6 LGBTQ+ Artists Who Work in Traditionally Binary Dance Forms—Ballet, Ballroom, Irish Dance—Share Their Experiences

“Is Adriana a lesbian? Because she looks like one.” Adriana Pierce was 21 years old and had recently joined Miami City Ballet when she heard secondhand that one of the male principals had asked another dancer that question. Though she had come out while a teenaged student at School of American Ballet and was, to her knowledge, the first woman to be openly queer while dancing with New York City Ballet, “that comment set off a huge breakdown for me,” she remembers. “I was constantly afraid that something about the way I danced would give me away to the audience. Women in ballet are supposed to be small and quiet and look like the rest. It was so destabilizing to leave the deepest, most beautiful parts of myself, the potential of myself as a whole individual, in this little shabby box outside of the studio.”

The dance industry is no stranger to queerness, or the diverse, overlapping populations whose sexual orientation, gender identity, or some combination thereof fall under the vast umbrella of the LGBTQ+ community. Contemporary dance, for example, has attracted many queer practitioners, offering spaces to experiment with gender roles and presentation in a natural extension of their lived experiences. But for queer dance artists who work within forms that are traditionally organized along the gender binary, like ballet, ballroom, and Irish dance, the friction between who they are and what the dance forms they love allow of them creates numerous challenges—regardless of whether they make the choice to come out, a deeply personal decision in which safety may be a major factor. That friction, however, also offers unique perspectives on how these spaces can become more welcoming to queer artists and audiences, in ways that contribute to the longevity and robustness of the art forms themselves.

Keeping Things Straight

Despite having grown up when queer representation in popular media was undergoing seismic shifts in quality and quantity, 25-year-old competitive ballroom dancer Katie Budenberg never encountered stories of women realizing they were lesbians in their early 20s, which was her experience. “I just didn’t realize I was in the closet,” she says. “I think dancing added to my beliefs that I was straight.” The London-based dancer had the same male dance partner throughout her childhood and recalls, “I was told nearly every week that we were going to grow up and fall in love and get married.” Add to that the strict gender divide traditionally inherent to the form: Followers are female, leaders male, and while a dearth in male-identifying partners might lead to two women being paired together, Budenberg has observed an attitude that “you dance with a woman until you’re good enough to get a man.”

That gendered divide is equally present in ballet and Irish dance training from the get-go. Hayden Moon, a Sydney-based transmasculine competitive Irish dancer, started out in ballet. He recalls feeling a profound disconnect between who he knew himself to be and how others perceived him as a preteen, when his ballet class began differentiating between girls’ and boys’ steps. “I remember having the understanding that everyone sees me as a girl and everyone tells me I’m a girl, so I must be a girl, and that’s why I can’t do the steps that the boy in the class is doing,” he says. Inside, he knew that wasn’t correct. Moon stopped dancing altogether in high school and only returned to Irish dancing during his undergraduate studies. At that point, he began finding queer community and came out as pansexual. In terms of gender, “I was very much overcompensating: playing a woman, not just in Irish but in my everyday life.”

The all-encompassing nature of training for aspiring dancers can heighten the pressure not to deviate from cisheteronormativity (social and cultural systems that privilege being cisgender—when a person’s gender identity corresponds to the gender they were assigned at birth—and heterosexual by treating them as the only normal form of gender identity and sexual orientation). Les Grands Ballets Canadiens demi-soloist Kiara DeNae Felder, 31, knew she wasn’t straight as a teenager, but, “I always was like, ‘We’re not going to think about that right now,’ ” they say. Felder, a nonbinary woman whose pronouns are she and they, came out as queer to her parents when she was 18 years old and in Pacific Northwest Ballet School’s Professional Division, but says she functionally went back into the closet, “out of a bit of fear, and being really one-track-minded. I felt like I had to put all my energy into ballet. And I think also, for me, as a Black person, I didn’t want to add another potential obstacle and have more reasons for someone to discriminate against me.”

In contrast, Emily Coles, 48, who danced recreationally from childhood but had no professional aspirations, feels her discovery of her queerness and decision to come out were entirely separate from dance. She realized she was interested in women as a teenager, began teaching ballroom professionally years later, and started competing on the same-sex ballroom circuit in 2009, after attending one such competition and being excited by how those dancers navigated ballroom’s gender roles.

Out, Proud, and Isolated

Until a rule change in September 2019 redefining a ballroom couple as “a leader and a follower without regard to the sex or gender of the dancer,” the National Dance Council of America—the official governing body for ballroom dancing in the U.S.—did not allow same-sex or gender-neutral couples at events it sanctioned. For dancers like Coles, who was only interested in dancing with another woman and last competed just before that rule change, that meant being shut out of the largest ballroom competitions in the country. Competitions expressly for same-sex couples—oftentimes explicitly geared toward queer dancers, such as April Follies or the dancesport category at the Gay Games—filled the gap for Coles, who has her own business as a ballroom instructor.

