Lauren Lovette Isn't Afraid To Send Shock Waves Through The Ballet World

Not all ballet dancers cling to their youth. At 26, Lauren Lovette, the New York City Ballet principal, has surpassed the quarter-century mark. And she’s relieved.

“I’ve never felt young,” she says. “I can’t wait until I’m 30. Every woman I’ve ever talked to says that at 30 you just don’t care. You’re free. Maybe I’ll start early?”

She laughs—a frequent sound when spending two minutes or two hours with Lovette. The epitome of sparkling youth, both in person and onstage, she isn’t someone that the mind naturally lands on when considering old souls.

But the thoughtful, introspective dancer, who also loves to draw and cook, is banking that with age comes some clarity. At the moment, she’s learning how to say no. “I never really had to do that before,” she says, “because I didn’t have this much on my plate.”

Lovette is learning when to say “no.” Photo by Erin Baiano, courtesy NYCB

Along with her dancing life, Lovette has briskly forged a choreographic career: In the course of a little more than a year, she has created two works for NYCB—most recently, Not Our Fate—as well as the delightful program closer Le Jeune, for the ABT Studio Company. Part of the group’s current tour, it will be shown at the Ailey Citigroup Theater in April.

“She has a quickness, a brightness to her work and a fleetingness to her steps,” says Kate Lydon, the Studio Company’s artistic director. And if members of the group, as many do, eventually join American Ballet Theatre, where Alexei Ratmansky is artist in residence, they need speed.

“He is fast,” she continues. “I thought that her sensibility would match well with the development of the dancers.”

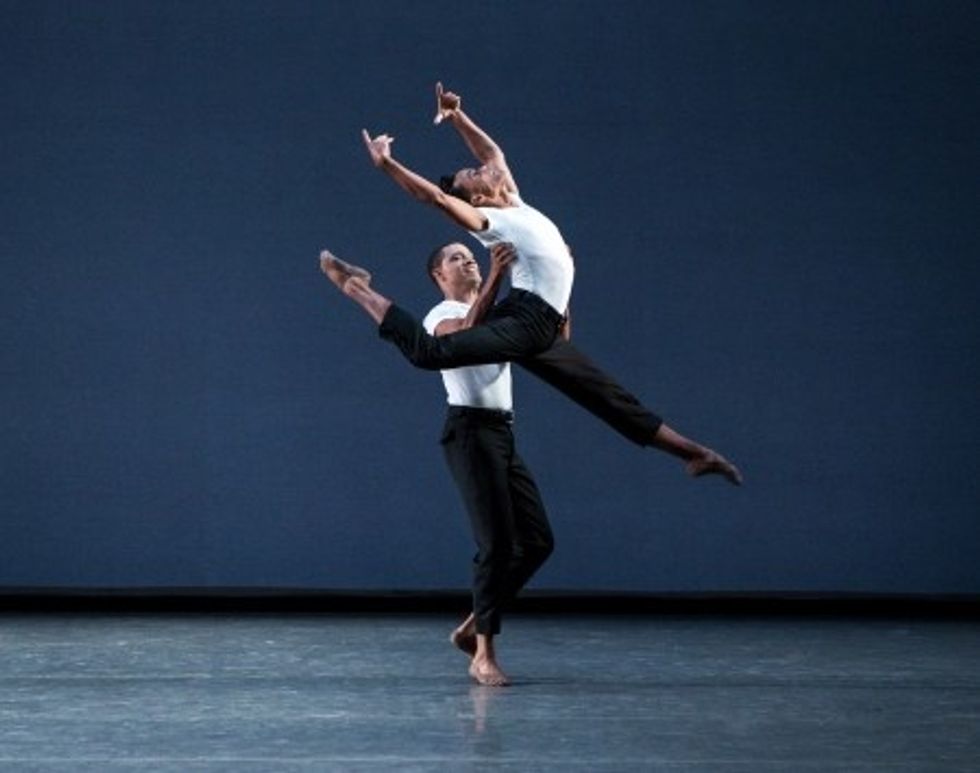

But it was Not Our Fate that placed Lovette at the forefront of the recent debate about same-sex duets that was instigated by a Facebook post by Ratmansky. It featured a Photoshopped image of a woman lifting a man; Ratmansky’s entry starts with: “sorry, there is no such thing as equality in ballet.”

Not Our Fate

features a romantic pas de deux for Preston Chamblee and Taylor Stanley, and on opening night the sight of them dancing together sent a shock wave—the good kind—throughout the David H. Koch Theater.

