The 4 Rules That Will Get You Through Your First Contact Improv Class

Experienced practitioners of contact improvisation appear to float through the air and move through the most daring positions with ease. Those new to the form, on the other hand, often feel awkward and impatient. Some dancers hesitate, worried they will hurt their partner by giving them too much weight. Others move too quickly, trying for impressive lifts without laying the proper groundwork. Having spent so much of their training focused on aesthetics, many dancers struggle to stop fixating on what their movement looks like. But just like any other form of dance, contact improvisation skills can be developed with practice and the right approach.

1. Forget Your Assumptions

Contact improvisation was created to be done by anyone, regardless of dance experience. While dancers have certain advantages, like familiarity with movement and partnering, they also face specific challenges.

“Some students may be familiar with partnering techniques where the places people touch and the ways they lift are very composed,” says Stephanie Nugent, who teaches contact at Indiana University. “Other people may have improvised, but not with partnering.” Dancers may have also learned that men should lift women, that bigger people should lift smaller people, or that one person should be in charge. None of those things are considered a given in contact improvisation.

Rather than thinking of picking a partner up and putting them down, says Barnard College professor Colleen Thomas, dancers should focus on the connection from the floor, to their core, to their partner.

2. Know When to Say No

Part of contact improvisation is learning to say yes to your own ideas and your partner’s. It may seem counterintuitive, but one trick that can help you feel more comfortable saying yes is knowing when and how to say no.

“Touch has so much social and physical meaning. It’s important to acknowledge when you feel uncomfortable, and then make a choice either to be interested in that or say ‘I want to stop,’ ” says Nugent. “Being able to say no is really fundamental to safety.” Thomas suggests taking a moment to pause and reset if you begin to feel uncomfortable.

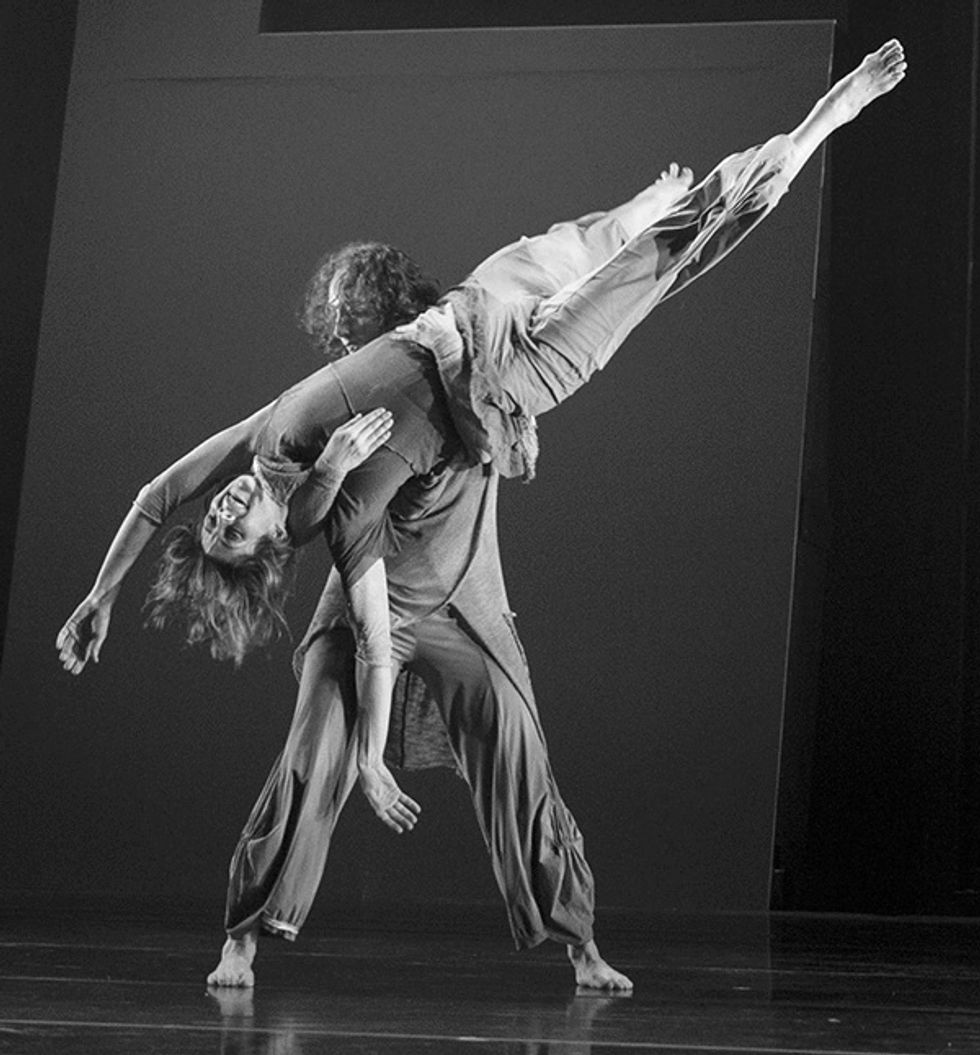

For Nugent, saying no is fundamental to safety. PC Crow’s Eye Photography, Courtesy Nugent

To get students more accustomed to touch, most teachers begin with simple exercises like placing hands on a partner, starting with neutral places like the shoulders. “Through my contact practice, I’ve learned to recognize my own boundaries, whether physical or emotional,” says Nugent. “It’s really powerful to have that awareness and make conscious choices based on it inside and outside of the studio.”