In the U.K., same-sex couples have long been allowed to compete in mainstream competition, and a July 2014 proposal for the British Dance Council to explicitly define a dance couple as “one man and one lady” was met with outrage. Still, Budenberg has noted that in her experiences in the mainstream national circuit, mixed couples are often treated more favorably: Mixed couples will get a warm-up while the All Ladies heat does not; All Ladies pairs are considered in a single heat, regardless of ability level, and face harsher cuts. “You have to be so much better if you are an All Lady partnership,” she says. “The only reasons I would want to dance with a boy again are because I’d get to dance so much more, be able to be trained by more people, get more respect at competitions, and be marked less unfairly.” But while she prefers to dance the follower role, she doesn’t feel comfortable with a male leader: “It feels so me to be on the floor with a woman,” she says. She and dance partner Alice Talleux (who is a straight woman) were the 2022 National Same Sex Ballroom Champions at the Inter Varsity Dance Championships, but have to fight at every competition “to not be treated as second best.”

In ballet performance, queer people generally have less visibility: While same-sex partnering and even gender-neutral casting have grown in prevalence in new, abstract works in recent years, the majority of narrative works—particularly full-lengths—hinge on heterosexual romance. For queer women and nonbinary dancers, that difference in visibility is more pronounced, and stretches into the studio. Pierce, who after her ballet career went on to perform on Broadway and in film and television, and currently works primarily as a choreographer, says that at Miami City Ballet, “it was me and the gay dudes and that was it. In some ways I felt so isolated from them as well as the straight dancers, because they don’t experience sexism.” She recalls being advised by a rehearsal director to wear more makeup in the studio if she wanted to get more parts, and feeling she had to look and dance like the other women in the company. In response, she “obsessively” sought validation of her sexuality outside of the studio, in ways she now acknowledges were not always healthy.

Milwaukee Ballet leading artist Annia Hidalgo stayed in the closet throughout her time with Ballet Nacional de Cuba. When she joined Milwaukee Ballet in 2012, she met Rachel Malehorn, then a company artist and the first openly queer woman Hidalgo had ever encountered in ballet. “I still was not out because I had a lot of fears, but meeting her gave me a lot of hope,” Hidalgo recalls. “This thing that I’ve been feeling for so long, it’s real; I’m not crazy.” The two began dating shortly thereafter and are now married.

It wasn’t until 2020, however, that Hidalgo met other dancers like her and her wife, when Pierce organized Zoom calls with queer ballet dancers of marginalized genders from around the world. “All of a sudden you have a bigger family that you never knew,” Hidalgo says. Many shared similar experiences from their careers and expressed that they, too, had thought they were the only ones.

Dancing as Yourself

Those meetings led Pierce to found #QueerTheBallet, an initiative seeking to increase the inclusion of LGBTQ+ voices and narratives in classical ballet (with a particular focus on queer women, transgender, and nonbinary dance artists) through producing new work, education, and community support. It was through #QueerTheBallet that Felder, who helped Pierce organize those Zoom meetings, had their first experience dancing a queer romantic pas de deux. Pierce’s Lay Your Love on Me, which Felder performed with New York City Ballet’s Miriam Miller at Fire Island Dance Festival last year, “felt a lot more vulnerable” than the straight roles she’s performed, “because I felt more pressure to make it authentic to who I am. There’s no male gaze involved.” Pierce describes choreographing for two women as “healing,” and particularly in the case of creating other duets for young, queer women, “I feel like I can give them something I never got to experience.”

