Searching for Dance History’s Queer Women? Start Here

In the November 2023 issue of Dance Magazine, dancer and educator Samm Wesler asks: Where are dance history’s queer women? Here’s a response from dance artist, educator, and former Dance Magazine editor in chief Wendy Perron.

It’s true: Lesbians in dance history have not been as visible as gay men. It hasn’t been as open a secret as with the male dancers you name. In our field, gay men are more prevalent and more accepted—it beats me which came first.

As a dancer who identified as a lesbian for a five-year chunk of my past life, I’ve watched how attitudes have changed. Sara Wolf wrote in a 2003 article titled “Lesbian Choreographers Redefine Motion” that “prior to Stonewall, the cutting-edge downtown dance scene was not open or hospitable to lesbians.” But even after Stonewall, it took women longer than men to come out.

In 2011, dancer-choreographer Pat Catterson wrote an essay in Attitude titled “Can You Tell I Am a Lesbian When I Dance?” She basically spent the first 30 years as a dance artist hiding her identity. “I wanted to stay in the closet professionally,” she wrote. “I didn’t think it would be advantageous to my career to talk about it. . . . Partly it is that we choose to be invisible. Gay men in dance do not. Visibility is possibly more of a liability for us.”

Maybe it’s just a matter of numbers—that a certain mass is necessary before there can be a sense of community. It seems that queer women dancers tend to be isolated, whereas gay men dancers are part of a social swirl.

