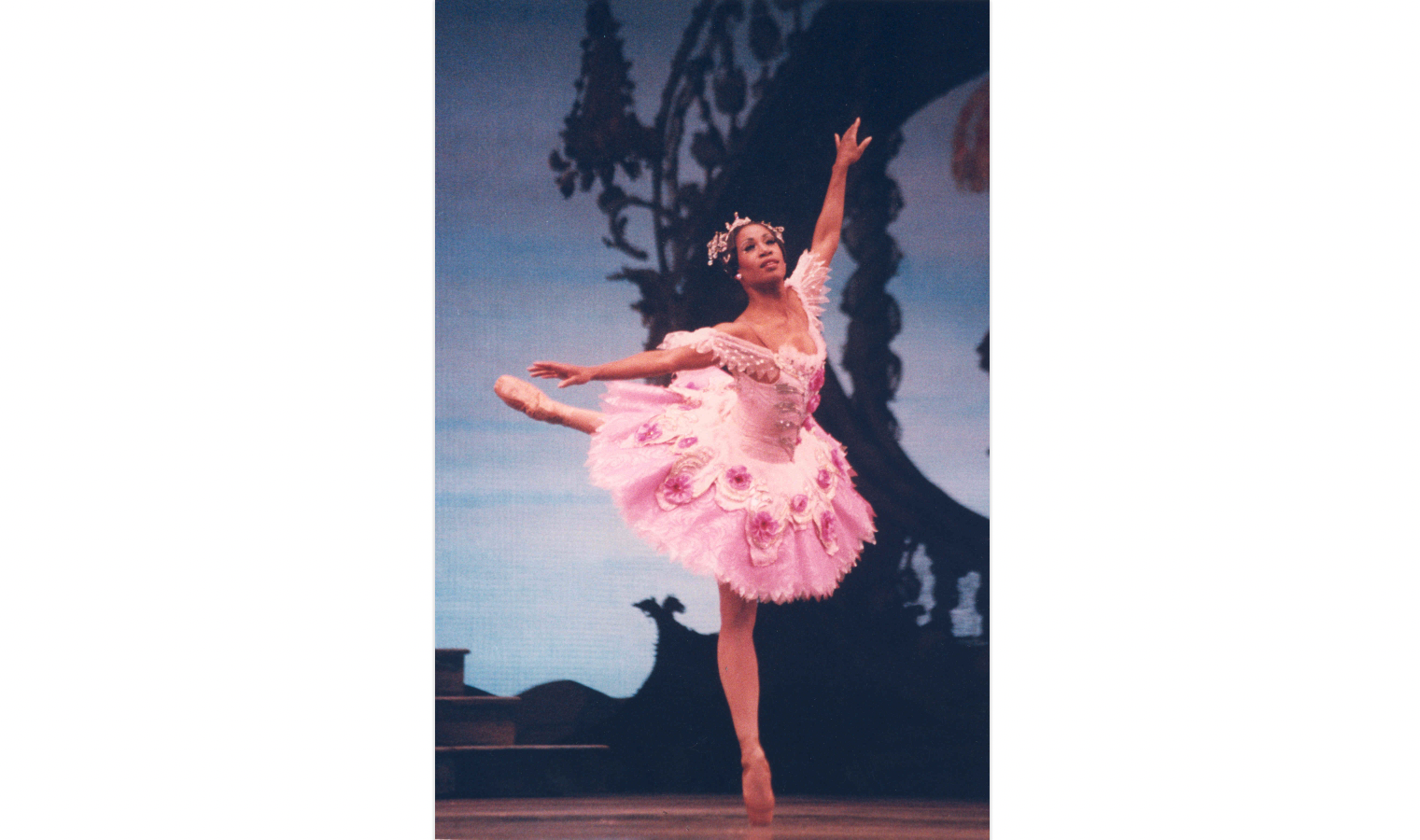

The Iconic Lauren Anderson’s Life Story Onstage

Three years ago, Lauren Anderson was contemplating writing her autobiography when acclaimed slam poet Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton contacted her about working on a dance-theater piece about her life. The result, Plumshuga: The Rise of Lauren Anderson, written by Mouton and with choreography by Houston Ballet artistic director Stanton Welch and Harrison Guy, premieres this month at Stages in Houston. The production features DeQuina Moore as the narrator (“Poet Lauren”), performances by Houston Ballet dancers and original music by Jasmine Barnes. Plumshuga chronicles Anderson’s dramatic rise as the company’s first Black principal, her struggles with addiction and her road to recovery. Anderson speaks to the experience of telling her story, and eventually sitting in a theater seat to watch it.