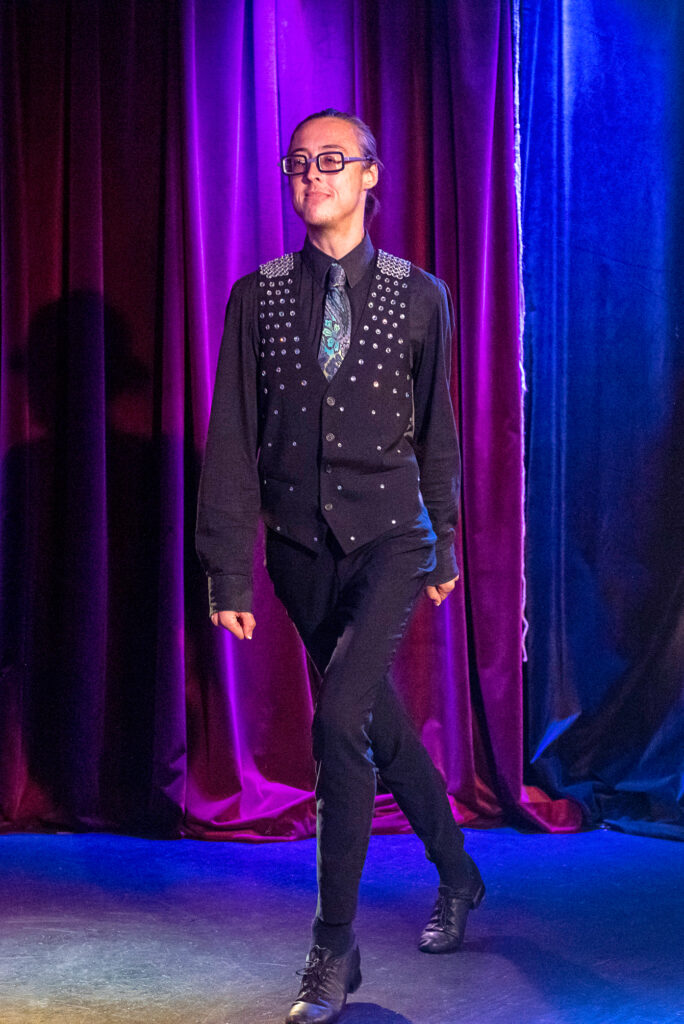

In the year between realizing he was transgender and coming out, Moon continued to compete in the women’s section at Irish dance competitions. “As much as I tried to pass it off, like, ‘You’re in drag, it’s just a performance,’ you can’t dance your best if you are hiding a huge part of who you are,” he says. After coming out as trans and formally beginning his gender transition in 2018, he had to change schools to find supportive teachers, but “I just felt this rush of gender euphoria the first time I put on the boys’ reel shoes.” It took the better part of a year for him to retrain his technique—women are expected to make very little noise and dance high on their toes when in soft shoe, while men’s steps are purposefully percussive, with a strong, aggressive energy. Moon and his supporters also had to fight for the Australian Irish Dancing Association to change official policy for him to be able to compete as his true gender identity. Now, “I’m doing the men’s steps, I’m wearing the men’s costumes, I’m being read as a man by everyone around me—and that makes me feel affirmed in my gender. I can focus on the steps and enjoy myself because I’m not having to pretend to be someone I’m not anymore.”

The impact of that visibility reaches beyond it being rewarding for the dancers who get to perform as themselves. Hidalgo had the opportunity to dance alongside her wife at Milwaukee Ballet in Rachel and Ania, a contemporary duet created for the pair by Dawn Springer, and last year, in Timothy O’Donnell’s The Kids Have Names, her role as a lesbian teenager included an onstage kiss. “It was amazing,” she says, “but the best part is people watching, knowing they are being represented. I never imagined seeing that as a kid. There are a lot of dancers out there that might be like, ‘Oh, it is possible.’ ”

Outside the Binary

While Moon has faced difficulties and discrimination as an out trans dancer, he acknowledges that one privilege he has is that he can dance as a man in the incredibly gendered Irish dance sphere without it causing him gender dysphoria. Gender is a spectrum, and artists whose gender identities don’t fall neatly on either side of a socially constructed binary face a more complex reckoning with where and how they fit within these art forms.

Differences in how nonbinary ballet dancers are trained due to their assigned gender at birth impacts their visibility and opportunities. Dancers who were assigned male at birth but are able to train on pointe and fit into the aesthetics of “female” ballet can step into those roles if they are in spaces that support them—think Ballet22, which invites male, mxn, nonbinary, and trans dancers to perform on pointe in their authentic gender identities, or nonbinary phenoms like Ashton Edwards or Maxfield Haynes. For nonbinary femme dancers like Felder (who arrived at their nonbinary identity during the pandemic shutdown), performing femininity is often treated as their default, rather than a choice, and “even if I’m doing double tours and double saut de basques, I probably won’t be able to lift my colleagues because I don’t have the training,” they say. “It’s a little bit harder for me to occupy a more masculine space in ballet.”

With young, male ballet students being rarer, it makes for steeper competition for dancers socialized as women. Meanwhile, their male counterparts often have more time and encouragement in the studio to develop in areas outside of their traditionally assigned roles in dance. Another possible reason for the relative invisibility of queer women and nonbinary ballet dancers who were trained and socialized as such: When the (often heterosexual) male gaze dominates choreographic creation and casting, it follows that a performance of female heteronormativity in the studio would be rewarded.