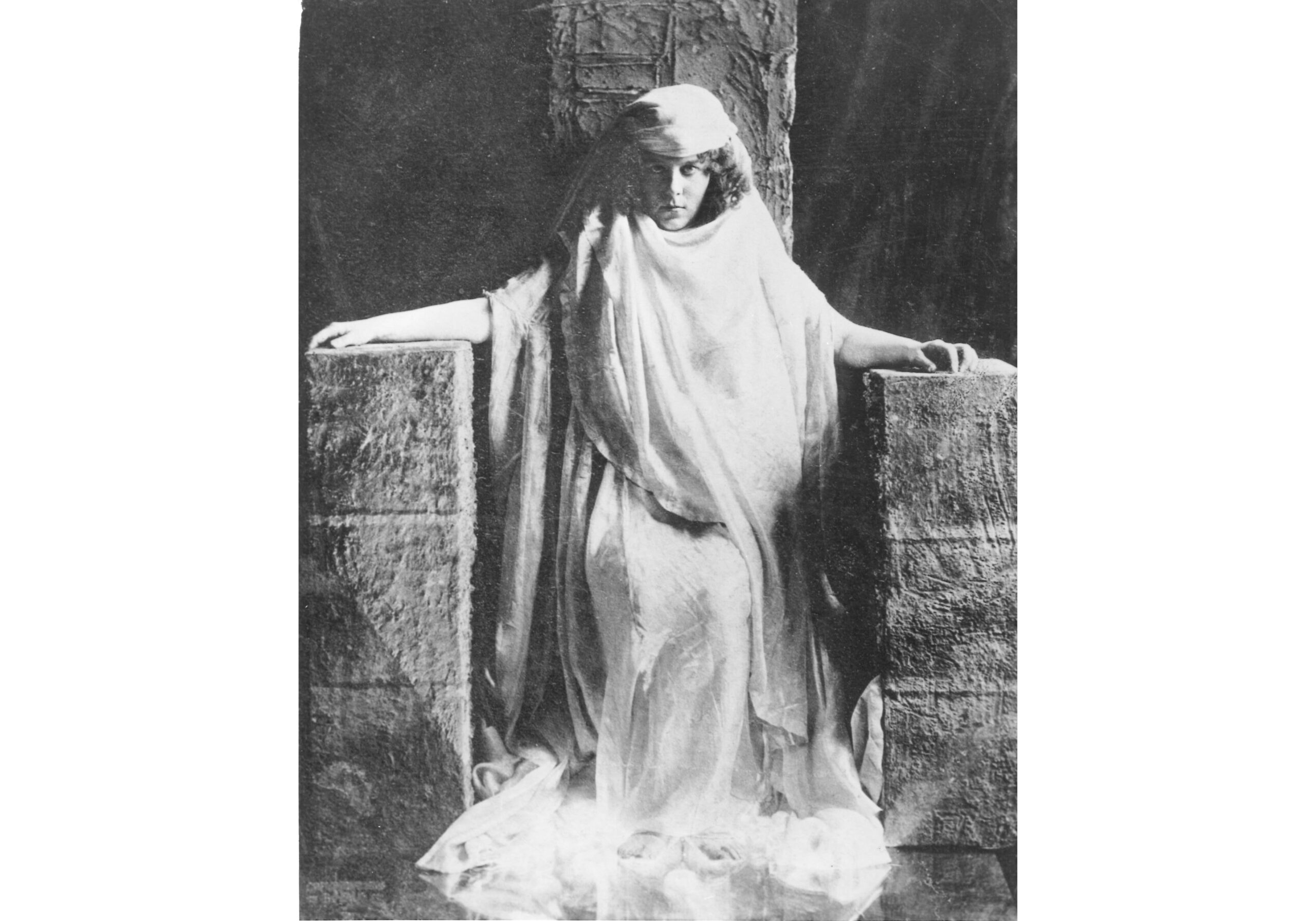

Your question was about queer women in dance history, so let’s go back. The American Loie Fuller, slightly older than Isadora Duncan, took Paris by storm in the 1890s, not by exhibiting her body, but by covering up her body with fantastic imagery—a lily, a butterfly, a flame. Considered one of the mothers of modern dance, she invented lighting devices that, along with yards and yards of silk, created these images as a stunning theatrical coup. She had a long-term relationship with a woman; in Dancing Women: Female Bodies On Stage, Sally Banes describes La Loïe as an openly identifying lesbian. (For a deeper dive into Fuller’s sexuality and the surrounding homophobia, see Ann Cooper Albright’s book Traces of Light: Absence and Presence in the Work of Loïe Fuller.)

Jill Johnston, the renegade Village Voice dance critic of the Sixties, was out, very far out. Her collection of dance reviews, titled Marmalade Me, is essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the rebellious Judson Dance Theater. Staging her own rebellion, around the same time as the Stonewall Riots, she shifted from writing dance reviews to writing essays about queer women, which were gathered in her 1973 book, Lesbian Nation: The Feminist Solution. (We’ll all be able to read more of her writing next year, when Duke University Press will publish a new collection of Johnston’s writings—edited by Clare Croft, whom you mentioned.)

The Wallflower Order Dance Collective, a feminist troupe formed in 1975, morphed into the Dance Brigade a decade later. They are a mix of gay and straight women in San Francisco’s Mission District. Co-founder Krissy Keefer is quoted as saying, in this 2011 article by Keith Hennessy, that they were probably the first dance company “to express explicit lesbian sensibilities and concerns.”

The feminist Seventies brought out Pat Graney, a Seattle choreographer devoted to social justice issues. She is out and dedicated to supporting the lesbian community. She mentored many dancers, including Gina Gibney, the choreographer and entrepreneur who created the Gibney spaces that have done so much for the New York City dance community. In 2016, Out magazine named Gina Gibney one of its OUT100.

In the 1980s, things started getting more interesting. A group of downtown Manhattan dancers including Lucy Sexton, Jennifer Monson, and Jennifer Miller were gloriously frank about their sexuality. I remember, in the mid-1980s, Johanna Boyce’s Ties That Bind, featuring a beautiful duet in which Miller and Susan Seizer talked openly about their relationship in a funny, poignant way. Decades later, in 2007, at a Movement Research gala honoring Yvonne Rainer at Judson Memorial Church, Monson and DD Dorvillier suddenly dashed to the altar for an impromptu, outrageously caressing makeout session. That was just the tip of the iceberg of Monson and Dorvillier’s long, wild ride as rambunctiously out lesbian dancemakers.