3. Be Okay With Not Knowing

As with other forms of improvisation, part of contact is learning to notice your own impulses without judging them. However, the addition of a partner can complicate efforts to go with the flow. “Dancers have a harder time getting out of their choreographing mind. They want to make a lift happen, or try to control their partner,” says Thomas. “But in contact there is shared weight. You would fall if your partner left and vice versa. There are no followers. Everyone is a leader.”

Instead of thinking about what the dance might look like, focus on your sense of touch. Feel the connection between your body and your partner’s, and work on maintaining a point of contact as you move through space.

Colleen Thomas emphasizes that everyone is a leader in contact improv. PC Alex Escalante, Courtesy Thomas

Thomas feels that the freedom of contact is especially beneficial for her college students, who are striving to succeed in a high-pressure environment. “This is the one time during their day that they get to come in and not know,” she says. “It really opens up new pathways in the body.”

4. Think About Quality

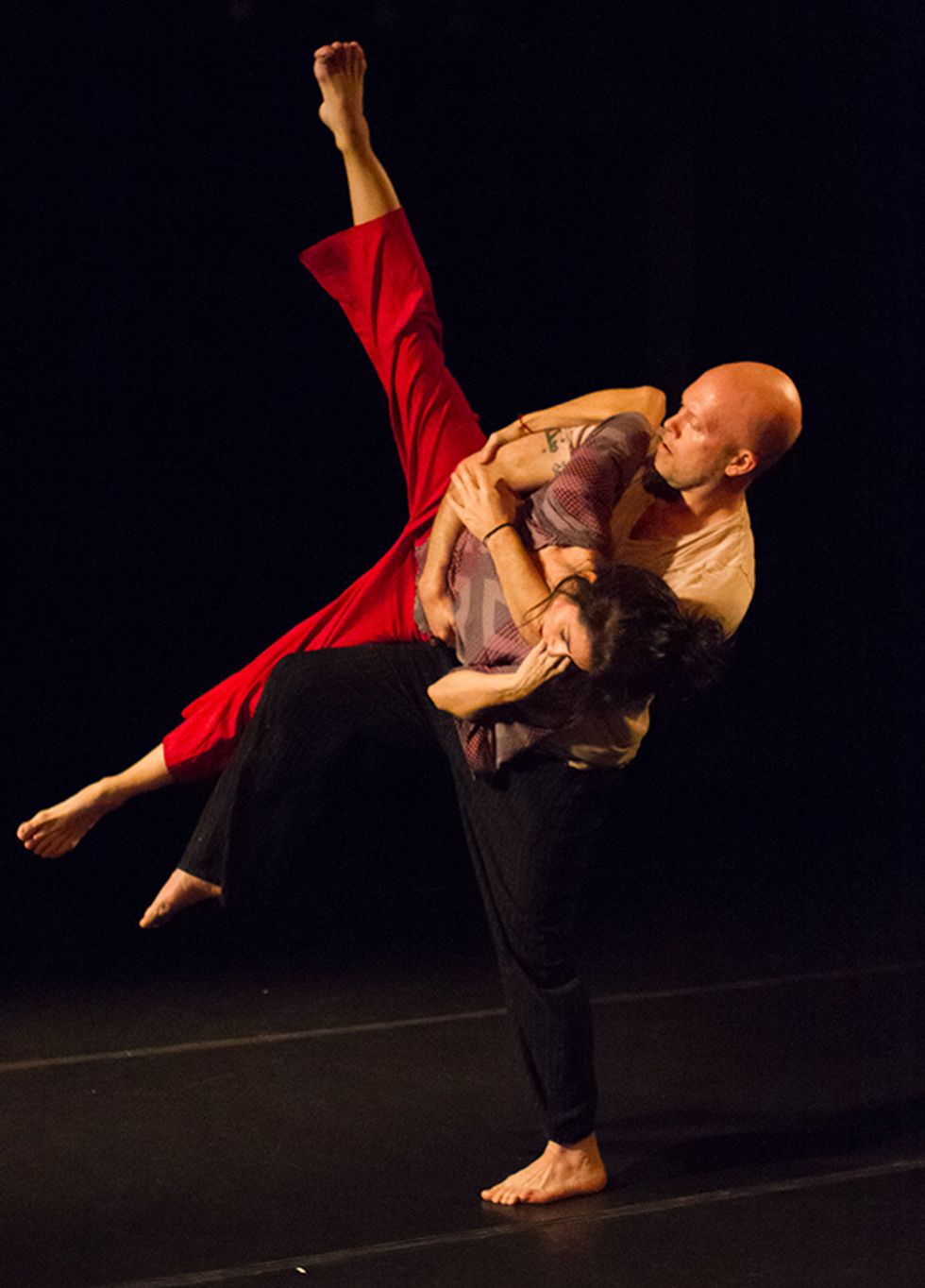

Dancer Christina Robson has worked with several choreographers who rely on contact improvisation for movement generation, including Bill T. Jones, David Dorfman and Alexandra Beller. Robson’s biggest aha moment came when she started to think not just about giving weight to her partner, but about whether she was being active or passive in that exchange. “I realized that surrendering into softness or engaging into active tone creates different transitions into and out of my partner or the floor,” she says. Focus on the quality of your touch. Is it firm or light? Are you pushing or softening into your partner? Experimenting with different intentions will change the trajectory of the dance.

Christina Robson (in white) in Bill T. Jones’ Analogy: A Triology. PC Ben McKeown, Courtesy NYLA

After years of practice, Robson says she still has to remind herself to be patient and listen to her partner. According to Thomas, honing those physical listening skills will benefit your dancing beyond contact. “What’s happening in the brain in contact is similar to what’s happening when we meditate,” she says. “You learn how to take care of yourself, and trust, and take risks, and it creates a lot more range in your dancing.”