“I was immediately touched by her vision for the piece,” Stanley says. “It was how I’ve grown up and struggled with my sexuality, and how I’ve come to accept myself in the end. She said I was this person who was constantly in search of love or someone to give me comfort and make me happy, but that there is rejection each time. So there’s this push and pull of ‘Do I continue to go for this, or do I retreat and not fully be who I want to be?’ I was like, ‘Oh, just what I was writing in my journal this morning!’ ” he says.

But this wasn’t Lovette’s first attempt at same-sex partnering. Last summer at the Vail Dance Festival, she choreographed a romantic pas de deux for Patricia Delgado and herself featuring spoken word by the genderqueer poet Andrea Gibson. “I feel like we fell in love with each other onstage,” Lovette says. “I loved that show.”

And she’s proud to be a part of the gender conversation. “A lot of times, we talk about things but we don’t actually do them,” Lovette says. “We’ll post on social media, but when you actually make art that represents what you’re trying to say, you’re a part of the action.”

And for Lovette, being part of the action doesn’t stop offstage. As a Puma ambassador, she is developing a variety of educational outreach programs. “It’s not just about having a dancer come in and teach a class and be like, ‘I’m inspiring!’ and then leave,” she says. “It’s putting in a new floor, a new barre. Kids don’t have good floors.”

She’s also passionate about the Black Lives Matter movement; Not Our Fate includes a moment with the African-American dancer Christopher Grant that references racial injustice. “It’s not our fate,” she explains, “to hate all these people that are different than us.”

Preston Chamblee and Taylor Stanley in Lovette’s Not Our Fate. Photo by Paul Kolnik, courtesy NYCB

Lovette is trying to figure out, as she puts it, “how to weave the basket of my life.” In the future, she hopes to collaborate with more artists outside of the ballet world, like Jon Boogz, the movement artist who created the “Color of Reality” short film with visual artist Alexa Meade and jooker Lil Buck, who is one of Lovette’s close friends. Jon Batiste, the jazz musician and bandleader of “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” has also expressed interest in working with her.

“I can’t do everything, so I’m trying to figure out what causes mean the most to me,” Lovette explains. “What do I really want to say?”

Lovette’s nimble choreography, like her dancing, is lushly emotional yet not mannered. Indiana Woodward, the NYCB soloist featured in Lovette’s 2016 ballet For Clara, says, “The steps flow out of her like a giant waterfall of choreography.”

Lauren Lovette choreographing in the studio. Photo by Erin Baiano, courtesy NYCB

For Lovette, it’s a form of expression, which is what drew her to dance in the first place. “It was the way that I could say everything that I wanted to say without really saying it,” she explains. “I have a greater platform to do that through choreography. It’s kind of like inflection: If you’re relating words with dance, dance would be how you say the word, but the choreography is the actual sentence. Now, I get to actually form the sentence.”

And that, for anyone in ballet, but particularly for a woman, is empowering. Yet as one of the few female choreographers working in ballet, she feels some pressure. “How can you not?” she asks. However, she can’t wait until it’s not a question. “I can’t wait until it’s normal.”

She recognizes that being a woman was what helped her get the opportunity to choreograph in the first place. “I’m going to take it as a positive thing,” she says. “Maybe I got my first chance because they needed a female choreographer. Who cares? I’m really happy that it happened.”

Lovette wasn’t randomly chosen, however; she had already shown promise at the School of American Ballet when she took part in its Student Choreography Workshop. Then, as now, she was able to draw out her dancers’ best qualities. Woodward, a close friend, believes that Lovette’s sensitive nature is what allows her to read different energies in the room.

“I feel strongly about uncovering how people want to dance,” Lovette says. “They show you all the time—you just have to be observant. Taylor Stanley can do anything, but just because somebody can do everything doesn’t mean that’s what they want to do.”

In the coming year, Lovette knows what she wants to do: address personal issues in her choreography. She has struggled with growing up in a poor and sheltered religious environment where she had daily Bible study sessions (she is no longer religious); with anxiety as a dancer; and, last year, with an assault outside of NYCB.

“I want to let out a lot of things that have happened in my life that aren’t necessarily sparkly,” she says. “I don’t want to hide the struggle.”

She hopes to pour those emotions into choreography by creating a work about the assault featuring Barton Cowperthwaite, her dancer-actor boyfriend. They met at an audition for Christopher Wheeldon’s musical An American in Paris; she was offered the role of Lise, but turned it down to focus on choreography.

As she becomes more established in that realm, do company members treat her differently? “People are a lot nicer to me now, but maybe it’s because I’m also being more open,” she says. “I’ve always been very introverted—I’m not usually the one who goes to parties. I think maybe they’re getting to know me more because I’m speaking out.”

She wavers for a moment and looks up with a wry expression. “But, yeah. People laugh at my jokes when they’re not funny.”

Photo by Jayme Thornton