(A side note: You also asked, “Why, when I learned about Yvonne Rainer, was her sexuality never mentioned?” The reason is probably that she was in heterosexual relationships during the time she was making history with her ground-breaking danceworks of the Sixties. It was only around 1990, while making feminist films, that she developed a relationship with another woman.)

I think the new acceptance of lesbian artists is partly due to the shift from modern dance to postmodern: Choreographers in the latter mode tend to be less gendered. While the portrayal of women in Graham, Limón, and Ailey was always fairly traditional, the gender presentation of postmodern choreographers like Trisha Brown, Bill T. Jones, Mark Morris, and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar are less gendered (or, rather, multi-gendered), therefore more likely to attract gay women. Not only is the presentation of women less femmy in postmodern dance, but there’s less dramatic tension between men and women. I think this is also true in current versions of tap and flamenco.

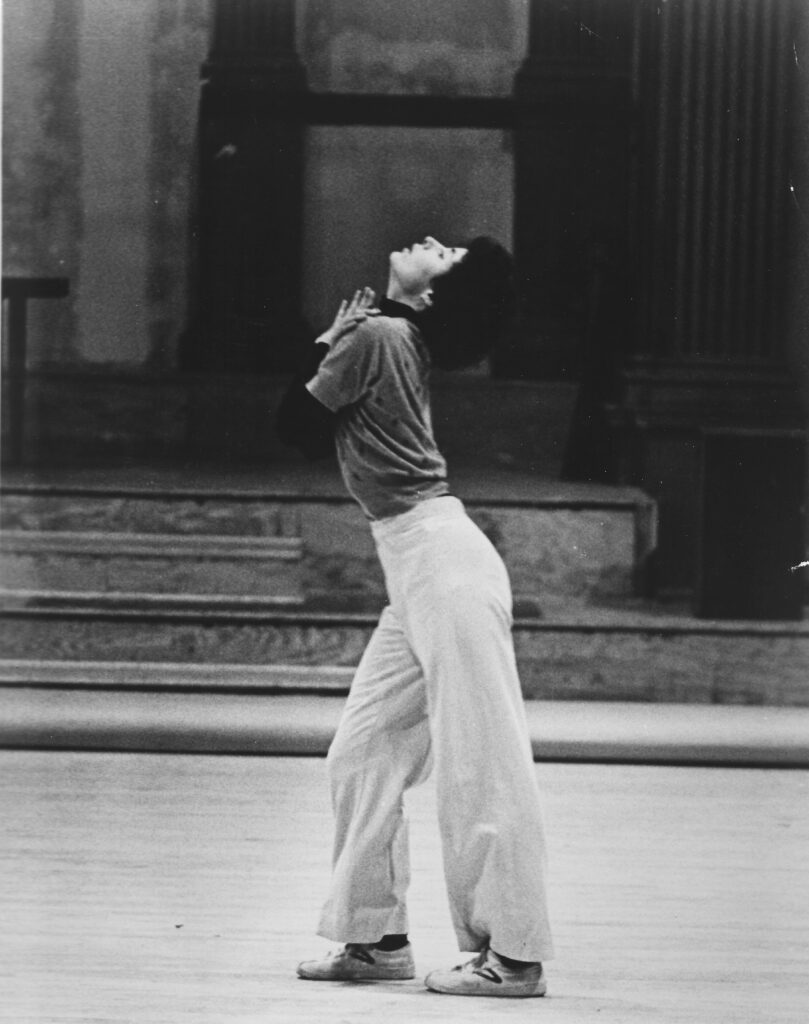

In her 2003 article, Wolf contends that lesbian dancemakers “re-conceptualize the female body in motion.” Case in point: Elizabeth Streb, whose slam-bam athletics transcend gender expectations. “When you’re out of that box, it allows you to break out in other ways, make different choices, ask other questions,” Streb told Wolf. “You’re much more able to discard the tools that have already been invented.”