This Voguer Is Bringing the Underground Ballroom Community to the Epitome of Uptown Culture: The Guggenheim

As a 6-year-old in Senegal, Omari Wiles began training in the family business: dance. His parents started the Maimouna Keita School of African Dance, and after the family moved to the U.S., Wiles participated as a performer and then assistant director.

As a teenager, he was introduced to New York City’s ballroom scene—the community of LGBTQ chosen families that congregate for dance- and fashion-centric competitions. That lively world was famously depicted in Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, which captured the creativity, warmth and challenges that the mostly black and Latino gay men and trans women faced, sometimes to tragic ends.

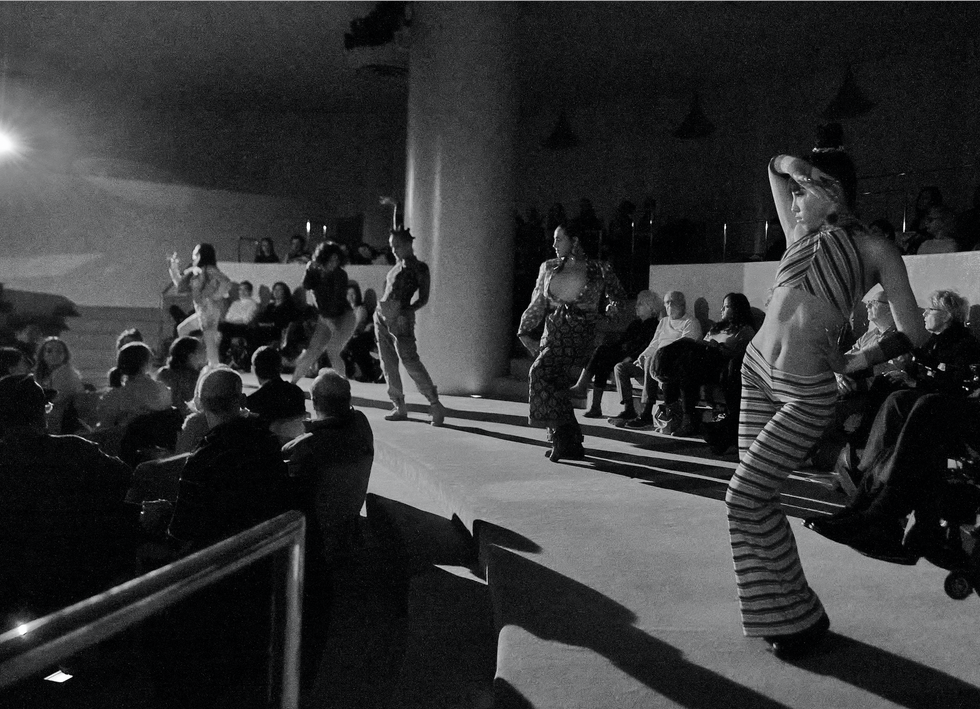

Wiles, named one of Dance Magazine‘s “25 to Watch” in 2017 for his infectious performances with Ephrat Asherie Dance, founded Les Ballet Afrik last year to present his bespoke mix of house and voguing styles with African dance. The Guggenheim Museum’s Works & Process series soon commissioned New York is Burning, an homage to Livingston’s film and an addendum to it. Les Ballet Afrik offered a preview in January, before the pandemic pushed the work’s official premiere to the fall.

What did your parents teach you about movement and performance that’s still with you?

It’s all about the connection. In African dance and culture, the musicians are so connected with the dancers in terms of the timing, in terms of call and response, in terms of the energy that they share with each other. When I’m creating movement, it has to have an attachment to the music, and it has to have an emotional attachment. That’s going to help the audiences connect to the percussion of the body.

How did you come to the ballroom scene?

It was hard for me to express my feminine side in the African community because everything was so hypermasculine. There was a fight within myself about sexuality. In high school, I was introduced to a group of friends who were already in ballroom. I was amazed to see black and Latino men express themselves in a feminine way and a very fashion-forward, very colorful, vibrant way.

New York is Burning Robert Altman, Courtesy Works & Process

When did you begin to bring together voguing and African dance?

African dance has always been in my body. For a lot of the black bodies in ballroom, I felt like they had a disconnect to a lot of their heritage. So, I felt like a way for me to bring that awareness was to continue to vogue like an African dancer, but still embrace the feminine side of ballroom and what vogue allows you to express.

When did you first see the film Paris Is Burning?

Back in 2005, about a year after I was introduced to the ballroom scene. I wanted to learn the history of ballroom, so Paris Is Burning really helped me get a sense about why they created it and the struggles that they faced.

With your new work, New York is Burning, how do you pay homage to the film and also add your own story?

I definitely wanted to bring back all the sounds and costumes and flair from the 1970s and ’80s. In this work, there are a lot of African and Latin movements that I’m fusing with vogue and the house style. This goes back to not seeing enough representation of those cultures in the ball scene. Ballroom is deeply rooted in African and Latin culture, even if a lot of the categories are based on European standards of beauty. We’re trying to get away from those oppressions! Why not follow the traditions of our ancestry?

What does it mean to you to bring this work about a historically underground and underrepresented community to the Guggenheim, the epitome of uptown culture?

The company is only a year old, so for us to have reached the Guggenheim within a year, it’s a big responsibility. And it means so much to get to represent my community on a different platform than the box that society is always putting us in. I want to bring into the Guggenheim a clean and clear representation of this community with people who are invested. It’s not just a bunch of dancers doing a bunch of counts.

What opportunities does it offer?

Hopefully this piece also inspires the Guggenheim crowd to get out there and explore themselves through fashion, through sexuality, through gestures, such as being masculine or feminine. What are those lines? What are those walls? I want them to question and see the way that they live. What struggles have they gone through to get to where they are now? That’s really important too.