“It’s pretty stark, actually,” Felder observes. “Straight men take up a lot of space, gay men take up a lot of space, straight women take up a lot of space,” while queer women and nonbinary dancers rarely feel celebrated or have ballets created about their experiences. “You kind of just have to pretend to be a straight girl.” Nevertheless, Felder has found that “the more I stand in who I really am, the better understanding I have of my voice as a dancer. Understanding myself and my gender identity and my roots really helped make my dancing better.”

Budenberg and Moon both agree that at ballroom and Irish dance competitions, respectively, not much space is made for dancers outside the binary. “Even within those more queer competitions, it’s still women dancing with women; on the university circuit it’s called Same Sex—it’s still very much ‘boys and girls,’ ” Budenberg says, noting that she enjoys more acceptance because she naturally fits into the form’s high-femme aesthetic. Moon has been glad to see that there is now a non-gendered Mx. Pole Dance Australia section, a move towards inclusivity he would like to see expanded into other styles including Irish dancing.

The Work Ahead

Ballet, ballroom, and Irish dance have all made strides in terms of queer acceptance and inclusion. In mainstream ballet, it’s been 20 years since then–American Ballet Theatre star Marcelo Gomes appeared on the cover of The Advocate, which declared “Romeo Is Gay”; in 2021, ABT brought Christopher Rudd’s Touché into its mainstage repertory, its first such work with a same-sex kiss. The National Dance Council of America now allows same-sex and gender-neutral couples to compete at its ballroom events, while explicitly queer spaces—like Pink Jukebox in the U.K.—continue to flourish. In recent years, “Dancing with the Stars” and “Strictly Come Dancing” have featured same-sex pairings. In 2018, the Australian Irish Dancing Association not only revised its policies to allow dancers to compete as their authentic gender identities, but also added a section to its code of conduct stipulating inclusion and respect for all competitors regardless of LGBTQ+ status.

There is, nevertheless, work to be done, and it starts at the studio level. The simplest change is looking at the language used in technique classes. In ballet, that means rather than differentiating between ladies and men, instead referencing who is on pointe and who isn’t, or, in pas de deux work, who is leading and who is following—an adaptation that has already begun to be implemented in ballroom and other social dance styles. Coles reminds her ballroom students that “there is a leader and there is a follower. Some people enjoy one more than the other, and it is not related to your gender or sexual orientation—these are the roles on this team.”

Hidalgo, who also teaches ballet classes, believes it can only benefit all of the dancers in the room to learn all of the steps, regardless of gender; rather than sectioning off pointework as inherently female and bravura turns and jumps as inherently male, those aspects of technique can instead be treated as tools that anyone who is interested can learn to use. (Ballez founder Katy Pyle offers a model for reclaiming ballet technique that should not be overlooked, but mainstream organizations have been slow to follow suit.) Moon has noticed a trend of Irish dancers in the men’s section beginning to integrate pointework, a softening of the rigid gendered technical divide in pursuit of virtuosity.

Schools that are committed to being welcoming to queer dancers can also take the initiative to make that clear to prospective students. “All you have to do is put the queer flag and the trans flag at the bottom of your website and say, ‘This is a school that is inclusive to all dancers,’ ” Moon says. An easy-to-find declaration takes the onus off of queer students to out themselves to learn if they will be safe in that space, or to attend a trial class without knowing one way or the other—potentially placing themselves in a harmful situation. Moon adds that LGBTQ+ inclusivity training is something he believes should be compulsory for dance teachers.

At the professional level, attention to inclusive language should expand to what is used on audition notices, schedules, and casting sheets; look at alternatives to “ladies and men,” perhaps ones that focus on function over gender. “You might not have a nonbinary or queer dancer in the company,” Pierce says, “but if you open up the language, you create the possibility for people to feel safe.”

Expanding representation onstage requires attention to how we get it there behind the scenes. Pierce wants to see ballet repertories expand to include queer narrative works that can be folded into the canon—a challenge she firmly believes ballet can withstand—which starts with where companies invest their budgets when commissioning new works. To that end, Felder wants to see more queers, femmes, and people of color in leadership roles: “There needs to be more of an influence that’s not just taking over the same dynamics that have always been.”

Ultimately, queer dancers work within these traditionally binary forms out of a deep love for them. They advocate for not just tolerance but inclusivity and acceptance because of a belief that these parts of the dance world can grow, expand, and evolve to hold them in all of their queerness, without compromising the art’s core. Budenberg, Moon, and Pierce, who are each highly visible on social media, regularly receive messages from queer people all over the world—some are dancers who find encouragement and community in their work, while others are nondancers who have an interest in the art form but have previously never felt there was a place in it for them. “Facilitating community has been the most rewarding and beautiful part of this,” Pierce says, “because I know what it was like not to have it.”