People would hear my narrative and say, “You should write a book.” I have read every book by every ballerina and I have lived the life. I thought I should wait a bit to tell my story because I knew that I would have to tell the truth. So I had been putting it off. I met this wonderful woman, Tamara Washington, who is my manager now. She wanted to get a timeline and plan together. I wondered, Who am I going to trust with my story? I started to request the recordings from all my interviews. I figured I would put them together and make a book.

And then I got an email from poet Deborah D.E.E.P. Mouton. She had done a spoken-word piece with Houston Ballet after Hurricane Harvey, so I knew her work. She wanted to have a meeting with me. I assumed that she wanted to pick my brain about an education project, so I said sure.

When she told me that she wanted to write a theater piece based on my life, I literally shrank down in my chair to make myself as small as possible. “You want to write about me?” It wasn’t what I was expecting. Why? My usual ballet story is so boring, because I had not told anyone the real story—which includes my struggle with addiction and eventual recovery—especially to someone not in the recovery community.

In the beginning, Deborah was so respectful of my time. I told her about my childhood, we talked about surface-y things—I am good at telling a story. What was interesting is that she asked me how I felt, not just what happened. That brought me closer to her. I started thinking, Wow, she really wants to know my story. When the media asks me about my life, they want juice, they don’t care how I really feel. They want to focus on fame.

After a year and a half of interviews, I felt like we could go deeper. We met sometimes twice a week. This was around the time that George Floyd died, so it was a charged time, and my emotions were right at the surface. I was being asked to speak on a lot of panels about how we feel as Black dancers. Then I got tired of talking about that. “I am not here to tell you how you should feel. Your feelings are legitimate.” After saying that so many times, it started to work on me.

I am not a choreographer. I can re-create a production, but I don’t have that gene. Deborah, though, is a choreographer of words. As we spoke, I kept seeing idea bubbles exploding over her head. One of the most flattering things she said to me was that I made things easy for her. Because I am descriptive, and that’s because I am an actress, a dancer and a performer. I have to have that running dialogue in my head to make an audience believe what I am doing. She turned my words into a full-blown dance-theater piece. When she handed me what she had written, it was like a road map of my life, including exact moments from my childhood. Young Lauren enters and turns around, plays with a ball, flips over the handlebars of a bike. There were dancers coming on- and offstage. She literally had written out her total vision with complete stage directions, even some lighting cues. I just thought, Wow, this is spectacular.

After a second reading, we corrected a couple things, switched some timing around, little bitty things. She wanted it to be accurate and authentic, so she sifted through every word. She had this desperation to get it right. At some point, I had to let the script go because it’s her theater piece. But she got it right. One scene even portrays a time when Carlos Acosta and I went salsa dancing, and it absolutely changed our partnership onstage. I had to relinquish control to him, which had been uncomfortable to me until that night out with him!

The story is told through the lens of recovery because that is where I am right now.

If you’d asked me to do this 20 years ago, it would have had a different flavor. But I am 57 now, and recovery has given me a solution-oriented point of view. I don’t think there are problems, just solutions. If I was still in addiction, I would have to leave all this stuff out and only tell one part of the story: my dance life. But in Plumgshuga, addiction and abuse are shown strongly through dance and, of course, spoken about. I was coping with all kinds of pressure, not necessarily success—because I never really felt successful, and that was part of the problem, not liking myself. At first it was just fun, but then I drank and did drugs to feel better about a lot of things, to forget about some things and to not care about others. I know that sharing this will help other people.

I can tell you that when I watched the performance workshop, it was devastating. It was beautiful and wonderful, but at the end I was emotionally exhausted. I was so proud, proud of the piece, proud of myself because I know what I went through. I was amazed with Deborah, and Stanton Welch and Harrison Guy for their choreography, and so honored knowing what everyone poured into it.

Afterwards, I sat on a panel in front of a group of people who’d watched the most amazing parts of my life and the jankiest parts of my life, and felt all the feels. Then came a barrage of compliments that I could not handle. I turned to Stanton and said, “I don’t know how to do this.” Then I told Deborah that I needed to go back to therapy to learn how to say “thank you.” It was interesting because usually I love applause. Plumshuga makes me feel everything, and that’s a lot. Oh, about that book, Deborah will be writing it.